Despite the region’s superficial media image as a region where religious fanaticism takes primacy in the political landscape, in fact it’s plain geopolitics which takes primacy over religious matters virtually all the time. We can even say the Middle East is the world’s hotbed of geopolitics and as such, global geopolitical trends tend to manifest themselves early in the region. The inevitable process of digitization of Middle Eastern economies brings with it a growing exposure to the risk of cyber attacks, as political adversaries increasingly seek to exploit opportunities in cyber-enabled vulnerabilities that have the potential to diminish an opponent’s economic and military power. The cyber realm has been taking the form of the vanguard of geopolitical statecraft with the Middle East serving as the hotbed of both geopolitics and subsequently innovation and use of cyber intelligence collection, cyber warfare and integration of cyber warfare with kinetic means of conflict.

The Middle East is a region rife with conflict. It‘s political map is very complex, as are the relationships of its peoples, with identities transcending national borders. Local tensions are further exacerbated by the specific nature of its resource-based economies (i.e. its international importance as a hydrocarbon energy hub); strong population growth, and the clash of modernity with traditional cultural norms. However, despite its superficial media image as a region where religious fanaticism takes primacy in the political landscape, we are able to decipher its political map, using traditional geopolitical analysis. In fact, despite the media image, in the Middle East geopolitics takes primacy over religious matters virtually all the time. We can even say the Middle East is the world’s hotbed of geopolitics.

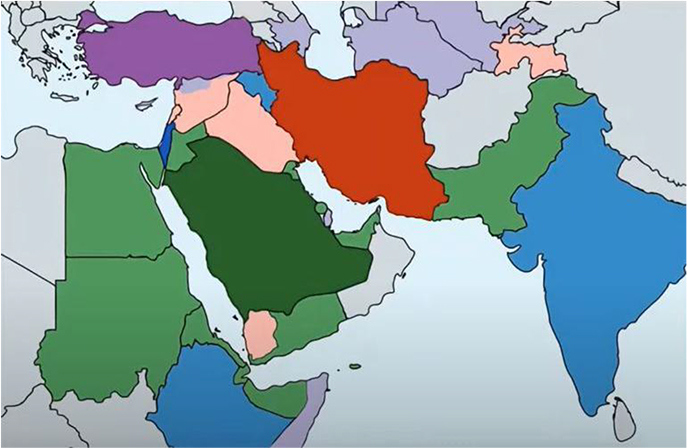

To focus our analysis, this reports splits the region into four regional powers; Saudi Arabia, Iran, Israel and Turkey, each nation commanding their own alliances to help them secure their interests. Arguably the main axis of conflict lies between Saudi Arabia and Iran: both countries implement elements of theocracy in their systems of government, and, while Saudi Arabia is the leading power amongst Sunni Islam countries (a role contested by Turkey), Iran is the leading country for the Shīʿa minority, with a greater than 90% Shīʿīte population. In Iraq, the internal division between its Shīʿa majority and Sunni minority has been bloody, Azerbaijan, for instance, where religious observance varies, its Shīʿa majority population is not aligned with Iran, but with Sunni Turkey because of shared ethnic, cultural and language affinity. Shīʿītes also comprise the majority of citizens in Bahrain, however, the government is largely Sunni, and allies itself with the Saudi-led bloc.

So whilst language, culture, and ethnicity can sometimes trump the Sunni/ Shīʿa divide, elsewhere it is sufficient for Iran to adopt a paternalistic approach towards its Shīʿa populations, trying to enlist local groups to work in their political interest. Examples of this include Syria, (where the ‘Alawite‘ sect has only recently been legitimized by the Shīʿa branch for political purposes); the politically powerful Hezbollah militia in Lebanon, or the Ansar Allah rebels in Yemen, colloquially known as Houthis. Iran uses Shīʿa groups and militias such as these to gain an advantage in internal Middle Eastern politics, also providing direct and indirect military support to armed groups, and partaking in civil wars to attempt to destabilize the influence of the Sunni coalition led by Saudi Arabia. Both Iran and Saudi Arabia have sought to gain leverage over one another using methods short of war: backing regional proxies, amplifying internal opposition and increasingly by employing cyber warfare, to the extent that it could even be described as a proxy war.

