CYFIRMA’s intelligence indicates that the Iranian-backed Houtis are likely to – or at least attempt to – target the subsea cables that transport almost all of the data and financial communications between Europe and Asia.

So far, Houthi campaigns have disrupted energy supplies and commercial shipping through the choke point between the Indian Ocean and the Suez Canal, however, this new concern highlights how subsea infrastructure and its possible vulnerabilities are becoming more important in the context of global security.

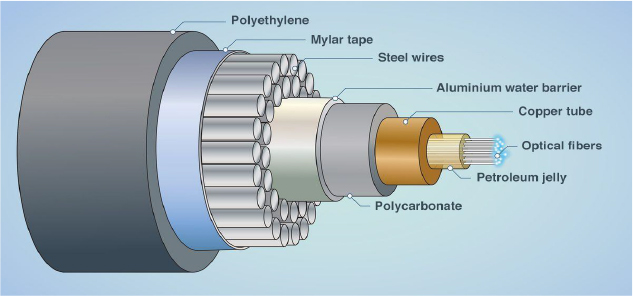

This term refers to the entire subsea network, including power cables, gas pipelines, and optic data cables that carry almost all intercontinental internet traffic (reportedly 97-99%, including banking transactions. It is estimated that there are currently over 500 active and scheduled submarine internet cables in the world: some may be relatively short (around 100 km) with the longest stretching up to 20,000 km. These ‘internet arteries‘ lie on the seabed, and can only be accessed by submarines. In shallower waters near the coast, however, they can theoretically be reached by a skilled diver or a ship’s anchor.

On average, there are more than a hundred submarine cable disruptions a year (usually the threats they face are not malicious: seabed erosion can damage them, as do storms, volcanic activity, and time). Submarine cables have a minimum lifespan of 25 years, and they generally face technological obsolescence before environmental destruction. Recently some companies have been trying to retrieve retired cable for recycling.

