Ukraine has famously some of the best farmland in the world, and before the invasion, Russia and Ukraine combined accounted for approximately 12% of all calories that make it onto the global market. The figure for specific crops were even more dramatic: Ukraine accounted for around half of all global sunflower oil exports, and between 2018 and 2020 it’s reported that ~44% of all African wheat imports came from either Russia or Ukraine. After Russia attacked Ukraine in 2022, the UN together with Turkey have been able to broker a deal under which Ukraine could continue to export its foodstuffs to global markets via its Black Sea ports. However, Russia pulled out of the Black Sea Grain Initiative this summer, bombarding Ukraine’s sea ports and grain export terminals with the aim to damage the Ukrainian economy as well as European political cohesion. We assess that Russia will also use cyber tools to target European agricultural logistics to keep pressure on the Western alliance supporting Ukraine.

This summer, Russia pulled out of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, a Turkish- and United Nations-brokered wartime agreement to ensure the safe passage of grain from Ukrainian ports on the Black Sea. Ukraine is one of the world’s top producers of grain, but after Russia invaded in February 2022, more than 20 million tons of it were trapped in the country’s Black Sea ports. Under the agreement, more than 33 million tons of grain were shipped out of Ukraine, the majority of it to developing countries. Since the deal expired, however, Russia has repeatedly attacked both Ukraine’s grain supply and ports, destroying an estimated 60 thousand tons of grain and putting global food supply at risk.

The collapse of the pact that allowed Ukraine to export more than 30 million tons of grain to some of the world’s hungriest nations both threatens global food supplies and casts doubt on Turkish President; Erdoğan’s, much-touted influence over Putin, which he arguably earned following his refusal to join NATO allies in sanctioning Russia. Russia’s withdrawal comes as the recently re-elected Erdogan pivots back to Turkey’s Western allies, looking for ways out of a painful economic crisis. Erdogan and other world leaders are scrambling to salvage the deal, but Putin is digging in his heels. As always, it’s the world’s neediest who will suffer most: the International Monetary Fund predicts global food costs will jump, and the U.N. (whose food program sourced 80% of its grain from Ukraine under the deal) has warned that “many may die.” Russia has since targeted Ukraine Black Sea ports with missile strikes and is likely to implement cyber means to try to interdict or obstruct Ukraine’s agricultural exports via EU logistical chains.

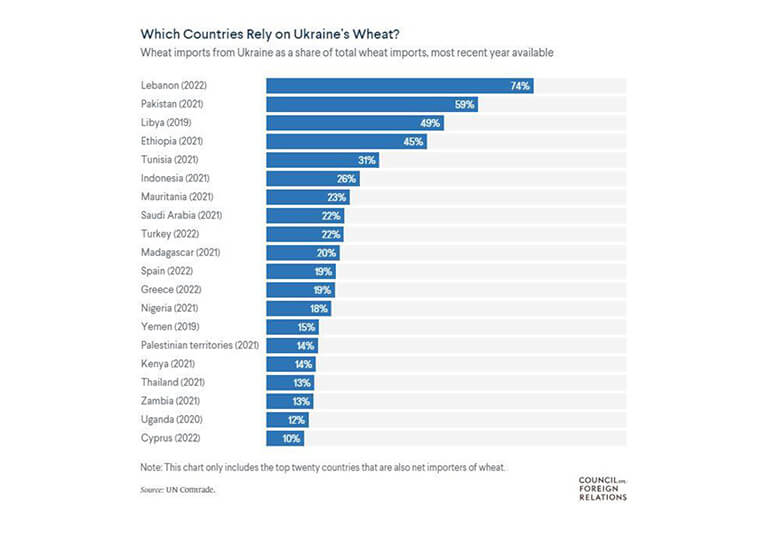

Ukraine produces about 10% of the world’s wheat and 15% of its corn, counting multiple countries in Africa and the Middle East among its top buyers. Many destinations for Ukrainian grain are lower-income nations already grappling with food insecurity, and some, such as Lebanon and Pakistan, are also suffering political and economic crises, and others, such as Indonesia and Nigeria, have huge populations to feed. Prior to Russia’s invasion, Ukraine exported approximately 90% of its agricultural products via its Black Sea ports.

