Training & Courses, Stealer Logs, Recruitments, Ransomware, Phishing, Monetizing, DDoS, Defacements, Doxing, Collaboration, Advantage Grabbing

In this report, we explore the various tactics and techniques employed by modern hacktivists. Among these, DDoS attacks are a common method used to disrupt websites by stressing them with traffic. This report provides insights into the evolving hacktivist landscape, demonstrating how the actions of these groups can have significant impacts on nations’ digital infrastructure. Governments that maintain certain stances may find their digital realms under threat from these cyber activities.

Hacktivists, who see themselves as digital activists, use their technical skills to promote social, political, or religious causes, and often operate under a banner of justice, targeting organizations or governments they perceive as oppressive, corrupt, or unjust. Motivated by a desire to bring about change, they use various cyber tactics to make their voices heard, from DDoS attacks and website defacements to data leaks and doxing.

In this report, we cover how hacktivists develop ransomware variants from leaked source codes to sell them for profit, breaching low-security private organization websites and using stealer logs to their advantage. We also explore the strategic alliances formed between hacktivist groups, their partnerships with DDoS or botnet developers, and their cooperation with state-owned threat actors.

Anonymous is one of the oldest and most well-known hacktivist groups, originating in the early 2000s and gaining renown for high-profile operations targeting organizations and governments; said to be motivated by issues of free speech, anti-censorship, and social justice. In its early days, Anonymous used forums like 4chan to organize and communicate, whereas contemporary hacktivism primarily utilizes social media platforms, such as Telegram, X, Facebook, and Instagram.

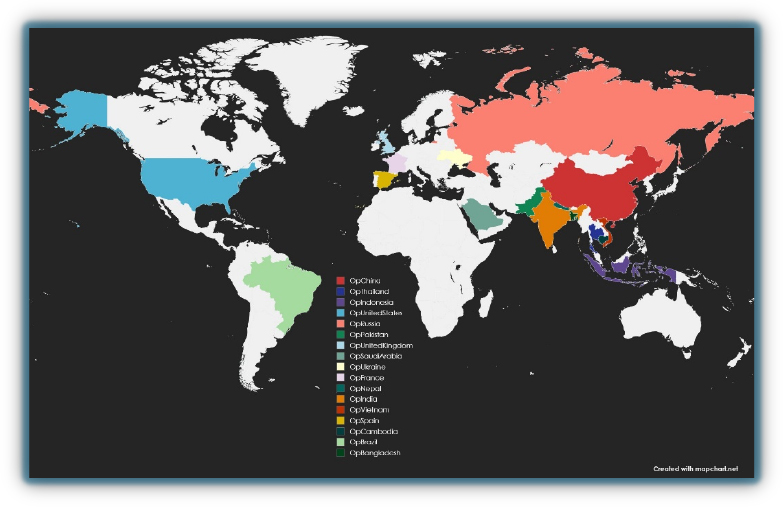

Hacktivist operations are often driven by geopolitical tensions as well as religious and racial conflicts, for instance surrounding the ongoing conflicts between Russia and Ukraine, and Israel and Gaza, but these hacktivists are also engaged in other operations, such as #OP initiatives, reflecting their involvement in other global conflicts.

#OpIndia #OpIsrael #OpNATO #OpUSA #OpRussia #OpUkraine #OpThailand #Opsputus #OpVietnam #OpIndonesia #OpJapan #OpUK #OpFrance #OpSpain #OpSweden #OpAustralia #OpChina

The above #Op initiatives are only a small sample of extracted hashtags from hacktivist channels. We explore some of these below in greater detail.

