As the U.S. presidential election in November approaches and the campaigns of former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris ramp up, hackers are intensifying efforts to disrupt or influence the vote. Among these adversaries, Iran is emerging as an increasingly significant player.

Three U.S. agencies, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) warned in a recent joint statement that Iranian state actors have stepped up their efforts to interfere in this year’s election by perpetrating disinformation and launching cyberattacks.

“We have observed increasingly aggressive Iranian activity during this election cycle, specifically involving operations targeting the American public, and cyber operations targeting Presidential campaigns. This includes the recently reported activities to compromise former President Trump’s campaign, which the IC (Intelligence Community) attributes to Iran. The IC is confident that the Iranians have through social engineering and other efforts sought access to individuals with direct access to the Presidential campaigns of both political parties. Such activity, including thefts and disclosures, are intended to influence the U.S. election process.”

They are not the only ones raising concerns. Over the past two months, intelligence officials – along with eminent cyber threat researchers – have presented growing evidence of Iran’s hacking activities. As our analysts have previously noted, Iran’s attempts to meddle in U.S. elections are not new: hackers associated with Iranian security services are now almost on par with Russia’s and China’s information operations game and have been targeting presidential and midterm elections since at least 2018 (in 2021, for instance, the U.S. Justice Department charged two Iranian hackers with election interference for posing as Trump supporters and sending threatening emails to Democrats).

However, U.S. agencies emphasize that “Iran views this year’s elections as particularly critical to its national security interests, which has heightened Tehran’s motivation to influence the outcome.” The agencies also noted, “We have seen increasingly aggressive Iranian actions during this election cycle.”

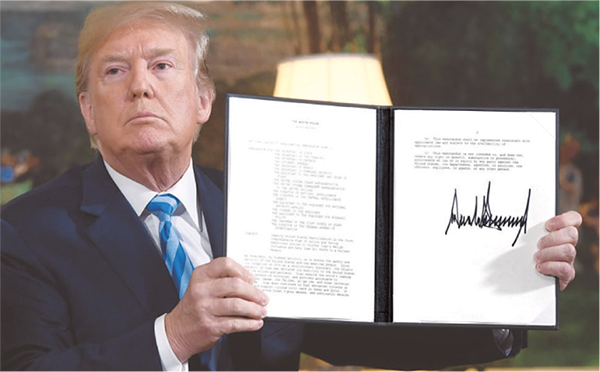

Former President Trump and his allies have been frequent targets of Iranian hacking efforts, and, according to intelligence officials, attempts to breach their email accounts might be linked to efforts to assassinate U.S. officials in retaliation for the 2020 killing of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani during Trump’s presidency.

The agencies in question have formally accused Iran of carrying out a hack-and-leak operation, targeting Trump’s campaign, which the Trump campaign team disclosed earlier this month. These tactics, reminiscent of Russia’s breach of the Democratic National Committee during the 2016 election, are just one aspect of Iran’s broader election interference strategy, which also includes disinformation campaigns designed to create division among U.S. voters.

Iran is not the only adversary causing concern in Washington. Russia’s election interference efforts have been well-documented, and U.S. officials have increasingly sounded the alarm about China’s shift from cyber espionage to more disinformation and disruption campaigns. Russia and China remain the primary threats, however, largely due to their more advanced and sophisticated capabilities.

Russia and China operate in a league of their own, experts note. It could be argued that analysts often underestimate countries like Iran and North Korea, but incidents like the Sony hack or the recent Trump campaign breach show that even with less sophisticated skills, they can find and exploit vulnerabilities.

Any nation with a vested interest in the outcome of a U.S. presidential election will explore ways to influence it: while Russia and China are often seen as the most hostile and capable, other nations across the globe have a perceived stake in the election results, making it crucial to consider threats from all directions.

OpenAI has recently shut down a cluster of ChatGPT accounts that were being used in an Iranian influence campaign targeting American users. Researchers identified this campaign – dubbed “Storm-2035” – earlier this summer. It primarily focused on topics like the Gaza conflict, Israel’s participation in the Olympic Games, and the U.S. presidential election, but it has only garnered minimal engagement on social media.