While Iran is hostile to all other blocs in the region, its relationship with Israel is particularly thorny; with the latter being restrained by the United States from preventive military strike on Iran’s nuclear programme. The United States were able to persuade Israel to join an American cyber warfare operation against the Natanz facility instead, but given the internal political dynamics of all three countries, a new spiraling of violence between Israel and Iran in the near future is not unlikely. Israel, though without official allies in the region since its inception, can rely on good relationships with the Kurdish autonomous region in northern Iraq, Ethiopia, India,and the Saudi-led bloc of Egypt, Jordan, the UAE and Saudi Arabia itself, all of which see Iran as their common enemy, and the region’s primary threat.

Saudi Arabia is the predominant Sunni power, no doubt enabled by the possession of the World’s most accessible oil reserves. Its internal politics have been dominated by the relationship of two families, the ruling House of Saud, and the Al ash-Sheikh family, which traces its origins to 18th century religious leader; Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. He is synomymous for a fundamentalist and revivalist strain of Islam – Wahhabism – which the House of Saud has promised to promote in exchange for political legitimacy to rule all the diverse tribes of the country. The height of power of the Wahhabist clerical class came during the oil crisis in the 1970s, culminating after the siege of Mecca in 1979, and the Soviet Afghan war. Hundreds of millions of petrodollars were funneled into various ‚salafi‘ – that is to say, Islamically conservative – institutions across globe (including in Western countries) that helped to shift global Islamic communities towards a very traditional interpretation of Islam. This gave rise to various Islamist movements (such as Islamic State) that changed the political landscape of entire regions. Pakistan is a good example of this, but even in the formerly very secular Turkey, the hijab as a symbol of religious conservatism is making a comeback.

This trajectory destabilised when certain Islamist movements started engaging in international terrorism. This put great pressure on the House of Saud, which relies on the United States for its security, and is ultimately why al-Qaeda and their related organizations sought deposition of the House of Saud in favour of a caliphate; a goal later transmuted and undertaken by ISIS in Syria. Since 9/11, the House of Saud has been on a steady campaign to crack the power of the fundamentalist clerics and distance itself from the terrorist organizations, which culminated with the Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman (MBS) taking over leadership of the country. He is attempting to reshape its oil-dependent economy. However, this goes hand in hand with a certain degree of liberalization and substantial diminishing of clerical power, all of which is taking Saudi Arabia to new territory.

The Saudi security guarantor and major Middle Eastern power broker – the USA – are on a trajectory to become net exporter of energy. As such, they are openly trying to diminish their ties to the region in order to focus on South East Asia and competition with China, which leads the Sunni coalition more open in its competition with Iran. Reputational damage sustained after the state-sanctioned assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, weak US reaction to Houthi attacks on Saudi oil installations, and a potential resurgence of American isolationism might make Saudi Arabia appear vulnerable to Iran, which in turn hopes to negotiate a new nuclear deal with the USA under Biden. If successful, it would lift the highly punitive US sanctions, which would significantly boost the Iranian military budget and may intensfy Iranian attacks on Saudi positions in the region, in which cyberspace will be an increasingly important battlefield.

Before the ascent of the (partly Islamist) AKP government to power in 2002, Turkey – a constitutionally secular state – had maintained a neutral foreign policy with regards to the religious and sectarian conflicts in the region. Under Erdoğan’s leadership, Turkey has turned away from Europe and focused on neo-ottoman pretensions, engaging in a variety of diplomatic and military offensives, most notably by taking Qatar under its protection in its diplomatic conflict with Saudi Arabia by engaging militarily in Syria. This and numerous other policies put Turkey in diplomatic conflict with Russia, Saudi Arabia and its allies (most notably Egypt), Greece, and Iran. With both Turkey and Iran‘s differing geopolitical goals in Syria and Iraq, have led to increased tensions, which worsened after the start of the civil war in Yemen factions.