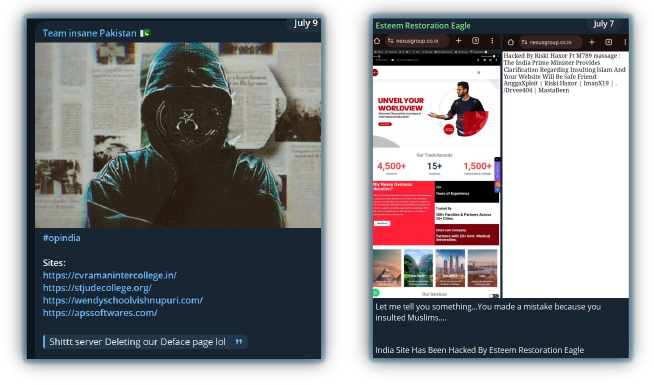

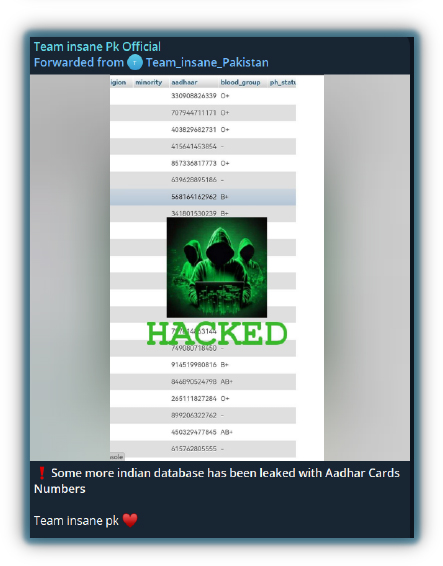

#OpIndia is a popular hashtag, used by hacktivist groups from countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Turkey, Morocco, and other Muslim-majority countries (as well as Sweden) that engage in DDoS attacks or deface Indian websites, and target government, individuals, or educational institutions. These attacks often occur in response to acts of violence or involve the spread of misinformation on social media.

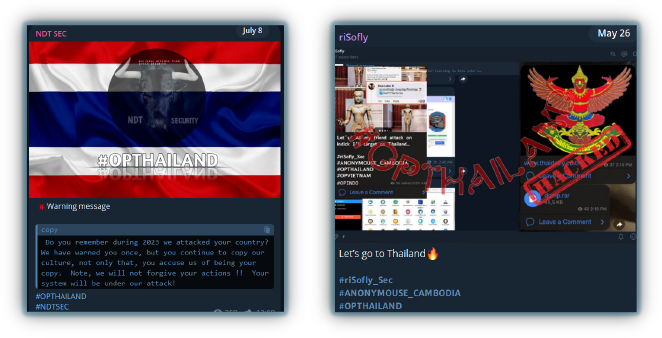

Cambodian hacktivists are attacking Thailand’s infrastructure due to ongoing Thai claims on Angkor Wat (in addition to cultural reasons – some reportedly assert that Thailand is “mimicking” their culture, which is proving an ongoing bone of contention). Another reason cited is Thailand’s silence on the Israel-Gaza conflict: hacktivist groups like “Anonymous Cambodia,” NDTsec, and riSofly are targeting multiple Thai banks, airports, and the Royal Thai Navy – their activities including leaks or launching DDoS attacks on websites, causing server disruptions.

Hacktivist groups like GlorySec state they target China’s infrastructure for a number of reasons, including protesting against the country’s oppressive laws and questionable human rights records. Groups such as the Muslim Cyber Army and SYLHET GANG-SG attack China because of its strict policies against Muslims, while the Anonymous Collective is motivated by animal cruelty issues. Additionally, recent actions in the South China Sea have prompted further attacks. Spectre 1877 hacktivists also believe that China is secretly collecting and selling personal data, driving them to launch cyberattacks.

Here are some of the active #Op initiatives currently running, highlighting the speed at which hacktivists respond to issues aligned with their beliefs or agendas.

Geo-political Issues: hacktivist groups frequently exploit geopolitical tensions to launch attacks, impacting government and public services.

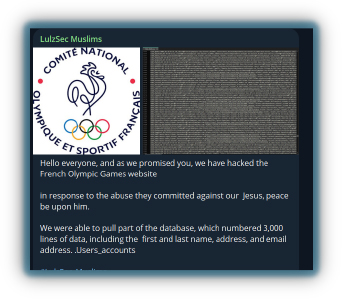

Religious Issues: attacks are sometimes carried out in response to perceived insults or threats to religious beliefs.

Upcoming major events: hacktivists target major events to gain attention and disrupt proceedings.