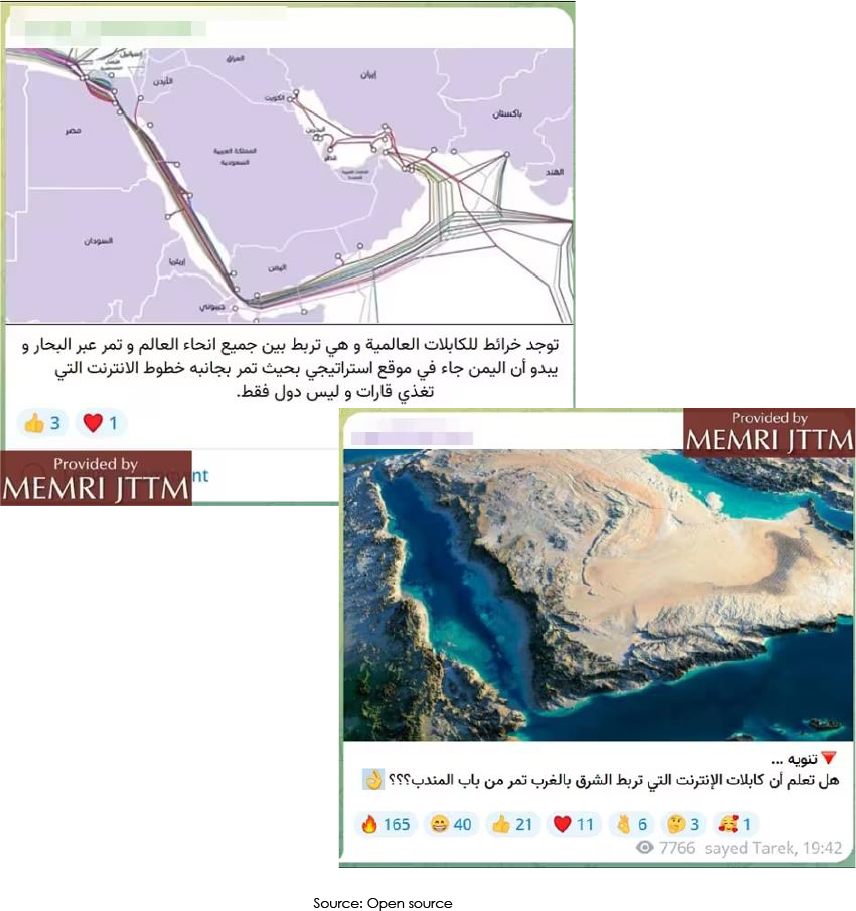

In late December, a Houthi-linked Telegram account posted what appeared to be threats against the fiber-optic cables that squeeze through the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, west of Yemen. These were echoed by accounts linked to other Iran-backed militants, including Hezbollah, who reportedly announced that “the global internet cables which pass through the Bab-el-Mandeb strait are in our grip”.

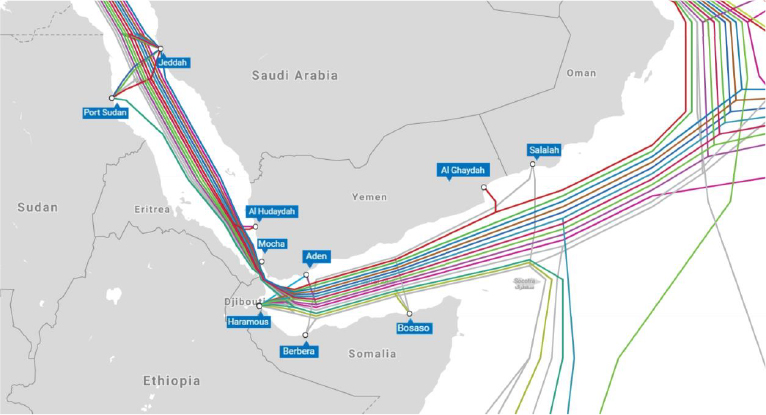

The Bab-el-Mandeb, or ‚Gate of Grief‘ is a strait between Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula and Djibouti and Eritrea in the Horn of Africa that connects the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden (and by extension, the Indian Ocean). Many analysts dismissed the threat as the Houthis were not thought to possess technological means, but a few weeks later – in the area where the Houthis operate – several undersea data cables were apparently severed. This episode was a dramatic reminder of how important data connectivity is in today’s world, and how little it takes to disrupt it.

What we know for certain thus far, is that there have been regional internet outages. An initial statement from internet operator Seacom was cautious: “The location of the cable break is significant due to its geopolitical sensitivity and ongoing tensions, making it a challenging environment for maintenance and repair,” the company said. It added, though, that there was no complete break anywhere. The Israeli press speculated that four submarine cables may have been severed; the AAE-1, Seacom, EIG and TGN – all of which pass through the area where the Houtis operate. While finding the undersea cable anywhere would be extremely challenging without detailed knowledge and technical equipment, this particular location is relatively convenient for a potential attack, as the Bab-el-Mandeb strait is only 25 km across, and hosts 15 undersea cables.

It is not easy to cut a submarine cable, and, because laying such a cable is extremely costly, the operators have devised a multitude of ways to safeguard them. In addition to the physical and financial expense to manufacture, there is also the economical and political value of the data they transmit – indeed, a single cable can carry several terabits per second, approximately a thousand times more than a satellite(with markedly fewer delays).

The rumored cable disruption occurred less than a month after the threats, however, the Houthis officially deny that they were responsible (whereas, they have claimed liability for naval attacks through the strait). Conversely, the Yemeni government – which battles the Houthis for control of their country – feels that it remains a possibility.

Sheer logistics supports the Houthi’s assertion that they were not to blame. Even if they had the support of Iran, the cables lie at depths greater than 150 meters (the average depth of the strait is 186 meters) and Iran so far has not demonstrated the ability to execute precise operations at those depts.

