Taiwan holds a presidential election on Jan. 13, and the year could start with a small crisis in the straits. Current Taiwanese Vice President Lai Ching-te, who serves under President Tsai Ing-wen and is a member of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), holds a narrow lead in the polls. His election would ire Beijing; he is an advocate for a more independent Taiwan and strongly opposed to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Although Lai has said he won’t call for formal Taiwanese independence or drop the Republic of China name – a red line for Beijing – he has also said that Taiwan’s sovereignty is “a fact”. A Lai victory would likely prompt aggressive moves from Beijing, including naval maneuvers, airspace intrusions and cyber attacks. President Xi’s remarks to U.S. President Joe Biden about reunification with Taiwan when they met in November stirred some panic – a Lai victory might indeed be just enough to trigger massive overreaction from Beijing. While straight invasion is not very likely, it cannot be ruled out either, while massive diplomatic fallout and cyber repercussions are almost given.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, many Taiwanese were forced to grapple more seriously with a longstanding fear of their own: What if China invades Taiwan?

After Mao Zedong’s Communist Party seized power on the mainland in 1949, exiled Chinese nationalists led by Chiang Kai-shek established an enclave on the island of Taiwan. In opposition to its opponents in Beijing, Chiang proclaimed the government in Taiwan, officially known as the Republic of China, to be the sole legal government of China. At first, a large portion of the West, including the United States, agreed. In the Cold War, the Taiwanese government in Taipei emerged as a crucial ally of the United States and took over China’s seat on the UN Security Council.

However, all changed in 1979 when the US moved its recognition from Taipei to Beijing, following years of diplomatic efforts that started with US President Richard Nixon’s historic 1972 visit to China. Washington adopted a strategy of strategic ambiguity towards Taiwan with this adjustment, and it still does. Washington recognizes Beijing’s belief that Taiwan is a part of China under the “one China” theory, even if Beijing does not publicly adopt this view. Although it only officially acknowledges the People’s Republic of China, the US maintains close connections to Taiwan and has emerged as the country’s de facto security guarantor. The United States, however, is invested in the status quo – Washington would be opposed to both Taiwan declaring independence and to a Chinese attack on the island.

Future Taiwan is a hot spot for increased Sino-American rivalry. China wants to reunite with Taiwan because it sees it as a colony gone wild. These days, there is some degree of relationship between the two regions, and they also depend on each other economically. However, Beijing regularly threatens Taipei with heightened military drills in the Taiwan Strait in recent years. When Beijing feels that the “one China” principle has been violated, as it did in 2022, when Nancy Pelosi, the then-U.S. Speaker of the House of Representatives, became the first senior official to visit Taiwan in 25 years, the Chinese capital usually reacts with a show of force.

Regarding how to settle the political status of their island, Taiwanese people are divided. Many were originally drawn to the idea of eventually unifying with China, but the increase in authoritarianism on the mainland has put them off. Some Taiwanese believe that the idea of “one country, two systems” is absurd, as seen by the outcome of Hong Kong, where Beijing crushed and subdued the local democracy. Even though 90% of Taiwanese people may trace their ethnic ancestry to mainland China, the bulk of the country’s citizens today identify as uniquely Taiwanese. (Taiwan is also home to an Indigenous population that is frequently disregarded.)

Though in theory many Taiwanese would like complete independence, realpolitik has disregarded it. Because Taiwan’s situation is so delicate, Beijing established an anti-secession law in 2005 that permits China to use military action against the island if it decides to become an independent state. Thus, there is a great deal of discussion throughout the Indo-Pacific region and in the corridors of the US Congress on whether and to what degree Washington would support Taipei in a fight between Taiwan and China.

Taiwan’s ongoing presidential campaign, which will end with elections on January 13, is similarly motivated by this problem. Because of term restrictions, Tsai Ing-wen, the president of Taiwan and leader of the center-left Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), is unable to run for office again. Her party was born out of a pro-democracy movement that aimed to overthrow Taiwan’s Kuomintang party (KMT), which was the country’s one-party dictatorship. The DPP and KMT have dominated Taipei politics, ever since the island’s democratization in the early 1990s and the lifting of martial law in 1987.