Hacktivists and their allies use various methods to harm the digital infrastructure of target countries. Below we explore these in greater detail:

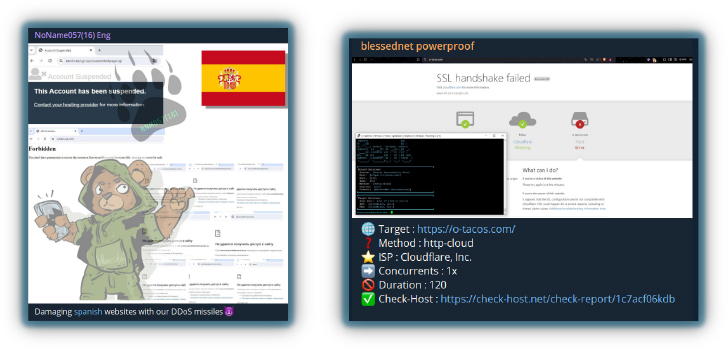

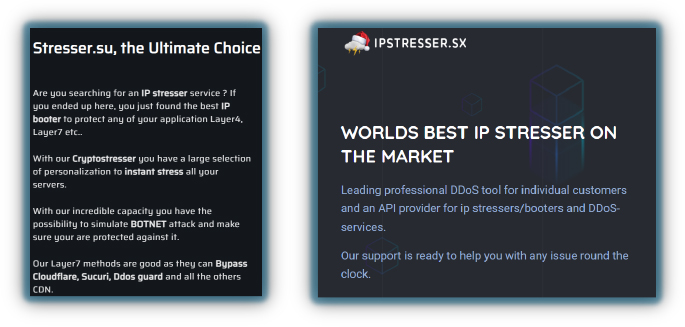

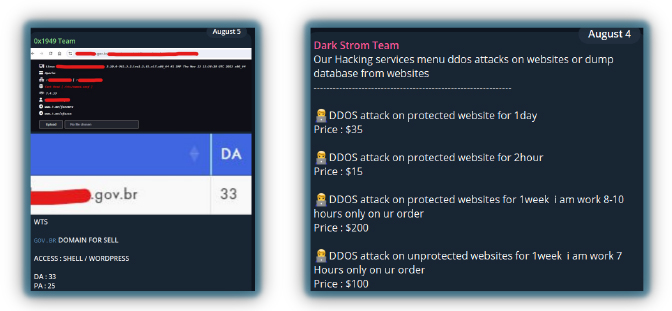

DDoS is a major tactic, with many tools available such as web-based IP stressors, Telegram-based DDoS bot services, and command-line DDoS tools. These tools can target layer 4 (transport) and layer 7 (application) of the OSI model and now often include features like CAPTCHA-solving services and the HTTP-TOR method to attack the TOR network.

Vendors promote their tools on Telegram, underground forums, and their own websites, often partnering with hacktivists to advertise their capabilities.

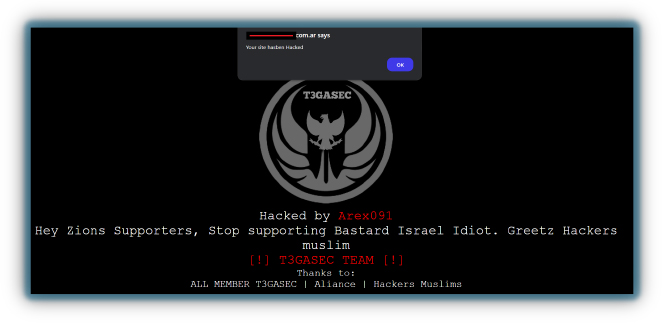

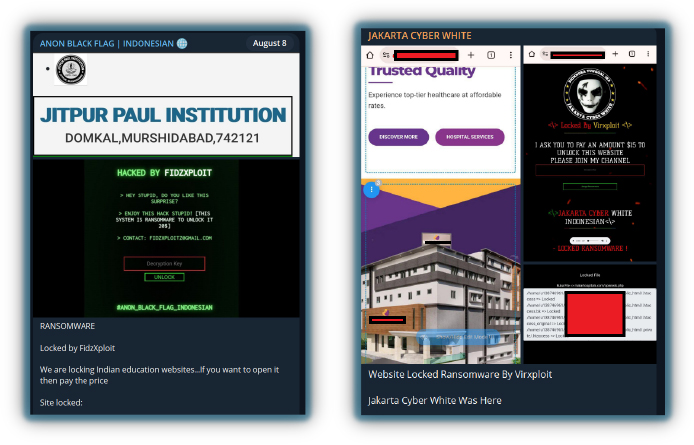

Web defacement is another tactic used by hacktivist groups, where messages to convey political or religious viewpoints are posted, or their target is mocked, often with a simple notice such as “Hacked by”, “We are in” (or even using an “Op” hashtag). Hacktivists use web defacement primarily to embarrass website owners, spread their ideology, or showcase their hacking capabilities, typically exploiting web vulnerabilities, such as cross-site scripting, SQL injection, or DNS hijacking.