That said, Iran has exceeded international expectations previously, hacking into US drones, forcing them to land in Iran, reverse-engineering them, and then putting them into production. The same goes for cyber-enabled IP theft: Iran has produced parts that enable them to keep their pre-revolution, US-supplied planes in flight without an official supply of parts, or cooperation of the manufacturers.

As outlined in our recent report, Iran also appears to have judged the Houthis’ experiment in the Red Sea to be so successful that it bears repeating in the Mediterranean and elsewhere. “They shall soon await the closure of the Mediterranean Sea, [the Strait of] Gibraltar, and other waterways,” announced Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps on December 23rd, 2023.

Since Iran does not possess kinetic strike capability to hit targets at that distance, we can assume Iran’s cyber capabilities are being referred to, as well as the regime’s apparent willingness to use them.

In addition to natural phenomena, cables suffer the most from fishing trawlers, commercial vessels, or boat anchors (with around 150 incidents per year according to the International Cable Protection Committee), indeed, some contend that this presents a means for the Houthis to execute cable damage.

Simple attacks by non-state actors (such as a 2013 attempt by 3 divers to cut the SEA-ME-WE 4 submarine cable off the coast of Alexandria, Egypt) can create short-term, costly disruptions, but they are far more likely to take place closer to shore, where the damage is more readily repaired (for example the 2022 on-shore cable sabotage in Marseille, France).

Theoretically, a ‘gray zone operation’ of an organization or state could also be considered, a phrase that refers to situations where governments take anonymous, damaging actions that fall below the threshold of direct military action. Such activities may be deliberately disguised, or even portrayed as accidents or actions by independent groups. Political objectives may be served by the deployment of fishing vessels, while intentional security breaches may be passed off as mishaps. Because of this, there is a great deal of ambiguity and doubt regarding the actual nature and cause of the incident, which makes it challenging to evaluate the issue and respond appropriately.

Most analysts believe that the more likely explanation is that the damage to the cables was accidental; collateral caused by Houthi attacks on the British merchant ship ‘Rubymar‘.

Following the Houthi strike, the ship’s crew attempted to limit the vessel‘s uncontrolled movement across the sea by dropping anchor. This only partially worked, with the ship drifting anchor-down through the Red Sea for several days: given how densely the narrow Red Sea is crisscrossed with cables, the likelihood of the anchor hitting a cable is high, even if that wasn’t the Houthi’s intention.

Natural phenomena as a cause have been all but ruled out, as there were no storms, earthquakes, or underwater volcanic eruptions – all of which are the most common natural causes of submarine cable damage. Erosion, on the other hand, typically doesn’t cause multiple disturbances in such quick succession.

The short answer is No. Even in a situation of total cable destruction in the Red Sea, Europe or Asia has enough collateral connectivity to maintain a connection (as with naval traffic). Latency would increase by a few milliseconds – which is not a problematic delay for most services – but reliance on backup capacities is never ideal in the long run.

The internet has evolved from being pictures, videos, and text: it now hosts business data, financial transactions, and economic and military communications from every global nation. As such, these cables are “arteries of globalization”, and until recently, this area was dominated by South Asian manufacturers who took advantage of their region’s growing economies with increasing demand for connectivity.

In recent years, the US has become increasingly aware of this fact and is arguably becoming nervous about the extent to which the undersea communication industry is controlled by China. Many countries now have to “choose” sides – or worse, they may find that they have already inadvertently chosen as a result of previous decisions.

Last year, the Taiwanese island of Matsu lost its internet connection due to a Chinese ship that severed two internet cables, allegedly by mistake. The island, which has a population of 13,000, did not have reliable internet access for approximately 50 days, an “accidental blockade” that lasted so long because (among other reasons) Taiwan did not have its own cable repair ships. It was a potent lesson in the importance of having an alternative solution in the prospect of an internet outage, and sparked a discussion about the country’s communications‘ resilience, especially in the face of security threats from China.

