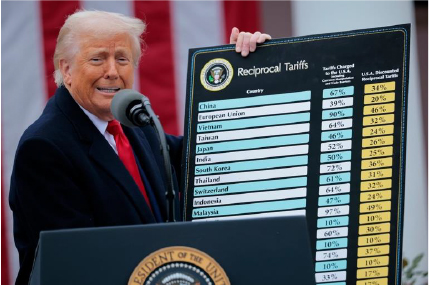

On what President Donald Trump dubbed “Liberation Day”, he unveiled a sweeping set of import tariffs, heralding them as the key to bringing manufacturing jobs “roaring back into our country”. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick amplified this vision, painting a picture of “millions and millions of human beings screwing in little screws to make iPhones” in American factories. The rhetoric is bold, nostalgic, and deeply rooted in Trump’s long-standing protectionist worldview – a perspective he’s championed since the 1980s when he decried Japanese companies for “ripping off” the United States. Yet, despite the fervor, a growing body of evidence and analysis suggests that Trump’s tariffs will not only fail to revive manufacturing employment but will likely harm the U.S. economy, raise consumer prices, increase unemployment, and exacerbate geopolitical tensions

At the heart of the policy is the belief that high tariffs will incentivize domestic production, thereby restoring manufacturing jobs lost to globalization. However, this assumption overlooks several critical realities about modern manufacturing and global supply chains.

Tariffs Undermine U.S. Competitiveness

Tariffs are often framed as a tax on foreign goods to protect domestic industries, but they also function as a tax on business inputs. Over half of U.S. imports consist of industrial supplies, materials, capital goods, and automotive parts – essential components for American manufacturers. By increasing the cost of these inputs, tariffs raise production costs, making it harder for U.S. firms to compete globally. This isn’t mere speculation; evidence from Trump’s first-term trade war (2018-19) shows that higher input costs led to manufacturing job losses five times greater than the job gains from import protection. The current, more aggressive tariffs are likely to amplify this effect, stifling manufacturers’ ability to expand output and hire workers.

Automation and Structural Shifts

Even if tariffs could spur demand for domestic goods, the nature of manufacturing has changed: automation has reduced the need for low-skill labor in factories, meaning that even new facilities would employ fewer workers than in decades past, and building a factory to produce iPhones – as Lutnick envisions – would likely involve highly automated processes, not armies of workers assembling products by hand. Moreover, many jobs lost to globalization have been replaced by service-sector jobs, which often pay higher wages. The average manufacturing worker in the U.S. earns less than the average service-sector worker, and “screwing in little screws” jobs would likely offer even lower wages, making them unattractive to many Americans.

Time and Investment Delays

Building new manufacturing facilities – whether for semiconductors, cars, or clean energy – takes years, not months. Tariffs may be enacted with a stroke of a pen, but the infrastructure and supply chains required to replace imported goods cannot be conjured overnight. This lag undermines the promise of immediate job creation and exposes the economy to prolonged uncertainty as businesses wait for clarity on long-term trade policies.

Policy Volatility Deters Investment

Trump’s tariffs introduce significant uncertainty into the business environment. U.S. manufacturers rely heavily on imported intermediary goods, and wild swings in tariff rates make it difficult for firms to forecast costs and plan investments. Since Trump’s inauguration, businesses have scaled back hiring plans, wary of committing to multiyear projects in an unpredictable policy landscape. The threat of tariffs on obscure territories like the Heard Island and McDonald Islands – home to penguins, not people – underscores the haphazard nature of the policy, further eroding investor confidence. Just during the single business day of April 23rd, various parts of the US administration talked up a reduction of tariffs on China to 50%, only to dismiss the idea and return to 145% hours later; to offer tariff exemptions to car manufacturers (days after giving the same exemption to phone and computer manufacturers, which were supposed to be the big success of the tariffs) only to follow with news that the White House seeks deals but might turn the tariffs even higher than before.

Under such circumstances not many CFO’s are going to sign off on a CapEx project in a country with economic policy that is this unstable, even if the investment was otherwise tenable and not threatened by the other problems tariffs cause.

