With Donald Trump’s erratic style and his many isolationist tendencies, none of America’s allies can be 100% sure where they stand. Unlike Ukraine—which, despite America’s wavering, still maintains the support of European nations—Taiwan cannot rely on a similar level of backing from its Asian neighbors.

Deterring China from invading Taiwan primarily depends on the U.S. commitment to help defend it. However, tariffs on Taiwan and American allies, combined with the constant threat of abandoning Ukraine in desperate times, have significantly eroded the credibility of potential U.S. support.

The Trump administration shows very little regard for diplomatic conventions and U.S. commitments. From Beijing’s perspective, the U.S. now seems inward-looking, and in the next four years, it likely wouldn’t come to Taiwan’s aid. This creates a critical window of opportunity for the Chinese leader, who has spent years building military capabilities for operations across the Taiwan Strait.

In recent weeks, Taiwan has sharply criticized China for conducting live-fire military drills off the island’s southwestern coast without prior warning. This is just one of Beijing’s countless provocations and came only days after similar Chinese behavior between Australia and New Zealand, much to the dismay of both governments.

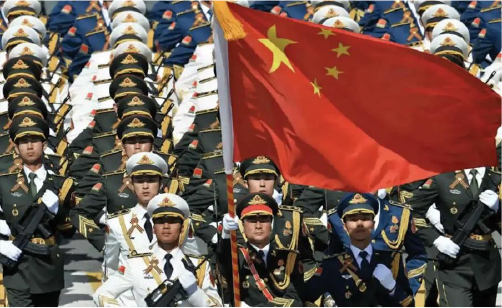

In early April, China conducted its “Thunder in the Strait 2025” military exercises, simulating a blockade and missile and air strikes against Taiwan’s northern, southern, and eastern coasts. Beijing asserted these drills were a direct response to “provocations” by Taiwanese President Lai, whom it labeled a “parasite” for advocating independence. This came after President Lai’s mid-March speech, where he described mainland China as a “foreign hostile force” and unveiled over a dozen new measures to counter Chinese influence.

This heightened aggression suggests China is increasingly prepared to achieve its strategic goals through force, rather than cultivating an image as a reliable global partner, especially given the political divisions in the United States under Donald Trump.

In recent weeks, reports have emerged indicating that Chinese shipyards are constructing a fleet of vessels specifically tailored for a potential invasion of Taiwan. Years earlier, Xi Jinping had directed the military to develop a viable option for such an operation by 2027.

China’s capacity to transport troops by sea has long been a critical limitation on its ability to mount an invasion. Until recently, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) lacked the logistical infrastructure to support such an operation. However, under Xi Jinping’s “civil-military fusion” strategy, civilian shipyards are now mandated to construct ferries to military specifications—enabling their immediate requisition in the event of conflict.

These ships are also organized into the maritime militia and regularly practice amphibious landings. The report on the invasion fleet construction comes shortly after it was revealed that China is building a massive wartime command facility near Beijing. Once completed, this nuclear bunker will be the largest military command center in the world—spanning over five square kilometers—at least ten times the size of the Pentagon.

According to the CIA, the construction of a modern underground military command bunker—set to include Xi Jinping in his role as chairman of the Central Military Commission—reflects Beijing’s ambition to develop not only elite conventional forces but also advanced nuclear warfare capabilities. This intent is further highlighted by the Chinese Communist Party’s substantial investments in modernizing and expanding the country’s nuclear arsenal. Shortly after these developments, the Chinese embassy in the U.S. declared that China is prepared to “fight the U.S. in any war to the end.” The statement followed an announcement by Premier Li Qiang (not to be confused with former Premier Li Keqiang, who was ousted by Xi and later died under unclear circumstances) that China’s official defense budget would increase by over 7%. Li also invoked a familiar phrase in Chinese political rhetoric: “Changes unseen in a century are accelerating worldwide”—a reference to China’s strategic goal of displacing the United States as the dominant global power.

China has also built a mock-up of key areas of the Taiwanese capital Taipei—including the presidential palace and other government buildings—at a desert training site. This continues from an older mock-up of the Taiwanese presidential palace in Inner Mongolia, where satellite images show the Chinese army has been training for a decade. In the desert, China is also constructing mock-ups of U.S. aircraft carriers to test its ballistic missiles.