Naturally, some argue that the accident on Matsu was a deliberate act, a test of what it looks like in practice when a region is cut off from the internet. In the event of a military conflict – such as a Chinese invasion of Taiwan – an internet blockade could be a highly effective weapon of control: Taiwan is no doubt now aware of this, and is reportedly working on a satellite replacement.

The US government – despite allowing the bulk collection of data unrelated to US citizens – often intervenes to prevent Chinese firms from competing to lay cables to the US. Big tech firms are also newly entering the game: in less than a decade, Microsoft, Alphabet (Google’s parent company), Meta (formerly Facebook) and Amazon have become dominant users of undersea cable capacity. Before 2012, their share of global undersea fiber-optic capacity was less than 10%, but today, it’s around 66% (most agree that soon they will be major players in the industry).

Weaponizing the seafloor is not entirely novel: The British cut German submarine telegraph cables at the start of World War I, and seabed sonar in the Greenland-Iceland-U.K. gap became a fixture in the Cold War, but the growing importance of subsea infrastructure to the global economy is forcing a rethink of the traditional naval mission of protecting sea lines of communication.

The bigger issue facing defense planners and security analysts is the growing realization of the importance and vulnerability of this huge subsea infrastructure. Oil and gas pipelines have proliferated, and subsea data links have grown exponentially in recent years and are poised for yet more spectacular growth this to keep up with the demand for digital transmission.

Submarine cables are information highways, tools for profit, and a means of geopolitical influence. It is rumored that scientists are devising a new type of cable (the so-called‘SMART‘ cable) that would produce data as well as transmit it. Such cables could measure crucial data – for example, to provide early warnings of volcanic eruptions or tsunamis – and have the capacity to recognize if and where it has been broken.

That’s a dream of tomorrow, however, as currently there are approximately 1.4 million kilometers of cables under the seabed, so it will be a long time before even a percentage of that is replaced. The battle over who will lay the next generation of invisible digital highways has already begun, and despite the nascent competition from satellite mega conglomerations, the sheer volume of cables means their market share is not going to drop dramatically anytime soon.

Besides physical threats, there’s always the risk of cyber or network attacks. By hacking into the network management systems that private companies use to manage data traffic passing through the cables, malicious actors could disrupt data flows. A “nightmare scenario” would involve a hacker gaining control, or administrative rights, of a network management system: at that point, physical vulnerabilities could be discovered, disrupting or diverting data traffic, or even executing a “kill click” (deleting the wavelengths used to transmit data). The potential for sabotage or espionage is quite clear – and according to reports, the security of many of the network management systems is not up to date. The well-publicized attacks on critical infrastructure like SolarWinds and Colonial Pipeline cyberattacks also exposed the cyber vulnerabilities of the U.S. private sector with dramatic implications for national security.

In an effort to reduce costs, streamline operations, and enhance performance, submarine cable owners and operators are increasingly turning to remote network management systems to monitor and control their infrastructure. Since these systems nearly always need to be connected to the internet, they are vulnerable to ransomware organizations, hacktivists, state-sponsored adversaries, and other cyber threat actors. Pursuing expediency may then come at a very high cost since the security and resilience of the entire cable system are increasingly at risk from third-party vulnerabilities. A peek into that potential future occurred in April 2022 when U.S. federal agents stopped a cyberattack against a Hawaii undersea cable operating system, which was made possible by a third-party credential leak.

The 2020 breach of SolarWinds’ Orion platform and the 2021 breach of Kaseya’s Virtual Systems Administrator product are two significant cyberattacks that have recently taken advantage of flaws in remote management systems or comparable products. These attacks draw attention to the dangers of using third parties, particularly when the affected goods have privileged access to consumer networks.

Although their threat cannot be dismissed, non-state actors will probably be less likely and less capable of causing harm to the networks and operating systems that submarine cables depend on. Accidental damage caused by fishing boats or ship anchors will continue to be a hazard, however, the physical infrastructure is always at risk from highly capable state-sponsored actors – and the same goes for the cyber threat to the management systems.