Labor Market Constraints

Even if new factories were built, the question of who would fill the jobs remains: the U.S. unemployment rate is already near historic lows, meaning most people who desire jobs already have them. While some individuals are outside the labor force, attracting them would require significantly higher wages – unlikely for low-skill manufacturing roles. Forcing Americans into low-wage jobs stitching sneakers or assembling electronics is neither economically viable nor socially desirable. The average American consumer wants to buy sneakers and iPhones, not to make them.

Beyond failing to revive manufacturing, Trump’s tariffs are poised to inflict broader economic harm. Economic modeling from the Budget Lab at Yale University estimates that the “Liberation Day” tariffs will reduce U.S. real GDP growth by 0.4% annually. While this may seem modest, it represents a 20% reduction in growth – assuming an annual GDP of approximately 2% – which compounds over time into significantly lost economic potential. Consumer prices are also expected to rise as tariffs increase the cost of imported goods and domestic products reliant on foreign inputs. This inflationary pressure, coupled with reduced economic activity, could push the U.S. toward recession, as market uncertainty and volatility – reminiscent of the post-Lehman Brothers collapse – grow.

The tariffs also contradict Trump’s deregulatory agenda. Implementing complex tariff schedules requires extensive government oversight, including detailed classification systems, inspections, audits, and penalties. This administrative burden falls on both regulators and businesses, increasing costs and red tape. Furthermore, tariffs incentivize cronyism, as companies lobby for exemptions or higher tariffs on competitors, entangling government officials in decision-making – a far cry from deregulation.

A core driver of Trump’s tariff policy is his belief that trade deficits represent foreign countries financially exploiting the United States. This view stems from two fundamental misunderstandings: first, Trump and his advisors misinterpret the GDP accounting equation, believing imports reduce GDP because they are subtracted in the formula when in reality, imports are added to consumption and investment and then subtracted to avoid double-counting (meaning they have no net effect on GDP). The second assumption is that blocking imports will lead to a one-for-one increase in domestic production, however, this does not account for consumer decisions to forgo purchases, reducing overall economic welfare, or firms facing higher costs (as seen in the layoffs among U.S. auto and steelworkers due to costlier inputs).

Trade deficits are not inherently good or bad; they reflect a complex interplay of factors, including international capital flows, comparative advantage, and supply chains. For example, if an American factory buys a $100,000 Japanese or a German CNC machining tool, financed by foreign investment in U.S. Treasury bonds, it contributes to the trade deficit. But if the machine enables $500,000 in production, the U.S. economy benefits. Trump’s focus on eliminating trade deficits ignores these nuances and risks harming industries that rely on global supply chains.

The U.S. trade deficit with China, which has contributed to de-industrialization, is a legitimate concern. However, broad tariffs on all trading partners, including allies, are likely to accelerate de-industrialization by raising costs and provoking retaliation. Reducing imports is less critical than boosting exports, a goal undermined by tariffs that weaken U.S. competitiveness and invite reciprocal trade barriers.

Trump’s tariffs are partly a response to China’s trade practices, which have long been a point of contention. The narrative, echoed by Vice President J.D. Vance in his memoir Hillbilly Elegy, holds that China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 allowed it to “steal” American jobs and destroy industries. This view is half-true. China’s WTO accession was not a gift; it followed 15 years of grueling negotiations, resulting in a 1,500-page agreement that imposed stringent conditions on China, including market-opening measures and the dismantling of discriminatory practices. However, China later reneged on many commitments, reverting to state-controlled economic policies under leaders Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping.

Successive U.S. administrations – under George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and even Trump – failed to fully leverage WTO enforcement mechanisms to hold China accountable. This failure, compounded by corporate greed and geopolitical miscalculations, allowed China to become the world’s largest exporter within a decade of WTO membership. While targeted tariffs on China could be part of a strategy to address these imbalances, Trump’s indiscriminate tariffs risk alienating allies and disrupting global supply chains, further weakening U.S. manufacturing which depends on foreign intermediary goods to produce larger value-added items such as planes and agricultural machinery for example.

Markets have reacted to Trump’s tariffs with volatility reminiscent of the 2008 financial crisis. Investors are demanding a so-called “moron risk premium” – higher yields on U.S. assets due to perceived policy incompetence. Foreigners own as much as 30% of U.S. assets, which are now under what is in developing countries called capital flight, which is causing a tremendous loss of value for the average equity holder.

