When dealing with the questions of the strategic relationship between China and Russia, we can learn much from the official rhetoric. At the beginning of February 2022 there was talk of the friendship between the two countries “having no boundaries and there being no forbidden zones in mutual cooperation”, a theme the Kremlin has tried to highlight again and again, by spring 2023 the high level meetings were summed up in a different tone: ‘the friendship between the two nations has a solid foundation and multilateral cooperation between the two states has very broad prospects’. Put simply, the seemingly warm friendship is in fact a highly transactional affair between countries that are closer to rivalry than friendship, and that are bound together only by a single vision of a common enemy, not a shared vision of a future world. While the two countries are engaging in limited cooperation in intelligence sharing, especially in the cyber realm, there is no substantial basis for the theory of an increasingly tightly knit strategic alliance that will put Russian–Chinese “fortress Eurasia” on the map and in direct confrontation against the rest of the world.

The relationship between China and Russia will be one of the key determinants of the future of the Eurasian landmass. While many analysts assess their relations as amicable, already tightly knit and heading for firm future integration, the authors of this report are questioning this “common knowledge”. Our position can be easily demonstrated in official statements put forward by Beijing and Moscow.

Before the annual summit this year, Putin wanted three things from China: a deal on hydrocarbon pipelines, arms supplies and generous loans. He got none of those things. The Chinese secretary offered kind words of support towards Putin himself and expressed confidence that he would certainly be able to defend his mandate in next year’s elections, while Putin himself has not even announced his candidacy. We also saw Chinese statements about the beginning of something new and about a new world order and about changes that have not been seen for 100 years, but this is just a reiteration of the usual Chinese government line about a world order in which Beijing will be the key player instead of the US and in which there is implicitly no place for Russia as an equal partner to China. Beijing made it clear that it was not abandoning Russia, but is certainly not going to help Moscow in a way that would jeopardize its global position.

Instead of drones and artillery ammunition, which Moscow clearly wants, president Xi offers only kind words. China is willing to support Russia’s political stance on ‘NATO aggression’, but it is in no way willing to actually risk finding itself in an economic and political confrontation with the West over Russian campaigns in Europe. After all, the volume of Chinese trade with North America and Europe is roughly nine times that with Russia.

The absence of any commitment to provide Russia with concrete and substantive support in its war with Ukraine or the absence of a willingness to explicitly recognise the annexation of Ukrainian territory was clear evidence of Chinese preference of Western commerce over strategic partnership with Russia on changing of the world order.

The balance of power has changed. Russia is a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, not the other way around. China is a huge economic power and its gravitational pull is gradually drawing Russia into its orbit, especially strongly now, at a time when Russia is being denied many of its Western markets and a significant portion of its dollar-denominated trade. Russian exports to China are likely to double this year from the pre-war period to somewhere near a quarter of Russia’s foreign trade, with Chinese firms sure to fill the vacancies in industrial, transport or infrastructure supply and construction in Russia.

But increased trade or trade dependence does not mean vessel status or absolute power over the counterpart. We can point to the talk of Putin’s energy weapon, which will force Europe to be subjugated to Russian blackmail and prevent effective aid to Ukraine. Thus, to assume that Russia has somehow already become a vessel of China simply because of the unequal balance of power in some areas of trade is very premature.

China supports Russia politically because its actions weaken the West, which suits the long term goals of Beijing. At the same time, though, the war is galvanizing Euro-American relations, and China would be very keen to ‘peel Europe away’ from America, but that is not going to succeed any time soon given the political cover Beijing offered to Moscow. But Xi Jinping has spent too much political capital on confronting the United States to turn away from his ‘ally’ in Moscow. This is especially so at a time when the only uniting line between Democrats and Republicans in the US Congress is the policy of halting China’s rise to power. Thus, direct military support for Putin’s invasion from China can probably only be expected if a total collapse of the Russian military is imminent. By limiting itself to words of support, Beijing is keeping access to lucrative trade with the West, while the latter must expend resources on its military rivalry with Russia.

For its part, Russia is trying to ride on Xi Jinping’s personal confrontation with the West, with the aim of plunging the world into a new multipolar system in which Russia would regain its lost power and superpower status. However, even before the start of the Ukraine war Russia has been on a path to become a second tier power vis-a-vis China, a process only accelerated by its needless aggression in Europe, which puts Russia increasingly into a position of economic dependence on China. At the same time, Russia is a nuclear power and its political dependence on China has clear limits. As Russian dependence deepens, possibly pressure on Russia from China to stop supplying arms to Chinese rivals like Vietnam and India for example would certainly be a moment when Moscow would take strong notice.

It is clear that president Putin is completely consumed by his own historical legacy built on a confrontation with the West – in which the war in Ukraine will be the cornerstone of his strategy. Thus he will need to agree to the kind of deal with China that he will need for the purpose of prosecuting his strategy. There are influential true believers in this strategy, who are currently forming the core of the Russian ruling elite, however the old-Soviet-siloviki-types like Nikolai Patrushev or Sergey Naryshkin are, like Putin, in their 70s and beyond, and the rising generation of today’s 50-somethings are anything but bling to the the strategic danger to Russia that is not c oming from the West but from China on their very own political timelines. Putin thus lacks a keeper of the flame for his project of confrontation with the West, and one can very easily imagine that sooner or later after his death a new Henry Kissinger will come on the scene and once again turn the paradigm of the great power triangle of the Russia-China-US relations upside down. Even in the intelligence and military strategy professionals, one can hear opinions stating that within 20 years Russia will have to decide whether to become an ally of the West of some kind or a vessel of China.