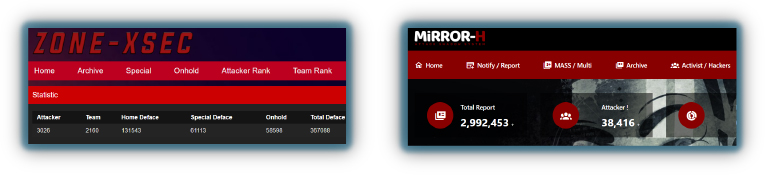

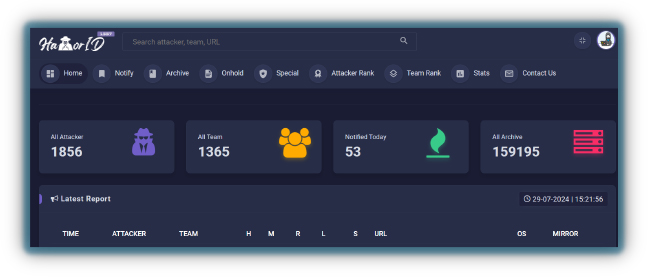

There are many resources where hacktivists can add their targets to a list, allowing others to track globally defaced sites. For example, Zone-X is a platform where users can monitor defaced websites worldwide, providing a public record of these incidents. This visibility can amplify the impact of their actions and help hacktivists gain recognition within their communities.

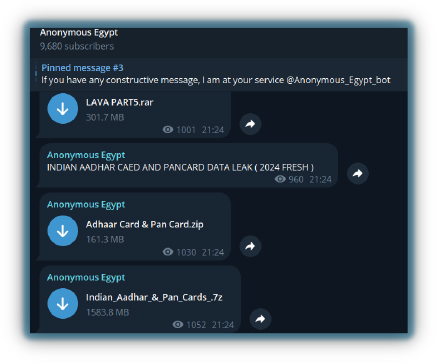

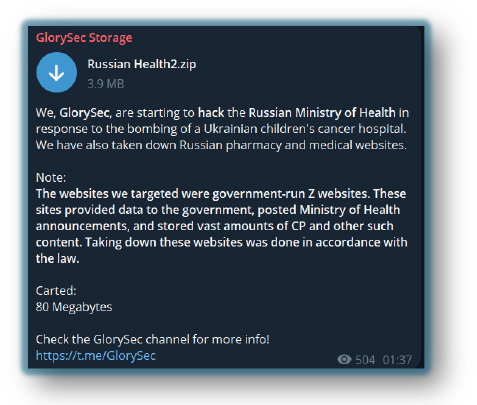

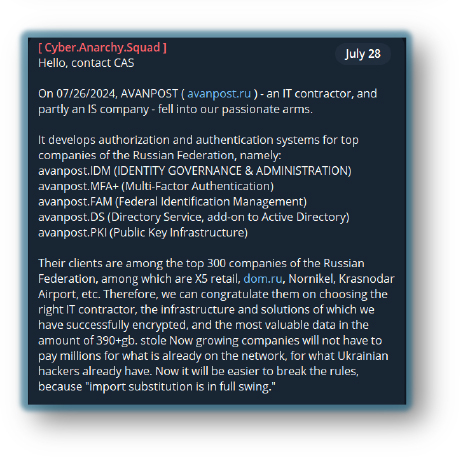

Pro-hacktivists employ a variety of tactics to leak data from adversary countries, using their technical skills to exploit vulnerabilities and amplify their ideological messages.

These groups often target government institutions, corporations, and other organizations to make political statements and protest policies. They use methods such as hacking into databases, breaching network security, and exploiting web vulnerabilities to obtain sensitive information, which they then release to the public.

Additionally, hacktivists sometimes make fake claims, using already leaked data that they modify and share as a new breach to gain attention. However, not all claims are false.

For Example, ‘Glorysec’, leaked data from Russian health organizations, and Cyber Anarchy Squad’ – a pro-Ukraine hacktivist group – leaked data of a Russia-based IT contractor.