This – by no means exhaustive – overview of the Middle Eastern geopolitical situation should raise global awareness that conflict will be a norm in the region in the coming decades, notwithstanding civil strife in populous but poverty stricken countries that will have trouble accommodating surges in food prices due to inflationary pressures and complications stemming from Russian aggression in Ukraine (for instance Somalia, Lebanon, and Egypt, the latter of which is registered for bread rationing).

Due to drastic shifts in cyber interconnectedness and electronic high-tech infrastructure in the region, cyberspace is now being closely integrated into domains of statecraft and war.

In light of emerging cyber security challenges, most states are forced to rethink their strategic calculus with regard to kinetic and non-kinetic threats to critical national infrastructure, sensitive information security, and signal intelligence. Cyberspace is quickly becoming the frontier on which the strategic competition between states (and non-state actors) plays out first and foremost. All regional powers are heavily investing in building cyber capabilities that would enable them to achieve their geopolitical goals or offer them a diplomatic edge over their adversaries. There are no borders in cyberspace, and cyber campaigns play out globally, affecting numerous stakeholders.

We thus absolutely cannot afford to ignore the role of outside powers in the Middle Eastern cyber domain. Take China, for example: China is heavily dependent on the region, which is responsible for roughly half of China’s oil imports, and it‘s reliance on Middle Eastern oil is only likely to increase with projections doubling by the mid-2030s. As the experience from Africa shows, China can be particularly hard-nosed when it comes to securing it‘s raw material or energy needs, and with it‘s goal to become world’s foremost provider of telecommunication systems, we can be certain China will seek to gain primacy by any means necessary. Chinese cyber warfare programs are more centered on fostering offensive capabilities compared to other players in the cyber domain, while clandestine data collection and industrial espionage are now synonymous with China. The nation‘s footprint in the region is arguably expected to grow, especially given their opening of a first military base in Djibouti.

Another crucial role in the cyber domain is played by the United States. We should assume the US military – as the financier that enabled the rise of the internet – has always invested in cyber warfare, with reports of successful weaponizing of cyberspace dating back to the Reagan era, when a US-planted trojan caused a major explosion of the Soviet Trans-Siberian gas pipeline in summer of 1982.

Under presidents Bush Jr. and Obama, cyber operations came to the forefront, mainly with the US targeting of Iran. American cyber defense spending hit a historic peak of $4.7 billion USD in Obama’s 2014 budget, more than a wealthy European economy‘s overall defense spend. By spring 2010, the U.S. Strategic Command’s Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM) achieved initial operational capability, and the same year the Stuxnet malware broke in the news. While neither US or Israeli governments acknowledged authoring of the cyber weapon, it is widely accepted that the malware was co-created to attack Iran’s military nuclear programme under operation code-named Olympic games. It is also accepted that the programme was inherited and accelerated by the Obama administration, as the US was at pains to restrain Israel from attacking Iran’s nuclear facilities with conventional weapons.

At the very moment, the US is engaging in what we could term undeclared (and underreported) cyber war with Iran, with near constant reciprocal attacks. It is assumed, the Obama administration accelerated operation ‘Nitro Zeus‘, an alternative plan to full-scale war with Iran, should the JCPOA negotiations fall through, in which the US is believed to have planted a myriad of time bombs in key Iranian infrastructure, including air defenses, the electrical grid, communications systems, water treatment facilities, and other key assets.