Those who speculate that China will soon swallow Russia or that the two countries will form a grand Eurasian alliance are committing an analytical error by overestimating the importance of economic factors in the Kremlin’s policy. Similarly, it was a mistake to overestimate Putin’s “energy weapon” – few could imagine that the Kremlin would destroy decades of economic cooperation infrastructure with Europe just to gain control of a handful of economically unimportant regions in southeastern Ukraine.

The Kremlin has paid the cost of the departure of major foreign investors, the closure of entire industries, the panicked flight of millions of people from government policies (mostly young, educated professionals who will be sorely missed by the economy), as well as budget deficits and the sending of tens of thousands of its own people to certain death. All of this without any on its long term strategy, therefore it is entirely premature to assume that China will be able to dictate terms to Russia that would be perceived as a significant violation of Russian sovereignty.

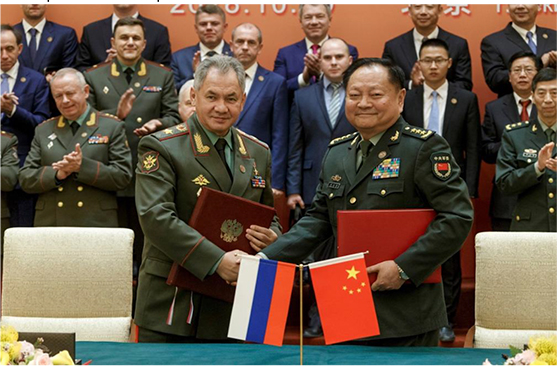

Russia and China show no signs of the advanced military cooperation as seen in the United States and its European or Asian allies. This includes, in particular, the establishment of multilateral military command centers, the joint deployment of troops, sharing of military bases and the formulation of a common defense policy at the highest level. The only exception remains the episodic establishment of Russian-Chinese operational headquarters for specific exercises and the occasional use of each other’s military facilities. Information from open sources does not indicate any intention on the part of Moscow and Beijing to establish permanent joint command structures. Beyond joint maneuvers, they neither provide each other with access to host nation logistics hubs nor seek to negotiate agreements to station troops or equipment on each other’s territory. Finally, there is no indication of an interest in discussing or formulating a common defense policy at any level.

The only area of significant cooperation between the two countries remains intelligence sharing. The Russian Security Council repeatedly issued statements on increased military cooperation with China, which according to some sources, has been followed by a secret memorandum on increased intelligence cooperation, especially in the field of cyber espionage and cyber counter-espionage.

The Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), has an agreement dating back to 1992 with the military intelligence side of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). This relationship serves a more technical kind of cooperation based on information that is of mutual value, mostly related to Western intelligence operations against the two countries and their interests. This is especially true in the cyber realm. The particular areas of cooperation are in military technology, espionage and information operations. The latest seems to be especially true as there has been some degree of cooperation and coordination observed by researchers in the activities of the Russian military intelligence unit 54777 and the Chinese 72nd Special Services Center, the main psychological warfare formations of both countries. The two units have been quite active in sharing its techniques and technologies with information flowing both sides.

At the same time, while the SVR is under agreement not to spy on the Chinese, it is the Russian military intelligence (GRU) that simply fills the gap. The military spies are institutionally less politicized and more tuned to the long term threats posed by China to the basically indefensible border Russia shares with her southeastern neighbor.

The Federal Security Service (FSB) is institutionally the greatest advocate of cooperation with China and also the greatest advocate of the need to watch the Chinese activities in Russia with suspicion. The service seems genuinely torn. Unlike other Russian intelligence agencies, it cooperates primarily with the Ministry of State Security, which is the main intelligence body in China, similarly responsible for counterintelligence against Western incursions. There is a considerable density of contact and sharing of techniques in cyber and information operations and domestic security between the two agencies as well as raw information and analysis sharing. However it is the FSB’s role as Russia’s primary counterintelligence agency that puts it at odds with China. And it is clear that it is increasingly alarmed and exasperated by Chinese intelligence activity within the Russian Federation, which clearly has been increasing, even before the war.

Chinese espionage is especially geared towards scientific and technical research which was publicized in a collection of individual cases in which the FSB openly called the Chinese state out and carried out various arrests which is in contrast to previous modus operandi, in which similar cases were dealt with without media coverage. Chinese espionage, especially in the form of cyberespionage, has gained almost unprecedented scope and sophistication since 2020, when there were already numerous incursions in Russian networks sponsored by the Chinese army.

While there is active cooperation between the Russian and the Chinese agencies on counterintelligence against the West, especially on technical aspects of cyber espionage and counter espionage and information operations, this usually ties to the common enemy in the West, we do not observe large cooperation of joint active operations in the cyber realm, let alone grand military or political alliance.

Just as China is clearly not willing to burn its fingers over Putin’s ambitions in Ukraine, neither would Russia be willing to risk a direct confrontation with the United States over the Chinese Communists’ ambitions to occupy Taiwan. For this reason, Russia and China do not form a defensive alliance, and this is unlikely to change in the future, even in spite of the faltering demographics of both countries, which are not flocking to immigration for obvious reasons and may shrink to half their populations by the end of the century. Putin will surely still be willing to make some concessions, but let’s not assume that the next political representation will be willing to stick to this trajectory just for the sake of Putin’s political legacy as the Russian system is based on opportunism, not ideology. While the two countries are engaging in limited cooperation in intelligence sharing, especially in the cyber realm, there is no substantial basis for the theory of an increasingly tightly knit strategic alliance that will put Russian–Chinese “fortress Eurasia” on the map and in direct confrontation against the rest of the world.