The deal intended to secure the safe transportation of grain and foodstuffs from Ukrainian ports (BGSI, or the Black Sea Grain Initiative) was the agreement between by the United Nations and Turkey that allowed tens of millions of tons of Ukrainian agricultural exports to make their way onto global markets through Ukrainian Black Sea ports, despite the war going on with Russia – which includes many skirmishes in the Black Sea. Under a separate memorandum of understanding between the Russia and the UN Secretariat, Russia reiterated its intention to facilitate the unimpeded export of agricultural products from Ukrainian ports, and the UN Secretariat agreed to facilitate the export of raw materials needed to produce fertilizers, namely ammonia, from Russia to world markets.

The agreement was signed in July 2022, and the first ships left Ukrainian ports weeks later. Until its termination, ships made over a thousand voyages from three of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports, exporting over 30 million metric tons of Ukrainian-produced corn, wheat, sunflower seeds and oil, barley, rapeseed, soybeans, and other products. These foodstuffs were imported by 45 countries around the world, but the impacts of the deal were global, helping to ease global grain prices that had hit an all-time high in March 2022 in response to the Russian invasion. That level of crop inflation was even higher than that which contributed to the Arab Spring, with devastating consequences for Syria and the whole region.

Russia was trying to use the BGSI as leverage for Western concessions that included reconnecting its State Agricultural Bank into Western dollar payment system SWIFT, a deal that would have further weakened the already leaky Western sanctions regime. While Russia is actively seeking diplomatic support in the global south – among countries that often rely on Ukrainian grain – Moscow arguably realized the political benefit from leaving the deal.

By forcing Ukraine to seek alternative transportation for its agricultural products, Russia coerces the European Union to manage market volatility caused by Ukraine’s shifting export routes. As Ukraine increased the volume of grain it exported by land, the glut of Ukrainian grain in neighboring countries caused prices to plummet, and sparked farmer protests in Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria in early 2023. By May 2023, the EU had approved measures by these countries to ban the import of Ukrainian wheat, maize, rapeseed, and sunflower seed into their countries, while still facilitating the transport of these products. A Ukraine reliant on alternative export routes continues to put financial pressure on the EU to support farmers, as well as political pressure to extend its “exceptional and temporary” trade measures, threatening unified EU support for Ukraine. Russia has also stolen nearly 6 million metric tons of Ukrainian wheat and sold it as Russia-produced grains in the global markets.

Russia’s actions in the global grain market have not only created economic hardship for Ukraine and its neighboring countries but also exposed potential cyber vulnerabilities. As Ukraine seeks alternative export routes, its reliance on digital infrastructure for managing logistics and financial transactions increases, making it a more attractive target for cyberattacks.

With these calculated attacks, Russia made clear that it sought not only a stoppage to Ukraine’s agricultural exports through Black Sea ports belonging to Ukraine, but the termination of its agricultural export writ large.

Nonetheless, Ukraine continues to seek alternative routes for its agricultural products with the help of the EU and other allies. As of September, a temporary humanitarian corridor has seen the safe passage of numerous vessels trapped in Ukraine’s ports, since the invasion began, but its capacity is incomparable to peacetime traffic. Progress has also been announced along European Union solidarity lanes, in which the Croatian and Romanian prime ministers agreed to increase Ukraine’s exports through their own infrastructure, allowing Romania to transport 60% of Ukraine’s agricultural exports (with potential to double the volume in coming years). While Russia would not risk confrontation with NATO by overt kinetic attacks, this places a large target on the backs of logistical infrastructure companies which will likely face attack from Russian hackers.

