At the end of June, a Russian mercenary organization known as ‘Wagner’ has mutinied against its state backers in a bid to keep its independence. The rebellion seriously shook the political system in Russia and weakened the position of President Putin, even though the mercenaries ultimately capitulated and accepted a Kremlin offer. The Russian government has outsourced its information operations through a complex web of companies, run by the head of the mutiny; businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin, who has also been responsible for coordinating secret elements of Russian foreign policy in the Middle East or Africa. In the wake of the rebellion, the Russian government is now looking to restructure its psychological operations, reassessing its position in countries where the policy was covertly executed by the mercenaries. There is also the additional risk that mutineers collaborate, forming a new criminal collective.

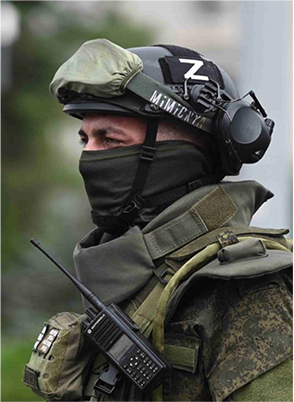

The end of June witnessed the culmination of a long-running dispute between the Russian army and Yevgeny Prigozhin; a warlord executing Russian foreign policy, who is also a purveyor of information operations against the West and head of a private business empire. The mutiny of his private military company, ‘Wagner’ was triggered when the Russian Ministry of Defense tried to accelerate its control.

Even more shocking than the mutiny itself was the understated reaction of the Russian army, compounding the ease with which the Wagner group mercenaries took Rostov, a city of a million, which included the important Russian headquarters of the Southern Military District. The group then sent a column of several thousand fighters towards Moscow, which stood down on reaching a government settlement.

Yevgeny Prigozhin was born in 1961 into a well-to-do Soviet family. His mother was a doctor, and his father a mining engineer, however from adolescence he was already known to the juvenile courts for burglary and dealing in stolen goods, culminating with the aggravated robbery of a young woman, whom he robbed at knifepoint and nearly strangled to death. In 1981 he was sentenced to a total of 13 years in a penal colony for a plethora of criminal activities.

He left prison 10 years later as the country was slowly beginning to embrace free enterprise, and opened his first hot dog stand, which quickly became a success. From this humble beginning, Prigozhin expanded into a network of supermarkets and eateries, later founding the upscale, “New Island” restaurant in downtown St. Petersburg, frequented by a then-unknown city hall official; named Vladimir Putin.

Despite this, they didn’t meet until later, when Prigozhin and his associates needed an official ‘helping hand’ with their chain of casinos. At that time, gambling businesses were under the oversight of the city official; Putin, and casinos were legally required to take the city as a partner and share revenue. Despite the business booming, the casinos were turning a loss on paper, however, no investigations into corruption were made, despite numerous allegations.

A mere few years later, Prigozhin was hosting state dinners for Vladimir Putin at his establishments, with the presidents of France or the United States attending as guests.

By the time Vladimir Putin had established his authority as president of the country, Prigozhin was expanding into the catering business, with his holding company; “Concord”, bidding for contracts in Moscow (including in the presidential palace, federal administration, and the ministry of defense). According to the Russian media, the value of these contracts reached over $3 billion. However, this is likely to be a conservative estimation. In addition to this, recent investigations revealed that Prigozhin secretly controlled further companies doing business with the state, giving him a near monopoly in catering services for the city of Moscow, as well as many state organizations.

Indeed, a police raid found documents and company stamps belonging to as many as 600 businesses in Prigozhin’s residence, most of them not legally tied to or owned by Concord group, but mostly managed by personnel working for companies, belonging to the holding. The true extent of the Prigozhin empire is thus extremely difficult to trace, and it is currently unknown to what extent these businesses will be shut down, taken over by competitors or left in operation.

As a part of his lucrative business with the state, Prigozhin elevated his relationship with the Kremlin ten years ago, when he used his catering profits to fund the creation of the now infamous Internet Research Agency, known in the West as The Troll Factory. The agency was then used as a bedrock for Prigozhin’s new business interest – a media group – which is now a sprawling empire, playing an important role, firstly in influencing domestic public opinion (and vilifying the opposition, as ordered by the Kremlin) but also in election meddling in countries, deemed hostile to Kremlin, and undermining social cohesion by promoting pro-Russian narratives, or supplying autocrat support packages. The nature of the operations is a mixed bag of private enterprise and deniable government-ordered information operations.

The two approaches then intersect into so-called autocrat support packages, which are a combination of traditional tools of political marketing services with fake social media activity (used to support the power of various autocrats from Africa and Asia), and the projection of false images of popular support to third country audiences. Foreign countries pay for the services, but the customers are vetted by the Kremlin.

On top of that, there is also a significant share of the standard advertising market and the ability to set the news agenda through the key node of the media empire, the RIA FAN news agency.

A further step of taking on roles typically performed by government – either overtly by the military, or covertly by the secret services – was establishing Wagner PMC, a private military company, operated by Yevgeny Prigozhin on the behest of Kremlin, since 2014. Prior to its establishment, some factions of the Russian military advocated for the use of private military companies to execute government policy in deniable operations. Most of these advocates were from military intelligence, with general Vladimir Alekseyev being the most senior known representative of this school of thought (often mistakenly labeled Gerasimov doctrine).