The democratic KMT of today primarily engages in center-right politics. The DPP and KMT divide most on China, even if they agree on many social issues (Tsai’s DPP, for instance, supported the legalization of same-sex marriage in Taiwan). Although the positions of the two parties are different, the KMT typically wants stronger connections with China and perhaps even some sort of reunification discussions, while the DPP views Taiwan as an independent nation and has made an effort to become closer to Washington. Beijing pledged to “fight” during Tsai’s visit to the US last year, during which she met with US House Speaker Kevin McCarthy. In the meantime, a former KMT president became the first Taiwanese leader to visit the Chinese mainland since 1949.

Even though Tsai has attempted to strengthen Taiwan’s relations with the US with more authority, the island has been losing ground in its protracted fight for international recognition. Compared to Beijing, only 13 n ations recognize Taipei now. Latin America provided Taiwan with much of its initial international support, but since mid-2017, all of the countries in the region have moved their alliances from Taipei to Beijing: the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama. Taiwan’s growing diplomatic isolation, driven chiefly by countries’ economic interest in the mainland, has only heightened Taipei’s fears of a potentially militant Beijing.

Lai Ching-te, Tsai’s vice president, has obtained the DPP’s candidacy for president and is promising consistency. Similar to Tsai, he is despised by China and argues that Taiwan is self-governing, without addressing the contentious issue of a formal declaration of independence. Hou Yu-ih, the KMT’s nominee, is the mayor of New Taipei, the region that surrounds the capital, and she wants to have discussions with China to ease tensions. A third-party candidate running on behalf of the relatively new Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) joins the two. Ko Wen-je, the group’s nominee, has primarily focused on appealing to voters’ domestic concerns about housing, the economy, and energy security. She does not, however, have a clear stance on China. Current polling shows Lai with a slight lead over Hou, while Ko trails far behind.

Given that Taiwan’s January 13 election marks the first on the calendar in what will be the largest election year in history, it’s going to test the mettle of governments, journalists, politicians, tech companies, and the country’s entire democratic system. Understanding how the onslaught of disinformation will impact the opinions of the Taiwanese public will be critical for Taiwan’s election, but much like in 2020, the tactics and behaviors will likely be duplicated elsewhere, not only by the Chinese Communist Party but also by other actors. Based on previous experience and geopolitical trends, social media, further weaponized with artificial intelligence, will play an outsized and destructive role in

these elections.

Disinformation and propaganda are methods that would be recognized by strategists in the era before even paper was invented, yet each technological cycle brings innovation to the sphere that usually leads to disastrous consequences. To better illustrate this notion, we can look to perhaps Russia’s most notorious disinformation campaign to date – Operation Denver. This was an active measure campaign designed to persuade the world that the United States was responsible for the creation of the AIDS virus. The effort began in 1983 with the planting of a fictitious letter to the editor of a local Indian newspaper, created some years earlier by the KGB precisely for the purposes of spreading pro-Soviet propaganda. The letter, entitled “AIDS may Invade India,” was purported to be written by a respected American scientist and claimed that the virus originated at the US chemical and biological warfare research facility in Maryland. This original source was then cited in later KGB efforts to further spread the conspiracy theory. Thirty years later, this conspiracy theory remains deeply rooted in some communities, not only the Global South, even in the West – according to one study as many 12% African Americans believed AIDS was a US bio-weapon spread by the CIA in their community and in Africa on purpose. Now malicious actors in the international arena can churn out dozens of similar campaigns in a single day.

Technological changes in digital publishing and artificial intelligence have enabled an entirely novel strategy of using these age-old principles of propaganda – where purposely created seemingly credible and seemingly mainstream media outlets can directly deliver the narrative payload to the target audiences at a fraction of the cost even compared to previous age of centralized mass media. This means information operations can be created and put into use faster, at greater volume, and at lower costs than was the case with Soviet-era campaigns. For example, Russia used this technique on social media platforms to spread a fabricated story about US aid to Ukraine being diverted to buy superyachts for Mr. and Mrs. Zelenskyy – and even though it was easily debunked in a very short time, the damage was already done as some Congressmen mentioned the story as they expressed reservations about renewing US aid to Ukraine.