In late 2023, the U.S. Department of Defense released its annual 182-page report on China’s military—a requirement under Congressional mandate since 2000. Widely regarded as the most comprehensive public assessment of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the report is a key resource for analysts tracking the evolution of China’s military power, despite containing a classified annex.

This year’s edition significantly revised the estimated true size of China’s defense budget upward —already the world’s second, largest after that of the United States—to between 1.5 and 2 times its official figure, placing it in the range of $330–450 billion. Adjusted for purchasing power parity, that brings China’s military spending close to the U.S. defense budget of approximately $850 billion.

The following summary highlights several key findings from this year’s report:

Beijing appears to be transitioning its economy towards a wartime footing. Over the past decade, the Communist Party has ramped up defense production and heavily invested in the research, development, and manufacturing of advanced weapons systems—with significant success.

China’s defense industry efforts have greatly strengthened its military capabilities. The PLA has an impressive arsenal of precision-guided medium and long-range missiles capable of targeting most U.S. and allied bases in the Indo-Pacific. It is also developing a robust air defense network to restrict U.S. force mobility in the region. Three of the world’s ten largest defense companies are now Chinese: AVIC, NORINCO, and China South Industries Group.

China is also by far the world’s largest shipbuilder, with an annual capacity to build 23 million tons of displacement compared to under 100,000 tons in the U.S. One Chinese shipyard, Jiangnan on Changxing Island, is estimated by the U.S. Navy to have more capacity than all American shipyards combined.

Over the past two decades, China has absorbed massive quantities of raw materials to support its growing and wealthier population’s demand for food, energy, and industrial output. Despite recent economic woes and a real estate crisis, China continues building new industries and transitioning away from resource-heavy sectors. Logically, commodity demand should be declining.

But the opposite is happening. Last year, Chinese imports of many key inputs hit record highs, with total commodity imports rising 16% by volume—and an additional 6% in the first months of this year. This doesn’t reflect growing consumption amid economic woes, but rather rapid stockpiling of resources—at a time when commodities are expensive.

Unlike Russia, China is heavily dependent on foreign imports. It may be a global refining center for many metals, but it imports most raw materials—70% of the bauxite for aluminum, and 97% of cobalt. It also relies on imported energy. While it has large coal reserves, it must import 40% of its natural gas and 70% of its oil. Its most acute dependency, however, is food. In 2000, nearly everything Chinese people ate was domestically produced; today, it’s less than two-thirds. It imports 85% of its 125 million tons of annual soybeans to feed 400 million pigs. Its reliance on foreign coffee, palm oil, and dairy is nearly total.

China seems to be preparing for a hostile international environment. This begins with expanding its storage infrastructure. Between 2010 and 2020, underground gas storage capacity rose sixfold to 15 billion cubic meters (bcm); the goal is 55 bcm by next year. China is also building a dozen LNG storage tanks along its coast. JPMorgan Chase estimates storage will reach 85 bcm by 2030.

China is also actively filling these facilities. In another sign of war preparations, state statisticians have stopped publishing many commodity reserve figures. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that by the end of the current growing season, China will hold 51% of the world’s wheat and 67% of its corn reserves—enough for at least a year of demand. Soybean reserves, China’s biggest agricultural import, have doubled since 2018 to 39 million tons and are expected to reach 42 million tons by season’s end.

Even more significant is China’s stockpiling of metals and fuels. Estimated reserves of copper, nickel, and other metals could cover between 35% and 133% of annual demand, depending on the commodity.

Xi Jinping declared that China must prepare for “the worst and most extreme scenarios” and be ready to face “strong winds, turbulent waters, and even dangerous storms”, as the party seeks to reduce the vulnerability of its economy to potential Western sanctions. As U.S. Secretary of the Air Force, Frank Kendall recently remarked in response, intelligence could not be clearer: China is preparing for war—specifically, a war with the United States.