Recently revealed documents reveal fighters of Wagner PMC were among the first local militia groups that were used by the Russian government in its initial invasion of Ukraine in 2014. They also performed the role of Russian infantry in the Syrian war, where the operation to prop up the regime of Bashar al-Assad was sold to the Russian public as an air-campaign-only type of engagement in which no Russian servicemen were expected to die. It quickly became clear, however, that the Syrian army needed help on the ground: this was outsourced to the Wagner group, who were equipped and logistically supported by the Russian army. Prigozhin thus assumed the role of a modern-day Wallenstein, a warlord operating on the behest of the government, while pursuing his own business interest at the same time.

A similar scheme was then applied in other countries like Libya, and other African nations like the Central African Republic, Mali, and Sudan.

The reason is likely multifactorial, however a cynic might say it was a desperate act of a man who overestimated his position in the system, his relationship with the president, and usefulness for the state, at the same time underestimating the impact of his challenges on key players in the regime (including intended targets like defense minister Sergei Shoigu, and chief of the general staff Valery Gerasimov, both of which are extremely close to Putin).

It could be argued that the conflict between Prigozhin and the highest echelons of the army has been smoldering for years, or at least since 2018, when the Russian army deliberately let the US Air Force wipe out a unit of Wagner’s troops, near Syria’s Deir ez-Zor. It is alleged that the army’s high command resented the competition of overpaid mercenaries, bound by almost no rules, and did not intend to accommodate Wagner, beyond the point of necessity. This inflamed Prigozhin’s anger, fueling his personal attacks on the defense minister and the chief of general staff, whom he has consistently attacked as corrupt, inefficient, incompetent, and generally unworthy of their positions. The behind-the-scenes war for the president’s favor was ultimately won by the army, rather than by the increasingly unmanageable warlord Prigozhin, who was clearly not content with his multi-billion-dollar business empire.

The catalyst for the mutiny was the recent announcement by the Russian Ministry of Defense that all private military companies and volunteer units would have to sign contracts with the Ministry of Defense, unifying the command structure at the front, under unambiguous military authority. This would mean the end of Wagner group‘s independence, jeopardy for Prigozhin’s billions, and sidelining of his nascent political power.

The aim of the mutiny, therefore, was presumably to force the preservation of Wagner independence, and assert the role of Prigozhin as a powerful warlord with a personal army and ever-flowing revenue. The rebellion was arguably therefore not a question of overthrowing power structures, but an attempt to save this ‘enterprise’ in the hope that Wagner battlefield merits would be taken into account. As it stands, these merits are likely why Prigozhin has escaped the whole adventure with his life, albeit at the expense of his political power, and questionably greater expense of his business empire.

Some contend that Prigozhin failed to appreciate that this action would become a public challenge to Putin himself, but most would no doubt feel that it is almost unbelievable that such an entrenched beneficiary of the system should have made such a huge error of judgement.

One of the crucial parts of Prigozhin’s power in Russia has been his media empire. This part of the business was officially shut down earlier this month, and other companies from the media group are reported to be closing in the coming week. Analysts speculate, however, that the core information operations and the psy-op part of the media group will be restructured and resurrected.

The Kremlin needs the services provided by Prigozhin’s troll factories, and will likely seek to save the capability, under leadership of a different pro-Kremlin oligarch. Analysts speculate that this vacuum could be filled by the banker Yuri Kovalchuk, who owns most of the privately-operated media in the country and is a close friend and ally of Vladimir Putin.

Another question being discussed by analysts is the recent hacking activity, targeting Dozor; a Russian satellite communications company, in which the PMC logo was posted, and hundreds of files were leaked, (some of which link the FSB to Dozor, as well as the passwords of Dozor employees).

The attackers claim that they have damaged satellite terminals and confidential information stored on Dozor’s servers, but this has not yet been confirmed. A pro-Ukrainian, ‘false flag’ operation remains very much a possibility: as Ukrainian cyber auxiliaries and psy-op operators have been using the mutiny to sow retaliatory chaos, increasingly targeting Russian social media, but also radio broadcasts in cyber-enabled information operations, inserting messages exploiting uncertainty caused by the Wagner mutiny.

The hackers were also able to exploit the chaos in the informational space, created by the lack of a coordinated response by the Russian government, inserting messages, stating Russia had declared martial law in response to a large-scale invasion. The operation gained enough traction to draw an official denial from a Kremlin spokesman.

Analysts are not yet sure of the perpetrators of the satellite company hack, however if this operation was conducted by hackers affiliated with Wagner PMC, it is likely that the collective would ignore the offer to sign contracts with the Russian military, offering its services on the black market instead. According to the deal between Wagner and the Kremlin, its base should move to Belarus, where the local government is not likely to put much pressure on the hacking element of the business, opening the possibility for a new powerful criminal hacking group to enter the market after cessation of its work on the behest of the Kremlin.

Although the immediate threat to the Russian regime has been averted, damage has nonetheless been done. The perception of Vladimir Putin’s power and his apparent invulnerability has been eroded by the mutiny, and the Russian political system has arguably been weakened in a way that will be difficult for the Kremlin rulers to overcome: For 24 hours the emperor had no clothes, and the Russian people will now always remember that.

The question now is who will run the Kremlin’s information operations, what will become of Prigozhin‘s empire. The situation has no easy solution for the Kremlin because the political model from the ‘Thirty Years War’ will not be easy for the Kremlin to cut off, without losing its laboriously built credibility in countries, where it operated through Wagner PMC.

It would be safe to assume that Prigozhin is now a Russian persona non grata, but has he become so powerful that the Kremlin will be obliged to let him keep (at least temporarily) part of his business empire, and continue to represent the Kremlin on other continents? This question is just one of the many levels of absurdity of this rebellion, to which only time has the answer for.