The campaign utilized ChatGPT in two main ways: generating long-form articles and creating shorter social media comments. The first approach involved producing articles on U.S. politics and global events, which were then published on five websites masquerading as either progressive or conservative news outlets. The second approach involved creating short comments in both English and Spanish, which were posted on social media platforms. Researchers identified a dozen accounts on X and one on Instagram as part of this operation, some progressive, and others conservative. These accounts generated some of their content by asking ChatGPT models to rewrite comments posted by other social media users.

Meanwhile, the Iranian threat actor APT42 has been focusing on U.S. presidential campaigns, targeting both campaigns with spearphishing attacks. In May and June, APT42 targets included the personal email accounts of roughly a dozen individuals affiliated with Biden and Trump, including current and former officials in the U.S. government and individuals associated with the respective campaigns. There were numerous APT42 attempts to log in to the personal email accounts of targeted individuals. The group has also escalated its phishing attacks against users in Israel, targeting people with connections to the Israeli military and defense sector, as well as diplomats, academics, and NGOs.

Researchers have recently published details on the aforementioned Iranian campaigns targeting presidential election teams. According to the reports, Mint Sandstorm, a threat actor attributed to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) sent a spear-phishing email to a high-ranking official of a presidential campaign from a compromised email account of a former senior advisor. The same group also unsuccessfully attempted to log into an account belonging to a former presidential candidate. Additionally, Peach Sandstorm – another group tied to the IRGC – compromised a low-level user account at a county government in a swing state.

Meanwhile, the Trump campaign disclosed that some of its internal communications had been hacked by “foreign sources hostile to the United States”, and data was shared with the center-left news website POLITICO (which stated it received the hacked information from an anonymous AOL email address). In the past, old anonymous AOL addresses were mostly used by Russian actors.

The U.S. government has repeatedly accused Russia of election interference, which researchers dubbed “Doppelganger”. The U.S. Justice Department seized thirty-two domains that were allegedly being used to covertly spread Russian government propaganda with the aim of reducing international support for Ukraine, bolstering pro-Russian policies and interests, and influencing voters in U.S. and foreign elections, including the upcoming election. The U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has sanctioned ten individuals and two entities for their alleged involvement in a scheme to covertly recruit unwitting American influencers in support of their malign influence campaign, and the U.S. State Department has also announced a $10 million reward for information on foreign interference in US elections.

In addition to the above, four of the Five Eyes counties, have recently issued a joint advisory on Cadet Blizzard, a threat actor attributed to the Russian GRU’s Unit 29155. The threat actors appear to be gaining cyber experience and enhancing their technical skills, relying on cooperation from known cyber-criminals and privateers to conduct their operations. According to the advisory, Unit 29155 cyber actors have conducted computer network operations against numerous NATO members, as well as many other countries in Europe, Latin America, Central Asia (and of course, Ukraine). The activity includes website defacements, infrastructure scanning, data exfiltration, and data leak operations, with the actors selling or publicly releasing exfiltrated victim data. Since early 2022, the primary focus of the cyber actors appears to be targeting and disrupting efforts to provide aid to Ukraine.

Russia is arguably leaning heavily into conspiracy theories (including the two Trump assassination attempts) but officials and experts have stated that Russia is primarily attempting to sow domestic discord and discredit the democratic process, with no clear preference for either candidate in their efforts.

In 2018, during his previous term in office, President Trump unilaterally abandoned the 2015 nuclear accord that Tehran had signed with world powers and imposed waves of sanctions on the Islamic Republic, putting its economy under severe pressure. Iran’s long-term strategy is the removal of U.S. influence from the Middle East, where Tehran intends to become the dominant power. To be able to fulfill this role, the Iranian regime does not want to deal with another Trump administration.

Iran is among world leaders in terms of using cyber warfare as a tool of statecraft. Iranian hackers have been repeatedly successful in gaining access to emails from an array of targets, including government staff members in the Middle East and the US, militaries, telecommunications companies, and critical infrastructure operators. The malware used to infiltrate the computers is increasingly more sophisticated and is often able to map out the networks the hackers had broken into, providing Iran with a blueprint of the underlying cyberinfrastructure that could prove helpful for planning and executing future attacks.