Iran, however, should not be viewed as a hapless victim but an emerging cyber power, with analysts warning of Iranian retaliation in kind. Their capability is assumed as it has been linked with countless cyber attacks in the US, Saudi Arabia, and Israel. Cyber analysts were able to identify no less than 7 Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) teams working with both Iranian Intelligence and the Revolutionary Guards, their initial vector of attack often using spearphishing, social engineering or social media phishing, targeting energy companies, petrochemical and heavy industries, the finance sector, aviation, or infrastructure grids. Their most prominent attack so far occurred in August 2012, where tens of thousands of Saudi Aramco and RasGas computers were destroyed in a sophisticated Shamoon wiper attack that were likely built on techniques used against Iran just months prior. Cyber threat activity is a constant between Iran on one hand and Israel, US, Saudi Arabia and its clients on the other.

Each heating of the tensions in diplomatic relations between these sides has seen a spiraling of cyber activity, for example US withdrawal from the nuclear deal or the deadly attack on the Iranian general; Qasem Soleimani, saw tremendous spikes in cyber attacks on the US, Israel and Saudi Arabia coming from Iran. Iran doesn’t stop at intelligence collection or attacking key infrastructure, as it has been demonstrating capacity to also use criminal tactics often deployed by Russia like the use of ransomware to strike at its rivals’ commercial interests from inside.

Furthermore, electronic warfare is becoming an integral element of all military branches but especially in modern air forces, building a closer relationship with cyber warfare. In 2011, Iran demonstrated advanced electronic warfare capability by commandeering a US RQ-170 Sentinel drone and landing it safely. Iran was able to reverse engineer numerous components of the drone and was able to produce a small fleet of copycat vehicles, which were found to be quite advanced and emulating western technology after one of them was shot down by Israeli military in Syria in 2018.

The rise of Iran in the cyber realm in combination with thousands of years of use of clandestine capabilities in the Persian imperial project has led its rivals in the region to step up significantly in recent years to improve their security posture in the face of mounting cyber threats. Israel has been a technological superpower for decades with Saudi Arabia and UAE increasingly partnering with the Jewish state to receive their latest cyber measures available. Indeed, the perceived threat from Iran has helped the traditionally hostile Gulf monarchies build security ties with Israel and the cyber realm has been spearheading this development. With the situation, it is possible that a degree of cooperation in offensive cyber action against Iran exists between the Israel and Saudi-led blocks. While Iran – thanks to its pariah status – has had to rely mostly on homegrown cyber development (with limited help from Russia and China), Saudi Arabia has outsourced bespoke tools to private contractors from countries like the United States, United Kingdom or Israel.

It is a public secret that Israel and Iran are engaging in a covert war, consisting of sabotage, cyber attacks as well as unacknowledged kinetic strikes. Iran has carried out numerous cyberattacks against Israel over the years, including a massive hack aimed at disrupting Israel’s water supply in July 2020. Israel has long conducted sabotage and covert campaigns against Iranian targets in Lebanon, Syria and Iraq, as well as within Iran itself. Inside Iran, Israel typically uses on-the-ground assets to sabotage sites related to Iran’s military and nuclear program, as it did in November 2020 when Israel used a remotely controlled robot to assassinate Iran’s chief nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizad.

Regardless of the outcome of the West’s negotiations with Iran over its nuclear program, Iran and Israel will likely continue to tactically escalate their covert campaigns against one another. Israel and Saudi Arabia are likely to employ all their might including cyber warfare to degrade and diminish Iranian military capacity, mainly focusing on the nuclear, missile and drone programmes. Since the expected results of the new Iran nuclear deal are not likely to fully address Israeli and Saudi security concerns, the high risk of escalation in tactical exchanges is likely to spill over to countries with friendly ties to Israel and Saudi Arabia in the cyber realm, both inside and outside the region. Oil-dependent Iraqi Kurdistan, Bahrain and the UAE will likely be the primary targets outside of Israel.