Russia has inherited the rich Soviet legacy of information operations and put it to early use by pioneering instrumentalization of social media for large-scale high-efficiency influence operations around the globe. Other authoritarian regimes like China and Iran are quickly catching up on the game as they simultaneously turn the screws on domestic digital repression. Russia and increasingly China are also exporting digital authoritarianism packages to the third world, while getting increasingly sophisticated in sowing discontent in other countries through the use of generative AI in information operations.

The recent elections in Argentina were marked by the widespread use of AI in campaigning material. Generative AI has also been used to target candidates with embarrassing content (increasingly of a sexual nature), to generate political ads, and to support candidates’ campaigns and outreach activities in India, the United States, Poland, Zambia, and Bangladesh (to name a few). The overall result of the lack of strong frameworks for the use of synthetic media in political settings is set to create a climate of mistrust regarding what we see or hear.

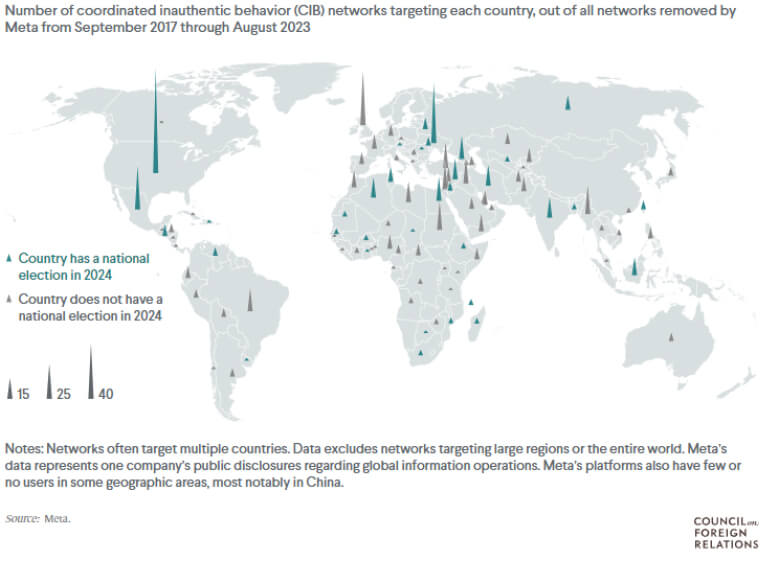

Within a matter of just a few years, Beijing has copied and successfully used many of Russia’s information warfare techniques. But unlike Russia, the Chinese government believes it has the ability and even the mandate to turn its domestic online surveillance apparatus outward, to disrupt and, perhaps eventually, even control global narratives in real time. Taiwan has long experienced advanced, persistent Chinese cyberattacks and influence operations. And the Taiwanese election mid-January will be a herald of things to come – disinformation in Taiwan’s information space has already increased by 50% since last year. Online disinformation can significantly impact Taiwan’s democratic process, particularly when it reinforces offline rumors. Chinese disinformation campaigns frequently spread rumors designed to reduce the confidence of Taiwan’s people in its government and spread fear and panic throughout the society. During elections, such disinformation campaigns often target swing voters who can influence the outcome. Taiwan is treated as a testbed for information manipulation campaigns by the Chinese Communist Party, much as Ukraine has historically been for Russia. The election will be a showcase of how China is changing the tone and distribution mechanisms for its influence campaigns to prey on more localized concerns and to use platforms outside of the mainstream. We predict the use of generative AI to become more prevalent, complex, and effective. The parent company of Facebook and Instagram recently took down more than seven thousand accounts linked to a Chinese influence operation in its largest ever takedown. These metrics indicate that the presence of disinformation around the Taiwanese elections will be greater and more insidious than previously seen, with more state and non-state actors watching and eager to adopt these measures in many of the other elections the world is facing in 2024.

Since 2017, the technology giant Meta has disclosed more than two hundred coordinated inauthentic behavior operations on its platforms, across more than one hundred countries. Meta has close to four billion monthly active users across its platforms, including Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram.