The UK faces an escalating cyber threat landscape dominated by sophisticated Russian actors, including state-affiliated groups like Sandworm and APT29, as well as privateer entities operating with Kremlin leniency. These threats have intensified amid geopolitical tensions, targeting critical infrastructure, governmental and defense organizations, and supply chains. Notable campaigns include espionage via spear-phishing, destructive malware like Whispergate, and supply chain compromises, such as SolarWinds. The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) has responded by collaborating with international partners to mitigate over 430 incidents in 2024 alone, reflecting a sharp increase in frequency and severity. Despite these efforts, cyber risks are underestimated, with attackers exploiting systemic vulnerabilities to maximize disruption. Enhanced resilience and coordinated defense measures are crucial to counter these persistent and evolving threats.

The relationship between Britain and Russia is among the most historically rich and dynamic of international pairings, oscillating between profound admiration and strategic antagonism. Initially marked by collaboration, such as their mutual opposition to Napoleon in the early 19th century, their relations soon soured as competition for influence over Central Asia and control of key trade routes reflected the nations’ contrasting priorities: Britain’s maritime empire sought to secure its global trade network and maintain dominance over India, while Russia, a land-based empire, aimed to expand its sphere of influence and secure warm-water ports. This rivalry reached a crescendo during the Crimean War, where Britain and France allied to check Russian expansion. While the war’s famous land battles took place on the Crimean Peninsula, Britain’s decisive naval operations in the Baltic highlighted the disparity between the nations’ military strengths, cementing Britain’s position as a dominant maritime power.

These geopolitical tensions were paralleled by cultural exchanges that deepened mutual fascination. Britain’s reputation for fairness, legal protections, and social refinement attracted Russian intellectuals and aristocrats, many of whom lamented their own country’s autocratic structures. Yet admiration was tempered by skepticism, as Britain’s global ambitions were often viewed as duplicitous and self-serving.

On the British side, Russia’s enigmatic image loomed large in literature, theater, and public discourse. The cultural depictions often reflected broader geopolitical realities: Russia was both a vast, powerful land and an unpredictable rival. Russia sought British expertise in industrial modernity, but rejected British political ideals, dismissing British-style constitutional governance as incompatible with Russia’s largely autocratic traditions.

The Industrial Revolution further entwined the two nations. British entrepreneurs, such as John Hughes, played pivotal roles in Russia’s industrial development, establishing metallurgical centers that laid the foundation for modern Russian industries, many of which are nowadays located in the contested territories in Ukraine.

Comtemporary Russian state propaganda continues to vilify Britain as a shadowy antagonist, orchestrating the “Western conspiracy to contain Russia”, and the current strain on relations – driven by Putin’s neo-imperialist policies – has brought these historical tensions to a head. Unlike previous centuries, however, today’s Russia has one more domain to execute statecraft in: the cyber domain.

Since the beginning of the Russian war in Ukraine in 2022, the UK government has issued numerous warnings about a significant increase in cyber-espionage activity targeting government departments, critical infrastructure, and businesses. The NCSC attributed these attacks to a range of state-sponsored actors, including Russia. The attacks involved various tactics, such as phishing emails, malicious software, and network intrusions, aimed at stealing sensitive information and disrupting operations.

At the same time, NATO member states have experienced a surge in physical attacks targeting critical infrastructure. Civilian facilities like shopping malls and factories have been set ablaze, while vital rail lines in Sweden, Germany, and France have been sabotaged. Defense plants supporting Ukraine have also been hit, including a London aid warehouse in March 2024 and a Welsh ammunition factory in April. The recent news on a suspected Russian plot to bomb a plane at a DHL facility in Birmingham in July has backed up intelligence assessments that the blast was strong enough to have brought down a cargo plane.

This wave of sabotage is arguably the most significant the West has faced since World War II. While Russia maintains plausible deniability (towards which goal it also employs privateering cyber criminals), Western officials increasingly believe the Kremlin is orchestrating many of these attacks. Governments and NATO leaders have publicly blamed Russian intelligence agencies and affiliated groups, implementing various measures to counter this threat.