Moreover, Iran is now supplementing its traditional cyberattacks with a new playbook, leveraging cyber-enabled influence operations (IO) to achieve its geopolitical aims. Iran is likely trying to tap into Chinese and Russian expertise in “soft war”, which is an Iranian doctrinal term that refers to the use of nonmilitary means (such as economic and psychological pressure and information operations) to erode regime legitimacy, cultivate domestic opposition, and, propagate Western values in Iran.

Arguably the most concerning part about AI is its ability to amplify disinformation at an exponential rate. In 2016, Russian operatives often had to create and elevate false narratives, but now they can increasingly simply amplify the extreme statements made by Americans themselves using AI. While foreign adversaries aren’t the source of the discord in American society, they can effectively exploit the pre-existing social divisions, and with a more radicalized population willing to believe in divisive narratives, foreign actors have more opportunities to influence the election’s outcome.

A U.S. intelligence official noted that foreign actors, especially those from Russia, are becoming more “professional”, even working with marketing and PR firms to shape public opinion through fake websites and campaigns. However, as Western authorities are catching up, these influence tactics are becoming more refined.

Beyond disinformation campaigns, there’s the potential for direct interference, such as hacking voting machines. While experts can’t rule out this possibility, it is not considered to be an acute risk with the greater concern being an influence campaign that undermines trust in the election results. The most troubling scenario would be a combination of perceived interference and an influence operation that falsely suggests a major hack impacted the outcome. These campaigns are parasitic, feeding off the divisions already present in society: the more toxic the environment, the more opportunities they have to exploit.

Iran’s heightened cyber activity and bolder approach may also be driven by the ongoing conflict in the Middle East, particularly between U.S. ally Israel and Iranian-backed groups like Hamas and Hezbollah. The overlap of regional tensions with Israel and the U.S. election timeline has prompted Iran to step up attacks on high-profile targets, drawing significant attention to their efforts.

Iran is attempting to influence the election, using fake online personas and troll farms to spread disinformation aimed at undermining Trump’s chances for re-election while also looking for an opening in Trump’s team cybersecurity that could gain Tehran access to information, which could be subsequently used to discredit candidate Trump in his election efforts.

Iran’s main focus remains on preventing Donald Trump from re-taking office since Iranian officials appear sure a Republican administration would be more politically hostile to them and their regional proxies and interests.

The Trump administration’s withdrawal from the 2015 Iran nuclear deal three years after its signing by a previous Democratic administration triggered escalating tensions in the Middle East, culminating in the January 2020 U.S. drone strike that killed Qassem Suleimani, commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force, followed by retaliatory Iranian strikes.

Since the outbreak of war with Hamas last October, Iran has also worked to deepen rifts in the U.S.-Israeli relationship, trying hard to undermine the backing Tel Aviv – Tehran’s primary adversary – receives from Washington.

Looking forward, we can thus expect Iranian actors to employ all forms of statecraft, including cyberattacks against American institutions while simultaneously intensifying their efforts to sow internal divisions within the U.S., driving the attention of the electorate and politicians inward. These campaigns are likely going to be centered around amplifying existing divisive issues, like racial tensions, economic disparities, and gender-related issues.

Russia has inherited the rich Soviet legacy of information operations and put it to early use by pioneering the instrumentalization of social media for large-scale high-efficiency influence operations around the globe. As we have noted in a recent report, Russia has a highly developed lexicon for hybrid warfare and applies it systematically across all potential weapons, be that information, psychological operations, or acts of physical sabotage. It now appears that even sections of military intelligence like Unit 29155 which were previously known mainly for physical tactics, including poisonings, attempted coups, and bombings inside Western countries are also increasingly moving their activities into the fifth domain as the global economy goes increasingly online. We have also previously warned that Russia will likely increasingly use privateers in its operations. This trend will only continue and every large organization should take preventive measures, in expectation of an increasingly dangerous online environment.