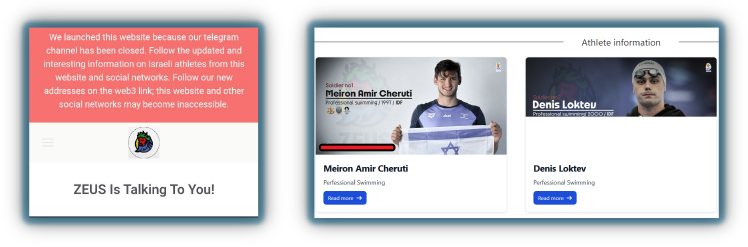

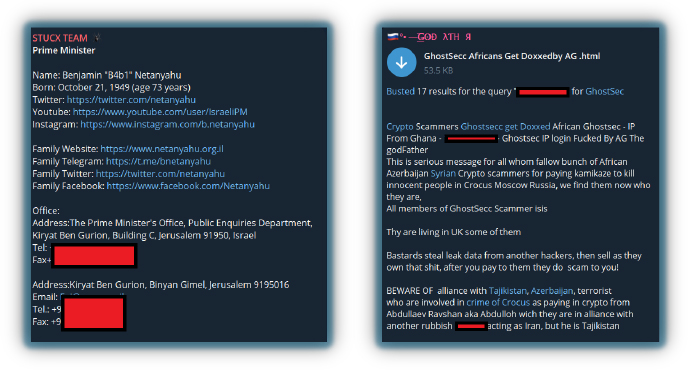

Doxing is the act of publicly revealing someone’s personal identifiable information (PII) without their consent, including phone numbers, email addresses, social media profiles, personal chats, and even data about family and friends. It is often used as an offensive tactic to expose or embarrass individuals, such as political leaders, public figures, or opponents’ hacktivist groups. The intention behind doxing can vary, including harassment, intimidation, or making a political statement.

Hacktivists are increasingly targeting high-profile events, and a new group called ‘Zeus’ released PII information of Israeli athletes participating in the Paris Olympics 2024 on July 30, 2024.

However, the information exposed during doxing is not always accurate or authentic: hacktivists may use a combination of data obtained from previous leaks, information publicly available on the surface web, and Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) techniques to compile their targets’ profiles (and in some cases, they may deliberately include false or misleading information to damage the target’s reputation or sow confusion).

Despite its intended impact, doxing can have serious ethical and legal implications. As a result, it is widely considered one of the more aggressive and controversial tactics employed by hacktivists.

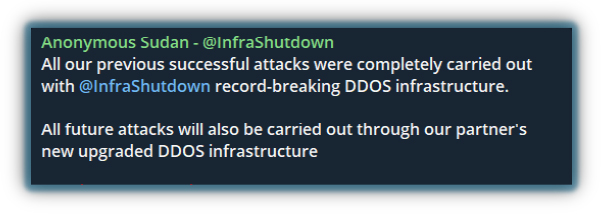

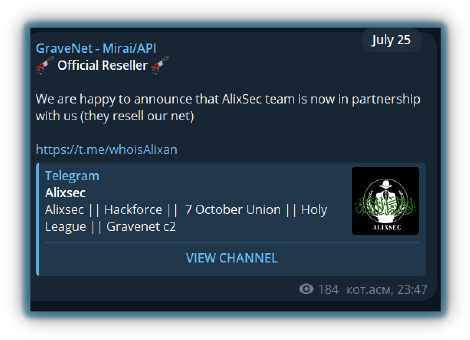

Nowadays, there is a growing trend of global collaboration among hacktivist groups. Pro-Palestinian hacktivists are forming alliances with pro-Russian groups, Indian hacktivists are teaming up with Nepalese groups, and Pakistani hacktivists are collaborating with Bangladeshi counterparts. These alliances can significantly impact their adversaries’ digital infrastructure by coordinating large-scale DDoS attacks, which can cause extended downtimes. Members work side by side to find vulnerabilities, share knowledge, and support each other to increase the rate and effectiveness of their attacks.

Hacktivist groups also partner with DDoS and doxing service providers to manage costs and promote their services, and in exchange, they advertise these tools on hacktivist channels, boosting their visibility.

One major alliance, known as the ‘Holy League’, currently includes over 70+ pro-Russian, pro-Palestinian groups, and a Malaysian group collaborating with Russian groups.

The collaboration among hacktivist groups can significantly impact countries that do not align with their ideologies.