In response to Western intelligence officers’ expulsions and technological advancements, the Kremlin has embraced a dangerous new ‘gig economy’ model for sabotage, turning to digital tools to recruit a new generation of agents-saboteurs. This model allows Russia to tap into a flexible online workforce for short-term, high-risk missions and supplement the overtaxed intelligence agencies in cyber-attacks on British and Western territory.

Richard Moore, head of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) has repeatedly accused Russia of waging a “staggeringly reckless campaign” of sabotage in Europe while also stepping up its nuclear sabre-rattling and repeated cyber attacks to scare other countries off from backing Ukraine in her defence from Russian aggression.

These assessments were recently echoed by Security Service (MI5) Director General Ken McCallum (UK domestic counterintelligence chief), who said that Russia’s GRU military intelligence service was seeking to cause “mayhem on British and European streets”. Sources familiar with European intelligence have told CYFIRMA analysts that Moscow is likely to step up its campaign against European targets to increase pressure on the West over its support for Kyiv to advance its position before Donald Trump takes the rein of the White House in the United States by late January.

In 2023, the UK government announced that it had disrupted a Russian hacking group targeting critical national infrastructure. The group, known as “Sandworm,” was responsible for a series of destructive cyber-attacks, including the NotPetya ransomware attack in 2017, which caused billions of dollars in damage worldwide.

At the same time, Calisto (aka Star Blizzard), a Russian government-affiliated threat actor was using spear-phishing tactics to compromise individual email accounts belonging to high-level politicians and their aides for espionage purposes. The group has previously used this tactic in other NATO countries and has been known for targeting academia, the defence industry, governmental organisations, and NGOs and also for employing leaks of stolen emails as part of Russia’s information-warfare efforts.

The UK government’s counter-action involved working with international partners to disrupt the group’s operations and prevent future attacks, but the Russian attacks have only reached a crescendo since that time. Richard Horne, head of the NCSC, recently urged both government and businesses to strengthen their cyber defenses.

“Hostile activity in UK cyberspace has increased in frequency, sophistication, and intensity. Actors are increasingly using our technology dependence against us, seeking to cause maximum disruption and destruction. With our partners, including at the NPSA, we can see how cyber attacks are increasingly important to Russian actors, along with sabotage threats to physical security, which the director general of MI5 spoke about recently. And yet, despite all this, we believe the severity of the risk facing the UK is being widely underestimated.”

In 2024, conflicts have driven a volatile cyber threat landscape, with Russia’s deployment of destructive malware against Ukrainian targets and frequent attempts to disrupt NATO countries, particularly the UK, in support of its war effort. By early December, NCSC’s Incident Management team had managed 430 incidents, a notable increase from 371 in the previous year.

In September, the NCSC, alongside agencies from the US, Netherlands, Czech Republic, Germany, Estonia, Latvia, Canada, Australia, and Ukraine, exposed the methods used by Unit 29155 of Russia’s GRU to execute cyber operations.

In the UK, this GRU unit targeted organizations to gather intelligence, damage reputations through the theft and leaking of sensitive data, deface websites, and sabotage systems by destroying data, with the primary objective to undermie efforts to aid Ukraine. The unit was also responsible for deploying Whispergate malware across Ukraine before Russia’s 2022 invasion. Their operations often involve non-GRU actors, including cybercriminals and enablers.

Simultaneously, cyber threat actors linked to Russia’s SVR, or military intelligence, have been particularly active, exploiting vulnerabilities at scale as part of a global campaign. Known as APT29, these actors target two main victim groups: “targets of opportunity” and “targets of intent.” Targets of opportunity are identified through mass scanning of internet-facing systems with unpatched vulnerabilities, making any organization with such weaknesses a potential victim.

For both victim groups, once access is gained, SVR actors conduct further operations, such as leveraging compromised accounts or moving laterally to connected networks, including those in supply chains. Intentional targets include government and diplomatic entities, think tanks, tech firms, and financial institutions. Recently, their scope has expanded to aviation, education, law enforcement, local councils, government financial departments, and military organizations.

Notable operations attributed to SVR actors include the 2020 SolarWinds supply chain compromise and targeting entities involved in developing the COVID-19 vaccine that same year.