Russia has already tried to interfere with maritime traffic by targeting Lloyd’s of London; the biggest maritime insurance marketplace in the world. The company is a prominent supporter of sanctions against Russia and is the irreplaceable hub for maritime shipping insurance, without which Ukraine is unable to export its foodstuffs to the world market, making it a prime cyber target for Russian APTs

Prior to Russia’s invasion, agriculture contributed to approximately 10% of Ukraine’s GDP and provided 41% of Ukraine’s export revenue, funds which are indispensable in their fight against the largest military attack in Europe since WWII. Ukraine’s GDP contracted by more than 29% in 2022 compared to 2021, and the contribution of agriculture to Ukraine’s GDP was 39% lower in 2022 than 2021, according to World Bank data. Russia’s occupation forced Ukraine to seek alternate routes for its exports, pushing up land transportation costs, while road and rail infrastructure was not equipped to handle the volume of grains Ukraine had shipped by sea.

In the past year, Ukraine’s riverine ports such as Izmail have seen a substantial increase in the volume of shipping that they have handled. While not sufficient to completely offset the impact of a blockade, this could substantially mitigate the challenge. Unsurprisingly, these ports have come under sustained air attack by Russia, and we should expect these physical attacks to be accompanied by cyber warfare on connected infrastructure in neighboring countries. At this point, we should expect further Russian retaliation against countries that have supported Ukraine and should look back to both NotPetya and WannaCry incidents – the first of which originated in Russia. The NotPetya attack of 2017 was first targeted at Ukrainian shipping and logistics companies, and the US government estimated the global costs inflicted by the attack to be more than $10 billion. Whether Russian hackers lost control of those attacks or were simply indifferent to the collateral damage they wreaked, the effects spread well beyond the immediate Ukrainian targets. The same risk remains this time, but with Romania as a primary target, followed by Croatia, Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, and other EU countries, facilitating the movements of Ukrainian grains.

The current global availability of foodstuffs does not mean all food security issues are over, as some Middle Eastern and African nations depend on affordable Ukrainian grain. The war will keep affecting Ukraine’s grain exports, and some of the largest importers in the most vulnerable countries will be forced to spend extra on the very basic foodstuffs their populations depend on. Since the war is unlikely to conclude soon – and the grain deal will likely not return – Ukrainian farmers will work less land next year, which, combined with the drought in southern Ukraine, following the destruction of the Kakhovka dam, will no doubt send prices soaring again. Pakistan, for example, is at risk of severe food deficiency in following months of drought with intense rainfall hitting the scorched earth in the aftermath. India, which proclaimed ambitions of becoming the bread-basket of the region just a short time ago is now moving to restrict food exports in order to avoid skyrocketing food prices plaguing the instability-ridden neighboring Pakistan. Amidst this crisis, Pakistan is attempting to displace almost two million Afghans it has been hosting on its territory, which could set another political crisis in motion.

Furthermore, analysts warn that food insecurity might spark increases in sectarian violence in Africa, the Middle East and parts of Asia, which would further degrade already poor relations among countries in the region. Any potential food insecurity could exacerbate the current strife relating to the ongoing war between Hamas and Israel, on which we have reported here. Further potential fallout in cyberspace would then be inevitable. What is likely to ensue is a Russian campaign which will see the employment of new weapons, new tactics as well as age-old tools of the cyber trade. This campaign has the potential to shape the outcome for millions of people in vulnerable food-importing countries around the world.

The logistics industry, being a critical part of infrastructure, confronts substantial risks from advanced threat actors. Data we have recently published on the industry reveals a consistent pattern of attacks, with a clear emphasis on developed economies and major global logistics hubs. Although true that the detection of APT campaigns has declined, a correlation between the current geopolitical landscape and the most targeted countries remains evident. Moreover, Russia seems to be increasingly employing privateering actors, motivated by financial gains to put distance between Moscow and the global food insecurity. Such a trend is expected to continue as privateers are offered ever more leniency: in the eyes of the Kremlin, the more global instability, the better the attention is deflected from its persecution of Ukraine, with fewer resources available to oppose it.