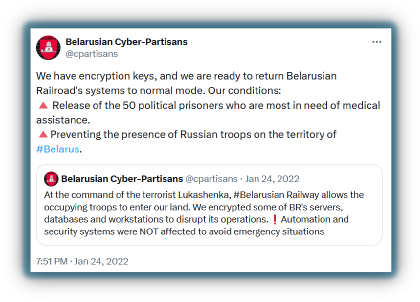

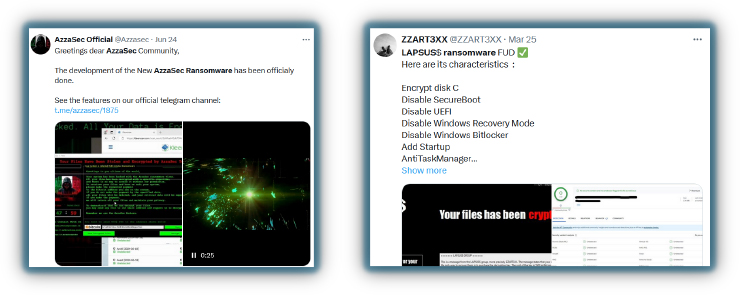

Hacktivist groups have increasingly turned to developing ransomware as a tactic to advance their agendas. While ransomware has traditionally been used for financial gains, some hacktivists employ it for political or ideological purposes.

An example of this occurred in early 2022 when the hacktivist group Belarusian Cyber Partisans encrypted the servers of the Belarusian Railway. Unlike typical ransomware attacks, they did not demand a ransom in crypto. Instead, they demanded the release of prisoners in need of medical attention and the withdrawal of Russian troops from Belarus in exchange for the decryption key.

In modern times, some hacktivists have developed ransomware to earn money while promoting political ideologies. Several groups, such as Azzasec, Cybervolk, and a France-based Lapsus$ group (not to be confused with Arion Kurtaj’s group from 2022), have created their own ransomware variants.

The leaks of ransomware builders like LockBit and Conti’s source code have made it easier for several groups to create ransomware. However, without analysis, it’s difficult to determine whether it comprises of old ransomware source codes or is an entirely new variant. This highlights the evolving nature of hacktivism, where monetary gain and political motivations can intersect.

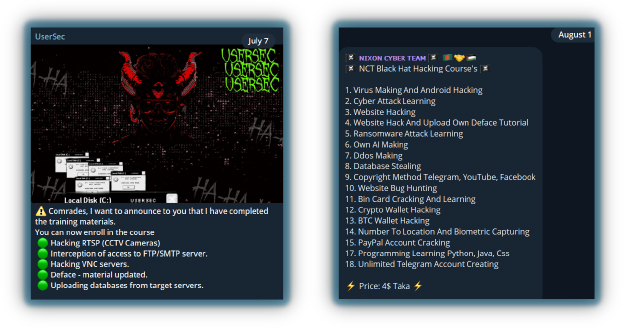

A new trend among hacktivist groups is the creation and sale of training courses that teach offensive hacking techniques and cover a range of topics, including Pen-testing, Web app exploitation, DDoS, and Defacement attacks. By selling these courses, hacktivists generate revenue to support their activities, such as paying for DDoS/stressors subscriptions.

In addition to offering their own courses, hacktivist groups also distribute pirated versions of legitimate courses created by cybersecurity researchers, making these materials accessible for free. They establish chat channels or use platforms like Google Meet to discuss topics and address users’ questions, fostering a community where participants can learn and refine their skills.

This approach allows hacktivist groups to expand their influence and recruit new members while providing a steady income stream to fund their operations. It also poses a challenge as these activities spread potentially harmful knowledge and skills to a wider audience.