Beyond these high-profile incidents, Russian-linked cyberattacks have continued to strike a wide array of UK organizations, including government bodies, businesses, and academic institutions. These attacks often employ advanced techniques, such as spear-phishing, watering hole attacks, and zero-day exploits, underscoring the increasing sophistication and persistent threat posed by cyber adversaries.

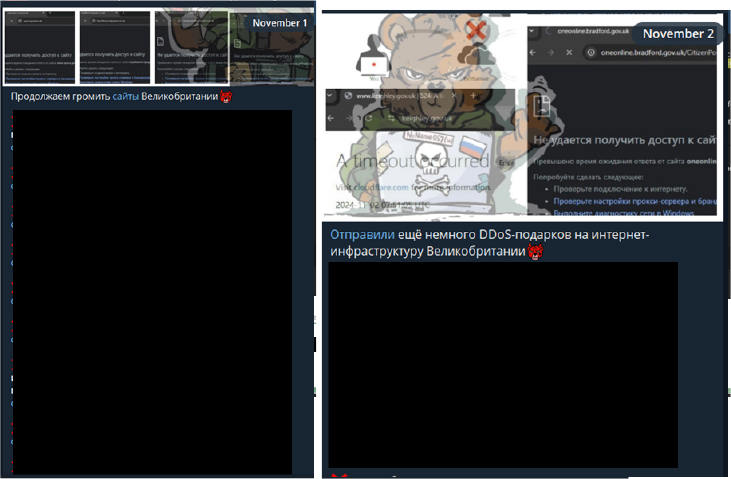

Since September, Noname057(16), a well-known Russian hacktivist group, has been actively targeting the United Kingdom’s cyberspace. On November 1, 2024, the group launched DDoS attacks against various financial and banking institutions across the UK. The following day, November 2, 2024, they carried out another attack, this time targeting West Atlantic, a UK-based entity.

On November 28, 2024, DXPLOIT, a pro-Palestinian hacktivist group, launched an attack on a UK-based website. Shortly after, OVERFLAME, a Russian hacktivist group, reshared the attack details in their Telegram channel. Notably, there has been significant collaboration between pro-Palestinian and Russian hacktivist groups, as both share a common opposition to Israel. These groups frequently exchange resources and tools and carry out joint attacks, amplifying the impact and causing disruption.

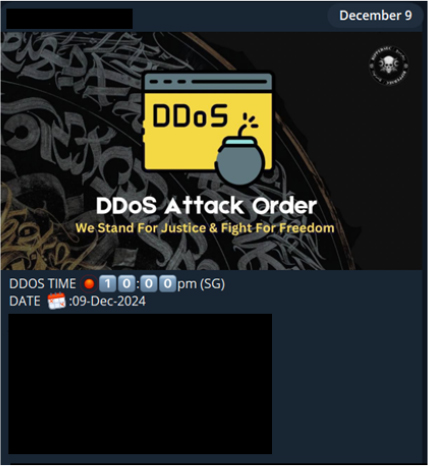

During our investigation into multiple hacktivist groups targeting the United Kingdom, we discovered a common trend: these groups are coordinating their attacks on UK cyberspace under the banner of #OpUK.

In recent years, the UK has faced a surge in cyber-attacks. While definitive attribution remains complex, the sophistication of these attacks and the backdrop of geopolitical tensions strongly indicate Russian involvement.

These attacks have targeted diverse organizations, causing widespread disruption and financial losses. Russia has solidified its position as a capable, motivated, and irresponsible cyber threat actor. Russian operatives have almost certainly escalated their cyber campaigns against Ukraine and its allies, aligning these operations with their military objectives and broader geopolitical ambitions.

Strained by the demands of an all-out war against Ukraine, Russia has increasingly outsourced cyber operations to privateers and other non-state actors. These groups, often beyond direct state control, introduce a heightened unpredictability to their activities. This trend is likely to persist, as the Kremlin grants these actors greater latitude. From Moscow’s perspective, fostering global instability serves to divert attention from its aggression in Ukraine, further stretching the resources of those who oppose it.