The erratic tariff formula, which imposes rates based on a flawed calculation of trade deficits, has fueled uncertainty. For instance, the formula assumes a country with a $50 million trade deficit on $100 million in imports levies a 50% tariff, leading to a “reciprocal” U.S. tariff of 25%. This approach inflates tariffs fourfold and applies a minimum 10% rate even to countries with trade surpluses like Australia. Such arbitrariness undermines confidence in U.S. economic management, driving down asset prices and business sentiment.

Trump’s supporters argue that tariffs will deliver concentrated benefits to manufacturing workers while imposing diffuse costs on consumers. This is a miscalculation. The policy is a lose-lose proposition, harming both manufacturing workers – through layoffs and reduced competitiveness – and consumers, who face higher prices. The broader economy suffers from slower growth, increased unemployment, and diminished global influence. Even the nostalgic vision of restoring America’s industrial heartland, as articulated by Vance, ignores the economic realities of low-wage, low-skill jobs that few Americans want.

Trump’s tariffs also carry significant geopolitical consequences in cyberspace.

Some organizations might be facing hard budgetary choices, but cutting back on cybersecurity would be a critical mistake as cyberattacks typically increase during economic downturns – and states like China, Iran, or North Korea are expected to use their resources to aid their flailing business within a chaotic geopolitical environment. Cybersecurity should therefore be viewed as vital for continuity and competitiveness. China is already running a massive-scale state-backed IP theft programme, which is part of a much larger industrial strategy that China uses to displace companies from competitor countries. Any geopolitical strains will incentivise Beijing to focus more resources on its cyberespionage.

Indeed, China has a bigger hacking program than that of every other major nation combined, and any large company in industries outlined in Chinese development plans will need to invest in external threat landscape management solutions to stay ahead of relentless and repeated assaults by Chinese hackers. China is also trying to push into cracks in Western critical infrastructure, and according to fresh media reports, Chinese officials privately acknowledged in December that Beijing was behind a series of aggressive cyberattacks targeting U.S. critical infrastructure.

Chinese representatives supposedly connected years of cyber intrusions into U.S. ports, water systems, airports, and other key sectors to Washington’s growing support for Taiwan. These intrusions, previously denied by Beijing, have been linked by security researchers to a group known as Volt Typhoon. The admission, albeit indirect and veiled in diplomatic language, came as a surprise to the American delegation. Chinese officials had long denied involvement, often blaming criminal groups or accusing the U.S. of exaggerating. However, during this meeting, American officials interpreted the comments as a tacit acknowledgment of responsibility – along with an implicit warning over Taiwan.

Since the Geneva meeting, U.S.-China relations have further deteriorated amid an escalating trade war, which is why similar activity is expected to dramatically increase. Top Trump administration officials have vowed to step up offensive cyber operations against China, while Beijing continues to exploit access to U.S. telecommunications systems gained through a separate breach tied to another hacking group, dubbed ‘Salt Typhoon’.

Compounding concerns, the administration recently announced sweeping layoffs of cybersecurity personnel and dismissed both the director and deputy director of the National Security Agency, moves which have raised alarms among intelligence officials and lawmakers about weakening national defenses at such a critical time.

Donald Trump’s tariffs reflect a deep-seated commitment to protectionism, unshaken by empirical evidence or economic reasoning. While the desire to address trade imbalances, particularly with China, is understandable, broad tariffs are a blunt and counterproductive tool. They raise costs, deter investment, and invite retaliation, all while failing to deliver the promised manufacturing revival. Instead of fostering economic growth, they risk recession, inflation, and geopolitical instability. A smarter approach would arguably focus on targeted measures to boost U.S. exports and competitiveness, coupled with robust enforcement of trade agreements, but for now, Trump’s tariff gamble threatens to undermine the very economic greatness he seeks to restore.

The lack of policy clarity is what truly rattles businesses since most business leaders want predictability first to schedule out long-term capital investments and right now, no one has a clear read on what’s coming, and many large projects are simply put off until expected midterm elections the Republican party is set to lose, with the new congress possibly clawing back the power to set tariff rates. Either way, it is predicted that manufacturing will not come back to the U.S. en masse, the global economy will suffer, and the risk of cyber fallout will run high for months and even years.