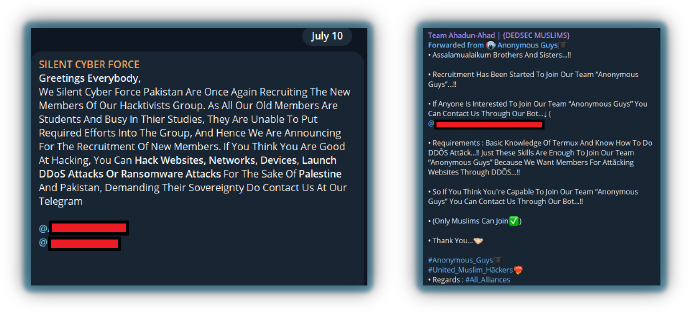

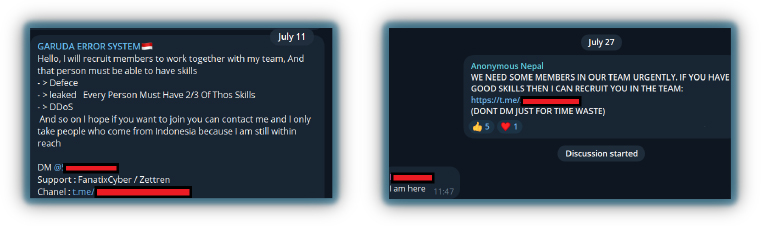

Recruiting new members is essential for hacktivist groups, as they often seek individuals with similar mindsets or religious beliefs. These groups usually don’t offer monetary incentives; instead, they rely on shared ideologies and patriotism against adversary nations.

Many members are young, often between the ages of 16-24, as indicated in groups like Silent Cyber Forces (which has previously referenced that many of its members are occupied with studies). This age demographic is common in hacktivist circles, where members are motivated by nationalism or a desire to act against perceived injustices.

These groups organize DDoS attacks, with more skilled members engaging in web exploitation, defacement, and advanced hacking attacks. Recruitment efforts are aimed at increasing their ranks to apply more pressure on targeted servers and coordinating attacks from multiple regions to maximize impact. By expanding their members, hacktivist groups can enhance their capabilities and execute more widespread attacks.

New recruits need to demonstrate commitment through participation (i.e. in a DDoS attack) or face expulsion from the group. Administrators monitor such activity, as well as share targets for upcoming attacks.

Hacktivist groups use various methods to fund their activities. Monetization efforts which include selling data can be sourced from fresh breaches or copied from previous leaks. Depending on the group’s capabilities, this can be accessed for sale, ransom demands, providing or pirating training courses, and selling DDoS tools or stealer logs.

KillSec ransomware was developed by the Russian-based hacktivist group Killnet and is now being used to extort organizations for payment.

Furthermore, some hacktivist groups maintain private Telegram channels, which require subscriptions for access to exclusive content, where they might sell botnets and scripts for attacking websites. This diverse range of monetization strategies allows hacktivist groups to sustain and expand their operations.

Operation ‘Hamsaupdate’ has been active since early December 2023, where the hacktivist group Handala has been using phishing campaigns to gain access to Israel-based organizations. After breaching the systems, they deploy wipers to destroy data and cause significant disruption. This pro-Palestinian group took advantage of the CrowdStrike BSOD issue to launch targeted phishing campaigns, claiming to have attacked multiple Israeli organizations using their proprietary wiper.

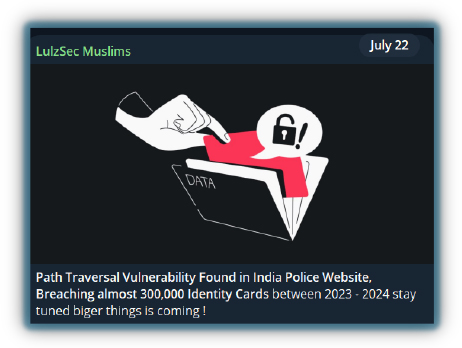

Other hacktivist groups like LulzSec Muslims use various tactics to gain public attention, such as disrupting the Paris Olympic websites. These actions aim to highlight their causes, expressing anger over issues like Israel’s participation in the Olympics, and the perceived disrespect of religious values. Russia-based hacktivists have also carried out DDoS attacks in response to Russia’s ban from the Olympics: by targeting high-profile events, these groups amplify their messages and showcase their opposition to perceived injustices.

Hacktivists are becoming increasingly creative. Instead of simply modifying content or sharing messages on defaced websites, they can now use defacements for profit by locking the webpage of the website (e.g. making a defaced site appear legitimate, luring the public into potential traps).

Additionally, pro-hacktivists leverage data leaks as a powerful tool to challenge their adversaries. Various research reports have also shown that hacktivists are coordinating with advanced persistent threat (APT) groups, working closely with state-backed actors in countries like Russia and Iran.

In conclusion, hacktivists represent a unique and powerful force in the digital landscape, blending activism with hacking to champion the causes they believe in. While their methods can be disruptive and controversial, their actions highlight the growing intersection of technology and social justice, where digital tools are used to challenge authority and promote change. As these digital activists continue to evolve, their influence on global affairs and the impact on their targets cannot be ignored.