China is a global champion in using cyber attacks as a tool of statecraft, and the hands-on role of the government in the economy only reinforces the drive to use cyber attacks for IP theft, even in matters that are of no military or dual use. China has a bigger hacking program than that of every other major nation combined, and any large company in industries outlined in Chinese development plans will need to invest in external threat landscape management solutions to stay ahead of relentless and repeated assaults by Chinese hackers. China is also trying to push into cracks in Western critical infrastructure.

Case in point, according to fresh media reports, in a closed-door meeting last December in Geneva, Switzerland, Chinese officials privately acknowledged that Beijing was behind a series of aggressive cyberattacks targeting U.S. critical infrastructure.

Chinese officials, in veiled comments, linked years of cyberattacks on U.S. ports, water systems, airports, and other sectors to Washington’s support for Taiwan. Previously denied and blamed on criminals, these intrusions—now tied to the Volt Typhoon group—were tacitly acknowledged during the meeting, serving as an implicit warning over Taiwan.

Since the Geneva meeting, U.S.-China relations have worsened due to an escalating trade war, suggesting a likely surge in similar cyber activity. Top Trump administration officials have pledged to increase offensive cyber operations against China. Meanwhile, Beijing continues to leverage access to U.S. telecommunications systems from a separate breach linked to a group called Salt Typhoon.

This escalation in tensions means the ongoing trade war is spilling into digital realms, heightening the risk of cyberattacks.

Some organizations might be facing hard budgetary choices with some managers preferring to cut cybersecurity first. That would be a critical mistake, as many more cyberattacks typically occur during economic downturns and we are moving into a more chaotic geopolitical environment, where predatory states like China, Iran, or North Korea will use the resources of the state to aid their flailing business. Security should be viewed as vital for continuity and competitiveness and cutting cyber security budgets in a volatile environment (both economically and geopolitically) would be a mistake. China is already running a massive-scale state-backed IP theft programme, which is part of a much larger industrial strategy that China uses to displace companies from competitor countries. Any geopolitical strains will incentivise Beijing to focus more resources on its cyberespionage. But that’s not the full extent of it.

Compounding concerns, the U.S. administration recently announced sweeping layoffs of cybersecurity personnel and dismissed both the director and deputy director of the National Security Agency. These moves have raised alarms among intelligence officials and lawmakers about weakening national defenses at a critical time.

China’s targeting of civilian infrastructure represents one of the most serious threats currently facing the Trump administration, which is not paying enough attention to it; with the situation in many other nations being also dissatisfactory due to already existing budgetary pressures, further exacerbated by Trump’s trade war.

Meanwhile, China is increasingly embedding itself within U.S. critical infrastructure through sophisticated cyber intrusions, aiming to establish covert access points that could be leveraged in the event of a conflict over Taiwan. U.S. intelligence and cybersecurity officials have warned that Chinese state-sponsored hackers have infiltrated systems controlling power grids, communications networks, transportation hubs, and water treatment facilities. Unlike traditional cyber espionage focused on data theft, these operations are designed for persistence and potential disruption. The objective appears to be the creation of digital “sleeper cells” capable of sabotaging key infrastructure to sow chaos, delay military mobilization, and undermine public confidence during a crisis. This strategy reflects a broader Chinese doctrine that views cyber capabilities as a critical component of asymmetric warfare—especially against technologically advanced adversaries like the United States.

Many U.S. officials concur, with former CIA Director William Burns noting China’s aim to control Taiwan, or at least develop the capability, by 2027. Amidst a slowing economy and demographic decline, many analysts believe China might act aggressively to divert from domestic issues or solidify international gains while still at its peak influence.

We now know that although Europe was prepared for war in 1914, World War 1 might not have happened if the driver of the car carrying Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand hadn’t made what is likely the most fateful wrong turn in history. Wars often resemble earthquakes—we may not know exactly when they will strike, but we can recognize the factors that increase or decrease the level of risk. And today, China’s risk indicators are flashing a warning red.

A major failure by the Chinese military—for example, in an attempt to seize Taiwan—would almost certainly trigger a prolonged war in the heart of the Indo-Pacific. This would inevitably severely disrupt regional maritime routes, air traffic, and supply chains. As a result, a prolonged conflict over Taiwan would be far more devastating than the ongoing war in Ukraine, both regionally and globally, with estimated costs amounting to 10% of global GDP.