Not to be left behind, Turkish government officials also made comments about establishing a “hacker army”. While the comments expressed a need to build a defensive capacity, it would be extremely naive to think Turkey is not heavily investing in offensive capabilities as well. Turkey has an imperial tradition going down centuries, with projection of military power being at the epicenter of Turkish strategic culture, using offensive capacity to back diplomatic efforts. Turkey has the ambition of becoming yet again the predominant regional force and in accordance with its culture is investing heavily with military expenditure as a share of GDP being roughly double the European standard, post-Cold War. It has become apparent that the Turkish government has lately fully embraced cyber warfare and espionage as a important tenet of strategic statecraft, with numerous reports of sweeping cyberattacks targeting governments and other organizations in Europe and the Middle East believed to be the work of state-backed hackers acting in the interests of the Turkish government surfacing in recent years. Besides actively engaging in cyber operations, Turkey is also an attractive target for other powers in the region and beyond. Besides it‘s ongoing military engagement opposing Syrian government and Kurdish autonomy, Turkey has been a key ally to Azerbaijan to a degree where it’s widely believed, the Azeri campaign conquest of Nagorno Karabakh had been orchestrated by the Turkish government. This makes Turkey a target for Armenian and Russian retribution. Turkey’s position as a key armaments provider to Ukraine in its defense from Russian aggression is also making Turkish military industrial complex target number one for cyber operations coming from Russia; the world’s leading power when it comes to using cyber warfare, espionage and weaponizing criminal structures in cyberspace. This situation is being compounded by the fact that Russia and Turkey are at odds with each other in the Syrian war.

Even without the two wars, the growing role of the armaments sector in the Turkish economy and its increasingly assertive diplomatic conduct would inevitably draw the attention of other regional powers and their cyber units. For another example, Turkey has taken on the role of Qatar’s protector, while it’s under blockade and diplomatic siege by the Saudi-led block, which is likely having consequences in the cyber realm.

In the Middle East, global geopolitical trends tend to manifest themselves early, and intensely. The inevitable process of digitization of Middle Eastern economies brings with it a growing exposure to the risk of cyber attacks, as political adversaries increasingly seek to exploit opportunities in cyber-enabled vulnerabilities that have the potential to diminish an opponent’s economic and military power.

The cyber realm has been taking the form of the vanguard of geopolitical statecraft with the Middle East serving as the hotbed of both geopolitics and subsequently innovation and use of cyber intelligence collection, cyber warfare and integration of cyber warfare with kinetic means of conflict. Over the recent years, states (and non-state actors) in the region have gone to great lengths to build defensive and offensive capabilities.

The increasing use of cyber warfare for geopolitical aims is likely to play a key role in the unraveling of an already unstable, conflict-infested part of the world. Cyber-enabled geopolitics will shape the relationship between Iran and its neighbors; and allies of both sides, in particular the United States, Saudi Arabia and Israel are bound to play a central role in this geopolitical confrontation.

The intensification of the cyber arms race in the Middle East offers valuable lessons for all governments in the world, regardless of their alignment, polity or size of their economy. For no state in the world is it a question of if espionage, sabotage, and social engineering are slipping undetected into their computer networks, but rather how to implement sufficient cyber defense and whether to invest in offensive capability.

1 His father, king Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud is still de jure the leader of the country, but de facto it’s MBS who should be considered the ruler at the moment.

2After Donald Trump’s administration walked away from JCPOA and imposed sanctions on Iran, the immediate cost to Iran has been as much as one third of its GDP. Many commentators fear that after a new deal, Iran would use much of these re-gained funds in military buildup and offensive actions in the region.

3The biggest oil company in the world, owned by the Saudi government.

4Persia has been an intelligence superpower at least since the days of the Achaemenid Empire, more than five centuries before Christ.

5To give an example, Turkish air force is older than the republic, Turkish navy is older than the Ottoman empire and Turkish land forces are older than Islam or Christianity.

6While diplomacy is perceived by the wide public as the art of maintaining peaceful relationships between nations, its actual mission is compelling other parties to do what they otherwise wouldn’t on their own.